Ibadan. Ibadan University Press. 1986. 48 p.

The desire to beautify one's body, which man acquires early in life, is not less keen in the Fulani nomads, despite their hard and unsettled mode of life. That they pay much attention to their personal appearance is evident not only in the ways they bedeck their bodies, but also from the mirror which is sewn into a leather wallet (by Hausa leather workers in Nigeria), is always hung like a jewel from round their necks on their chests so that they can check up on their appearance from time to time. It is used by both men and women in their adolescence and early manhood.

This desire for personal ornamentation or beautification is, among the Nigerian Fulani nomads, satisfied and fulfilled mainly in their coiffure, body markings and the use of jewellery. Body painting which is purported to be used by the Fulani in general during important festivities such as geerewol 1, their songs and dance display or sharo, their male youths' test of endurance, if the latter is ever applicable to the Fulani nomads in Nigeria, seems to have been discontinued. Their women, however, colour their feet and hands with henna like the women of other ethnic groups in Nigeria. The elaborate dress which their sedentary neighbours living in urban centres take pride in displaying in various styles and materials also seem not to be of much use to them as aids to body adornment; being too cumbersome for their nomadic life.

The Nigerian Fulani nomads are satisfied with the readily available, cheap, locally made, or imported clothes made into traditionally Fulani nomads' styles by their settled tailors. Their wardrobes are usually limited to one or two outf its that are used for special occasions and a single day-to-day outf it of a simple material and style.

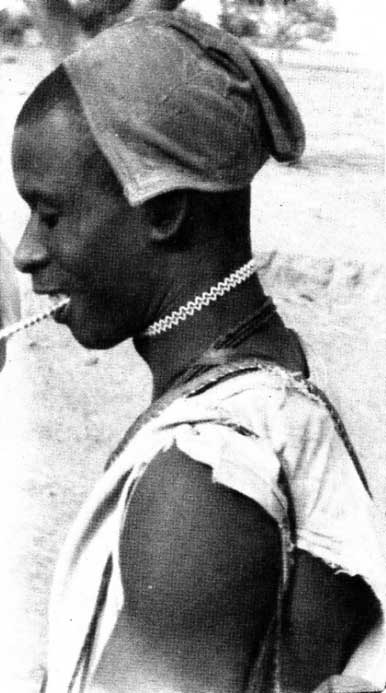

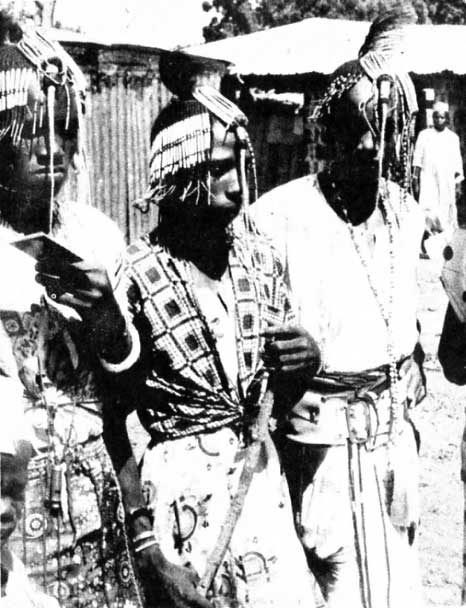

Plate 2. A young Fulani man of Gusau… |

Plate 3. …Idem.The close haircut indicates a newly married state. |

Their men's outfit consists of simple jumpers and tight-fitting knickerbockers (Plates 2 & 3 above) The jumpers have round necks, flared bottoms and are either sleeveless with open sides (hausa: yar ciki) or with sleeves that reach just beyond the elbow but are sewn up at the sides. Both their garments and knickerbockers are adorned with simple embroidery. Spiralled stitches surround the round necks of the garments, and leaving some gap after the neck seams, are courses of square stitches with two diagnoally opposing angles of the square resting on the shoulders and the other two pointing downwards on the chest and the back. Few other abstract patterns may be added to the chest and the back. The knickerbockers only have courses of stitches round the opening of their legs.

Women generally tie a cloth round their bodies from below the arm pits and above the breasts to the calves; a smaller piece is tied around the waist and is used as a shawl. Their maidens tie a wrapper at the waist, but wear blouses or sleeveless bodices which hardly cover their bosoms.

At present, industrial clothes are used for most of their dresses but, in the past, their dresses were made from locally made materials which are still used by some of them in certain places. As I said earlier, those in Hausaland still make use of the indigenous materials of predominantly white colour while those living in Nupeland use the indigenous scarlet materials of the Nupe. In northeastern Nigeria down to the Cameroons, their women are seen in materials of deep blue to purely black colours which are also highly prized traditionally by the Kanuri.

Basically, to the Fulani nomads, clothes are to conceal their nudity and to some extent to protect their bodies from the elements. The choice of materials and styles which make clothing assume an ornamental role to the body is obviously mute among them. Neither is the prestige aspect of cloth wearing of much interest to them. At times they buy their ready-made garments without much regard for fitting, thus their garments appear looser than those of their sedentary neighbours.

The care of the hair, on the other hand, is the only aspect of personal adornment in which they are self-sufficient and to which they pay much attention. “The only raw material giving rise to the actual execution of an artistic style by Fulani hands is hair”, observes Delange 2. She further notes that their hairstyles are so elaborate that specific patterns in Lower Senegal bear specific names while some in Futa-Djallon remind one of Calder's mobiles 3. Hairstyle, which is basically a type of personal adornment, is thus elevated to the level of pure art.

In Nigeria, the hair-styles of the Fulani nomads are not less elaborate or artistic, but much depends on the locality, sex, age and social status of individual weavers than those of Fulani nomads elsewhere 4.

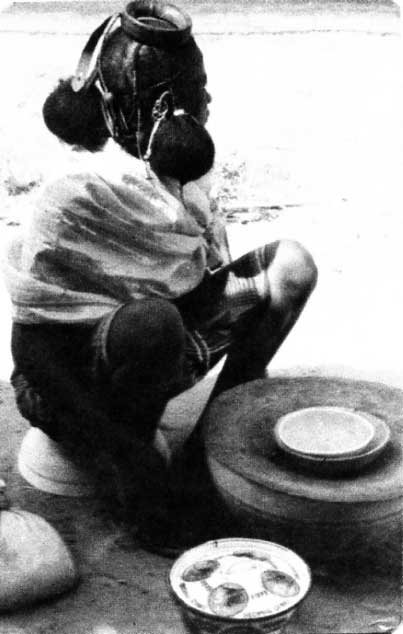

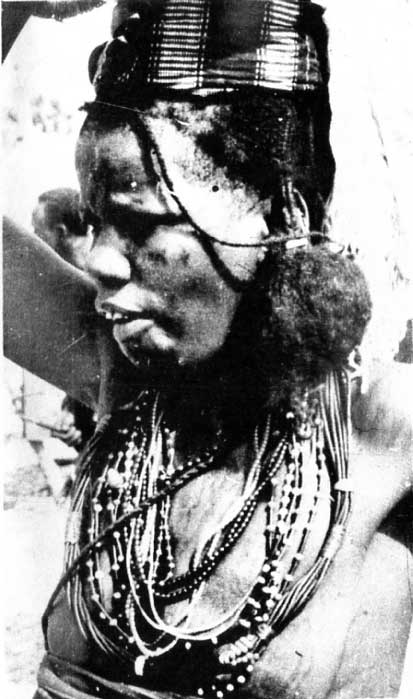

However, the nomadic Fulani women in Nigeria have preference for designs which are convenient for their dairy hawking and other housebold activities wh ich involve carrying loads on the head. The characteristic aspect of their hair styles are therefore the braids that hang down the back and the sides of the face. In Kontagora area around 1978, it was fashionable for nomadic Fulani women to make such hangings into pendulous bulbs bung with simple thin braids and terminated with short ones (Plates 4 & 5).

In northeastern Nigeria, and in fact from Borno down to the Cameroons, nomadic Fulani women prefer to pack a substantial amount of their hair into the centre of the head like a flat bed stretching from the forehead to the back with hanging braids to the sides and the back.

In other parts of Nigeria, the female Fulani nomads use simple thick, hanging braids, usually one on each side of the face and a big one or some smaller ones at the back. The focus on the sides and back of the head in their hair styling is to ensure that the ornamental purpose for which the hair is done, is not defeated, as elaborate designs on top of the head will be covered by their usual headloads.

Similarly hanging braids, two falling on the cheeks, and ornamented with a white bead under the chin are reported to be worn by Fulani women of Dori who have just had their first baby, in other words, recently married, as Fulani women are not considered properly married until they have their first babies. The hanging braids together with the braids on the nape of her neck, which look like multiple fringes ornamented with stones, are said to symbolize wisdom and calmness, expedient of a new mother of a family 5. But such symbolic association does not seem to hold for such braids of Nigerian Fulani women. This is not to say that special hair styles are not made for that stage of life, the time for their proper marriage.

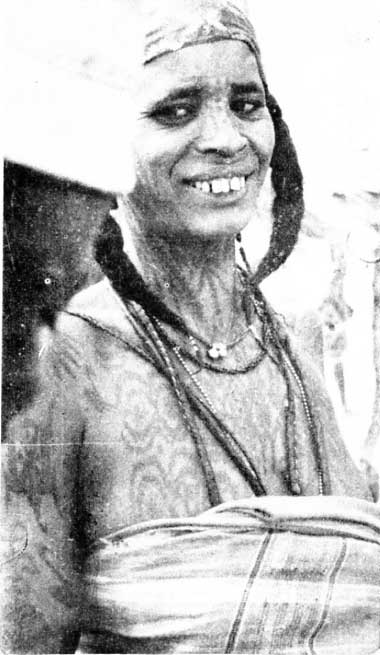

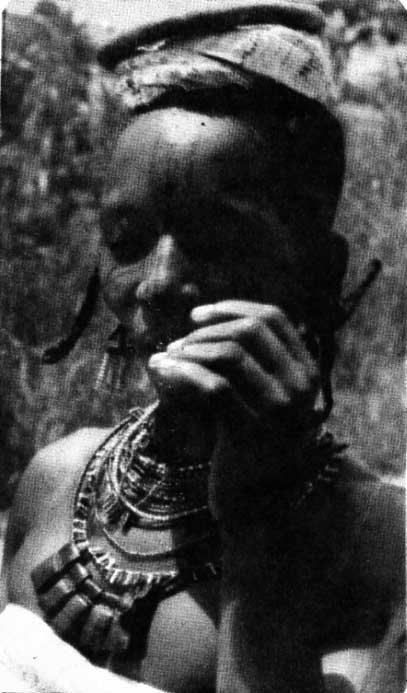

But in Nigeria styles similar to the one described above are adopted irrespective of the woments ages and number of children. Women who have apparently passed childbearing age also wear such styles (plate 6), to which most of them also add according to their different tastes, beads, buttons, cowrie shells and various pieces of bright metals, whose colours contrast sharply with their black hair.

The braids of the hair, too, are in most cases not the natural hair of the wearers. According to Eve de Negri, nomadic Fulani make use of false hair, which is generally believed to have been passed down from generation to generation 6. The false hair is said to be intertwined with the wearer's own hair to give the long braids. However, in many cases, the braids are not attached to the natural hair, but made into wig forms attached to round strings with which they are worn or tied to the head (plate 4). The false hair is used to make up for the shortness common with the hair of Fulani women. Dupire, commenting on the short hair of the Woɗaaɓe women in Niger says, “Leurs cheveux étant ordinairement courts et crépus, les femmes wodaabe envient la chevelure plus longue et plus souple, qui est l'apanage de quelques heureuses élues”. 7 [As their hair is usually short and kinky, Woɗaaɓe women envy the longer and softer hair which they consider a beautiful characteristic of luckier women.]

Except the beard which elderly men grow, which to them, like to other Nigerians such as the Afo 8 and the Yoruba 9 is a sign of old age, they invariably tonsure or keep their hair low after marriage (plate 4). Very early in life, male children are shaved clean leaving only a tuft of hair in the middle of the head, a style which they adopt until their puberty rite, habrekoogal, in which the hair is ceremonially shaved 10. In most parts of northern Nigeria, particularly in Hausa-speaking areas, most boys keep their hair low as from that ceremony, as the practice whereby they grow long hair made into elaborate styles which Eve de Negri rightly refers to as courting styles 11, seems to be dying out. In northeastern Nigeria, however, the practice is still alive.

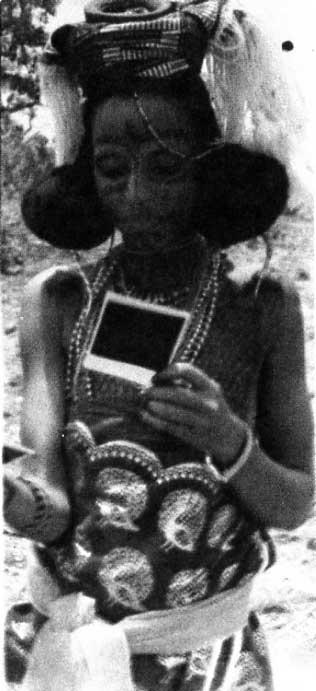

Examples of such styles worn by young nomads in Biu and Meringa on market days and during Muslim festivals are the most elaborate hair styles I have seen worn by the Fulani of Nigeria (plates 7 & 8). These boys do not usually carry anything on their heads as the Fulani women do, so the designs are spectacular at the sides, the back and top of the head and their principal braids covered by bits of metal arranged into heavy elaborate surfaces dangle as they freely hang over the face. Basically their hair is braided into numerous thin rows traditional to the Kanuri and on to a big tuft of hair left at the middle of the head are attached some pieces of metal. From the side of the tuft two or three oblong masses of hair covered with parallel rows of metal ornaments which project forward, hanging over the face at the front and left side. Pieces of metal ornaments are also worn onto the braids at the right side and back of the head which like mats cover the ear.

In their jeerewol, which I witnessed in Meringa in 1978, groups of young boys and girls dance in relay to different tunes (Plate 9). made their dances spectacular was not any special steps or body movements but the glitter and reflection caused by the head ornaments moving up and down in the bright sun, coupled with the billowing of the bottom of their long loose garments secured at the waist with belts ornamented also with some bright metal pieces. Perhaps, few people enjoyed the performance as much as the girls to whom the boys wanted to appear their best, but we all appeared enthralled.

Few general remarks are documented on body markings which, as I have said, are another important body adornment of the nomadic Fulani, and the limited literature tends to confuse rather than clarify the real significance of body marking patterns according to their ethnic or any other groupings.

The marks are group badges or emblems predetermined by all members of the group or their ancestors. It is with this notion that Meek, speaking on the use of body markings to distinguish membership of ethnic groups in Northern Nigeria as emanating from precaution against loss of identity during the days of slavery, says that the Jukun and the pure-bred Fulani have no such marks which to them are the hallmark of slavery 12. The view also underlies Reed's observation on the Daneeji and the Hontorbe Fulani groups of northeastern Nigeria of whom he observes:

To prove that they (the Hontorbe and Daneeji) are not Woɗaaɓe, they point to the fact that they have tribal face marks, whereas the Woɗaaɓe as a rule have none 13.

What Meek means by the “pure-bred” among the Fulani is relative, depending on individual Fulani informants while the differing marks of the Hontorbe and Daneeji as illustrated by Reed are variations of Hausa yan baki, in which the strokes of the patterns converge at the corners of the mouth. In its original scarification form, it used to be given to children who are believed to have been reborn after their previous infantile death, but now in its coloured tattoo forms are just facial ornaments adopted as a fad by many ethnic groups in northern Nigeria. That apart, the Woɗaaɓe who he says wear no face marks do wear face markings in Adamawa and their face marking which are in keloids are made up of their own version of yan baki, to which other patterns, are added on the temple and the forehead 14. Also common with the face markings of other Fulani nomad groups like Daneeji and Jafun in the area is the corner-of-the-mouth marks 15.

The type of marking appears to depend on their localities, groups with whom they share fashion, as well as individuals. For example, most of the patterns worn by the Fulani nomads in northeastern Nigeria, as I have said in respect of the Woɗaaɓe of Adamawa are in keloids which are due to the absence of specialist markers, evident from the fact that the Fulani women in the area are often seen on market days helping one another to make the marks. On the other hand, in Hausaland where the nomadic Fulani depend on Hausa tattooers, yan jarfa, the markings are coloured fine lines and not in keloids.

The area where the Fulani nomads appear mostly to share body marking fashion with their sedentary neighbours and where their markings still very much depend on the taste of individual wearers is Kontagora and Yauri areas where the Hausa yan jarfa are asked by various ethnic groups to cover almost every part of their bodies with various figural as well as abstract motifs (Plates 5 & 6). While the woman on Plate 5 has her face, chest and the arm covered with images of trees, birds and animals, the woman in Plate 6 in addition to some marks which parody her eyebrows on the forehead, and some other marks below the eyes and at the corner of the mouth, has her neck and chest decorated with latticed patterns which cover her like a turtle-neck apron. How far the tattoo pattern goes down on the front part of the body is not known.

Most of the markings are purely ornamental and the designs are in most cases named after their positions on the face or the body 16. The marks are made when the wearer is old enough to decide for him or herself, and are unlike the scarification marks which among many Nigerian ethnic groups are made on the wearer when he or she is a child. Their mark patterns become associated with certain groups only because people in the same group and in the same localities tend to follow the same fashion.

Jewellery is another noticeable form of body ornamentation among the Fulani nomads of Nigeria, and the amount and the items they use like their coiffure and and body markings vary according to place, the groups to which they belong or are associated, as well as their sex, age, and time. Men generally wear minimal jewels and only until their middle age. The women, however, put on jewels particularly chains of beads which at times are in quantities almost tantamount to the abuse of the items used (Plate 10). The various kinds of beads sold in the local markets have their ready buyers among their women. They string them according to their types and wear them together in abundance on the neck, not impossibly, for prestige sake.

This is not to say that they wear them regardless of aesthetic and ornamental consideration commonly basic to the use of jewels. Even charms or medicines made traditionally into leather tablets which are carried hidden under the dresses by most other Nigerians are worn openly by the Nomadic Fulani women, well arranged on the neck to go with their other neck jewelry (Plates 11a & 11b).

Plate 11a. A fulani woman from Bauchi her beads attachedto the head with string, her leather tablet charms arranged neatly around her neck. |

Plate 11b. Traditional Hausa tatoo patterns. |

Some of their jewels have some age-long value comparable to the values of akori or iyun and segi beads among the Edo or Yoruba respectively. In Kontagora area, two types of rare beads which are very expensive are much valued by the nomadic Fulani women. The first is the kanduji, which as I said in the introduction is worn by the Hausajin, a Fulani group considered by other Fulani groups as having deep knowledge of the Hausa language (Plate 1). They are a kind of big white bead, the material and origin of which could not be ascertained.

The second, maji, is also of unknown origin, but seems to me to be old demarcation beads of Islamic rosary as it is oblong in form, with the holes for the string made on the side instead of from top to bottom similar to such beads which usually divide the rosary into three equal numbers of beads (Places 12 & 13). Plate 12. Nomadic Fulani women of Kontagora area wearing maji neck beads. Plate 12. Nomadic Fulani women of Kontagora area wearing maji neck beads. |

Plate 13. Idem. |

The nomadic Fulani also display ornaments on their wrists and ears. In the past their women used to put on heavy metal bracelets which are now commonly discarded and being sold by dealers of odd things, at times, to metal workers who fashion them into something else. Nowadays, the predilection of the nomadic Fulani women is for lighter things which do not disturb their use of the hands. Bangles are not displayed on the legs but their men often wear them tight on their arms. The bangles are usually not mere ornaments but protective charms or amulets.

Generally speaking, the body ornaments of the nomadic Fulani are so distinctive that a Fulani nomad is not hard to distinguish anywhere among other Nigerians.

As they stay very little indoors, they are always seen fully bedecked by the items we have discussed. Their basic aim for appearing so is to look good to other Fulani nomads as well as other people and the ornaments cannot be totally separated from the desire for prestigious display of wealth. However, the situation whereby jewellery is invested in only to be sold later, particularly in difficult financial situations, common to some other Nigerian peoples, has not been ascertained to exist among the Fulani nomads.

Notes

1. Delange, 1974, p. 148 and Brain, 1980, p. 58.

2. Delange, 1974, pp. 142 & 143.

3. Delange, 1974, p. 143.

4. Delange, 1974 p. 143 and Brain, 1980, p. 57.

5. Brain, 1980, pp. 56 and 57.

6. Eve de Negri, Nigerian Body Adornment, Lagos: Nigeria Magazine, 1976, p, 15.

7. Ibid.

8. Marguerite Dupire, Peuls nomades: Etudes descriptive des Woɗaaɓe du Sahel nigerien, Paris: Institut d'Ethnologie, 1962, p. 6. [Nomadic Peuls: Descriptive studies of the Woɗaaɓe of the Niger Sahel.)

9. Elsy Leuzinger, “Die shnitz-kunst im Leben der Afo von Nordien-Nigeria”, Geographica Helvetica, Zurich and Bern, 17. 1966,,pp. 162-161.

10. Irungbon, the beard, is said by the Yoruba to be old age as contrasted with the moustache, tuborru, which is grown precociously and therefore makes the young not respect those who are older than they are.

11. Agency no K2055, a letter from the Resident, Sokoto Province to the Secretary, Northern Provinces 194/1926/29 of 9th July, 1927, p. 52.

12. Eve de Negri, 1976, p. 16.

13. C.K. Meek, ne Northern Tribes of Nigeria, vol. 1, London: O.U.P., 1921, Humphrey Milford, 1925, p. 44.

14. Reed, 1932, p. 426.

15. Chappel. 1977, photographs of Woɗaaɓe women wearing facial marks in plates 21-23.

16. Chappel, 1977, p. 203, showing a diagram of Pastoral Fulani scarifications.

17. Ibid. (explanatory notes to the diagrams).