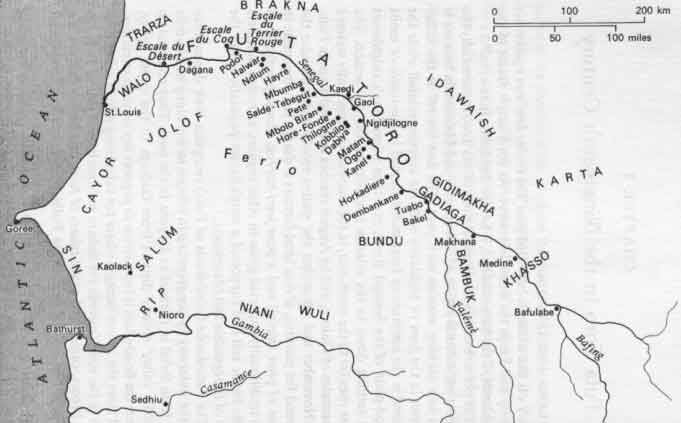

Map I. Futa Tooro and surrounding areas in the nineteenth century

Clarendon Press. Oxford. 1975. 239 pages

“Futa is like a double-barrelled gun. The owner fires one against his enemy and keeps the other in reserve. As for Futa, it farms in the highlands; if the harvest is bad, it has the floodplain in reserve.” 1

The proverb makes the essential point: Futa Tooro is potentially the richest agricultural region of Senegambia and Mauritania because it has two growing seasons each year. The first “barrel” is the millet grown in the jeeri or highlands with the summer rainfall while the second is the sorghum or large millet farmed in the waalo or moist flood-plain of the Senegal River, at a time when Futa's neighbours are settling down to the relative inactivity of the dry season. The river rises far to the south-east, in the much more abundantly watered mountains of Guinea, and by August reaches the flood stage in Futa. In November and December the waters recede and surrender the ground for planting, giving local farmers a chance to compensate in cases of poor rainfall and a poor jeeri harvest.

Consequently, Futa has traditionally exported grain to other regions, attracted outsiders to its fertile soil and supported a much denser population than the rest of Senegambia and Mauritania.

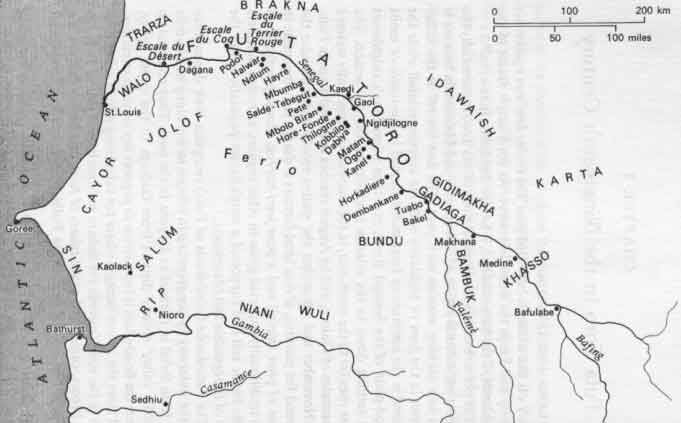

The Futankooɓe (inhabitants of Futa) recognize their dependence on the waterway by congregating in villages strung along its 240-mile arc from Bakel in the east to Dagana in the west. They constitute a “middle valley” society distinct from Gadiaga or the upper valley, where the flood-plain is too narrow to support dry season agriculture, and from the Lower Senegal where the tides bring a high saline content to the soil. Towards the Sahara or Mauritanian side of Futa are the Moors, camel- and cattle-raisers of Arab and Berber descent. To the south or Senegalese side are Fulɓe pastoralists in a semi-desert called the Ferlo 2. Both Moors and Fulɓe have customarily come to Futa during the dry season for food and water for themselves and their flocks. Given its long and slender shape and the pressures from nomadic neighbours, the middle valley has always been a particularly difficult area to rule.

Map I. Futa Tooro and surrounding areas in the nineteenth century

The “width” or north-south extent of Futa varies from ten to fifteen miles and breaks down into the main river channel, waalo or flood-plain on either side and jeeri or highlands just beyond that. The jeeri, in fact, is only a few feet above the waalo, just enough to escape the annual inundation, and fades off into wilderness and desert in both Mauritania and Senegal. The fields north of the river are just as fertile as those to the south, but most Futankooɓe have chosen to live on the Senegalese side since the period of intense Moorish raiding in the eighteenth century. Their villages are located primarily in the southern jeeri to avoid the high water, but some important centres are found on elevated land beside the main channel.

In contrast to the jeeri, where land had little scarcity value and belonged to whoever cleared and cultivated it, the much-coveted flood-plain has long been subject to complicated rules which survive today 3. They recognized two kinds of claim: the right of cultivation and the right of ownership. The “master of fire” was the family which first cleared the land and retained the right to farm it under normal circumstances.

Superimposed upon this claim was the right to tax vested in the “master of the land.” He and his family usually acquired their position by force or by decision of the state, which used the expropriation and redistribution of ownership rights as means to enhance its power 4. The state acquired land which became vacant by virtue of emigration, absence of male inheritor, conviction for a criminal offence, or simple failure to cultivate.

Through his tax-collector the “master of the land” obtained several kinds of revenue from the “master of fire” and any tenant farmers working his fields. One was the assakal, derived from the Arabic zakaat (alms), and consisting of one-tenth of the harvest. The landowner also collected an annual fee of “entrance into cultivation” and a “repurchase” payment whenever the head of the farming family died. He shared these revenues with his tax-collector, with heads of families in his own lineage and with the provincial and central authorities. In addition, he paid a fee to these same authorities in return for “confirmation” in his position.

These rules made farming in the flood-plain problematic, in spite of its fertility. Rents and taxes were particularly heavy on tenants and “master of fire” families. Ownership and cultivation rights tended to fragment among male heirs with each passing generation, making it increasingly difficult to sustain an extensive and unified plot of land in one working unit. In addition, the amount of flooding varied from year to year, and it was thus impossible to predict the viability and yield of any given field. For all these reasons the Futankooɓe have a long tradition of migration to other parts of Senegambia, on both a seasonal and permanent basis 5.

The people of Futa also placed great store by fishing and animal husbandry. The fishermen formed a separate group and lived along the river and its tributaries, where they monopolized water transportation. Almost all fishermen and farmers kept some livestock. The donkeys served for transport, the cattle for milk, and the goats, sheep, and poultry for meat. Horses were expensive and belonged essentially to the wealthy who formed the cavalry in time of war. The pastoral specialists were the Fulɓe who tended their cattle in the southern jeeri and adjacent Ferlo, and exchanged services with the cultivators. They put the farmers' animals with their own herds in return for the right to let their cattle graze in the harvested fields, particularly during the dry season when there were no pastures in the Ferlo 6.

Over the centuries Futa Tooro has drawn many people to its soil and served as a kind of melting-pot. It has given shelter to fragments of ethnic groups from neighbouring areas: Soninke in the east, Wolofin the west. Moors to the north, and Fulɓe to the south. In addition, it has taken some of each of these ethnic ingredients, with Serer and Mandinka added for good measure, and fashioned a new people, the Tokolor 7. The Tokolor form the majority of the Futankooɓe and the dominant people of this story. They call themselves “speakers of Polar”, the language of the Fulɓe, and in the West African linguistic context might be considered a subdivision of the Fulɓe people. In the Senegambian usage followed here, however, Tokolor denotes the sedentary “Pular-speakers” rooted in the middle valley, while Fulɓe indicates the pastoralists who range through the southern jeeri and the Ferlo 8.

Futa Tooro has always supported a more dense population than most other parts of Senegambia and Mauritania. In the early twentieth century, the middle valley had approximately 260,000 inhabitants (see Appendix III), of whom about 60 per cent were Tokolor, 30 per cent Fulɓe and the remainder divided in roughly equal portions among the Wolof, Soninke, and Moors. The figure for the mid-nineteenth century was slightly larger, since the exodus occasioned by al-hajj Umar in the 1850s and the cholera epidemic of 1868-9 cancelled out the natural increase. For the last half of the nineteenth century, the over-all density can be estimated at eighty persons per square mile, with higher figures in the central region, lower ones in the western, and sharp drops towards the Ferlo in the south and the Mauritanian steppe and Sahara to the north. The average density compares with sixteen persons per square mile for Sin-Salum at the turn of the century and forty for all of Senegal today 9.

In common with the other people of Senegambia and Mauritania, the Futankooɓe can be divided into three basic strata: slaves, endogamous artisan castes, and persons of free status 10. The slaves included foreigners who had been recently purchased or captured, often subject to resale and harsh treatment, as well as families integrated for several generations into free or artisan households 11. The more integrated slaves sometimes had compounds, fields, and even slaves of their own, and were in the process of changing their stranger status into a Futanke (of Futa) identity. Most slaves originally came from the non-Muslim and non-Pular-speaking communities to the south-west (Wolof and Serer), south (Mandinka along the Gambia) and south-east (Mande-speaking people of the Upper Senegal valley). Although they lived in or near the compounds of their masters and shared similar work and diet, they did provide much of the labour force for the waalo and jeeri crops. The loss of slaves to French-controlled territory by flight, kidnapping, or purchase posed a significant threat to cultivation and the slave-owning class. The artisan castes included blacksmiths, jewellers, leather-workers, wood-workers, weavers, potters, and several sorts of entertainers and oral historians 12. In most cases they married within their own vocational group. They met the local demand for their skills, and often farmed on the side. They usually formed part of the entourage of a free family in the same village, and might be mobilized for military service or other duties by their overlord. While the free classes of the Fulɓe, Wolof, and Soninke consisted primarily of farmers, herders, and a few leading lineages, the picture in Tokolor society was more complicated. Dominating the Tokolor hierarchy were the tooroɓɓe (sing. tooroodo), the descendants of the group which seized power and created the Islamic regime of Futa in the late eighteenth century 13. Before that time, tooroɓɓe membership simply meant the practice of Islam and some rudimentary knowledge of the faith, and embraced persons of diverse social status and ethnic origin. After they came to power, however, the tooroɓɓe became a ruling class with inherited status. It is important to distinguish clearly, as the literature often does not, between

There were three classes of commoners in nineteenth-century Tokolor society.

Although the tooroɓɓe provided the national and much of the local leadership in Futa, the classes were not evenly distributed through the country and commoner lineages often dominated in particular villages and areas. The Tokolor sent their children to village schools to learn how to pray and recite selected passages of the Koran. Some of the male tooroɓɓe pushed their studies further and became the practising clerics of Futa, but the general level of knowledge of Arabic and Islam was not so high as among the scholarly class of Northern Nigeria 15. The founders of the tooroɓɓe regime had to complete their training outside of Futa and left very little literature to posterity because of their limited competence in Arabic. This deficiency did not, however, affect tooroɓɓe and Tokolor pre-eminence in Islam in Senegambia and particularly their perception of pre-eminence. According to two residents of the French colonial capital at St. Louis,

… [they] believe themselves to be, in their proud insolence, the first people in the world, the chosen children of God, for they alone, among the Muslim peoples, they say, properly observe the law of Muhammad.

They consider the blacks of Senegal to be infidels polluted by contact with Christians and call them, as well as us [the European and mulatto Christians of St. Louis], by the name of kaffirs (infidels, Jews [sic]) or gagnon Allah (enemies of God), and think it a meritorious act to pillage us 16.

The “blacks” from a Tokolor perspective were precisely those inhabitants of Senegal who did not speak Pular and were fair game for raiding and enslavement.

Children were not entirely raised in specifically Islamic institutions 17. Age-sets (pelle, sing. fedde) grouped boys and girls born at intervals of about three years and played important roles in social formation during adolescence. The fedde was particularly important for the young Tokolor men up through circumcision and until the time of marriage in their twenties. It was a means of organizing raiding expeditions to prove their valour, acquire slaves and other property, and generally set the stage for their own homes and families. After marriage the age-set had relatively little importance for either sex.

Marriage involved many political considerations for the Tokolor, be they influential tooroɓɓe wishing to consolidate their position, or slaves seeking to leave their past behind. It was the most readily available institution for creating alliances between families. If the union produced children, the bond could even survive a subsequent divorce ˇ a common event in Futa. Polygyny was permissible up to the Muslim limit of four, but even the wealthy seldom availed themselves of the maximum, and preferred their “multiple spouses” in serial form, achieved via divorce and remarriage. Although the Tokolor castes were endogamous, men could marry below their rank or outside of the society without incurring any significant risk for their descendants. Some stigma did attach, however, to the children of their concubines, who were often slaves captured or purchased in other areas 18. Women had a very limited public role. After acquiring the ability to recite the daily prayers, young girls confined their attention to the domestic compound and learning the arts of the home. They were married by parental decision at a much younger average age than the men. A wife of influential lineage added immensely to the reputation other husband, and her dowry, together with his bride wealth, laid the foundation of the new family. In cases of marital trouble, the wife's family stood behind her and might arrange a divorce in cases where she could not directly initiate action. Once divorced, a woman had much greater freedom in the choice of another spouse. In polygynous families children usually identified much more closely with the mother 19.

The principal focus of activity for the Tokolor was the village 20. The villages were far from uniform and ranged in size from fewer than a hundred to several thousand inhabitants. A mosque and local market usually shared the central square, while the residential quarters spread out in several directions and tended to group people of the same class or caste, the same entourage, or same date of arrival. Beyond these quarters, sometimes stretching to quite a distance, lay the fields farmed by the inhabitants. Representatives of the principal free lineages chose the village headman from one designated lineage and he, together with the imaam of the mosque, arbitrated most of the local disputes. Futanke justice was reputed to be quite severe in questions of property damage, adultery, theft, and murder, but the wealthy were usually able to attenuate sentences for themselves and their families. The relation between the village and the national level followed no particular pattern. Some villages were virtually autonomous, like the inaugural capital of Futa at Hore-Fonde. More frequently, the village formed part of a cluster under a paramount chief from a particular lineage. He might be of tooroɓɓe or commoner status and usually had the authority to tax the crops and herds, settle disputes that could not be resolved at the local level, and mobilize the able-bodied men for military campaigns. The province usually included several paramount chiefs and had little or no political or judicial structure. Some leaders, like the Lam Tooro of Tooro and the Wan of Law, did succeed partially in getting recognition of their authority at the provincial level. Above the province was the region, a term used here primarily for convenience, and finally the nation. At this last level was the Almamy or ruler of the tooroɓɓe regime, invested theoretically with the right to confirm and depose all lower office-holders, settle cases on appeal, and decide issues of war and peace. In reality, however, the Almamies of the nineteenth century had much less authority and rarely overruled the chiefs at any level. Most offices were ascribed in the sense of “belonging” to particular lineages and the eldest son usually had some advantages over his brothers, uncles, and cousins. Competition for these positions was none the less fierce, with the prize going to the candidate who best mobilized his potential constituency. Those losing the struggle sometimes took their followers to other areas of Futa or Senegambia. In addition, it was virtually impossible for a person to transfer to his son or any relative the particular combination of alliances, wealth, and power that he had fashioned for himself. Important chiefs were constantly vying with one another for supporters and their entourages tended to change rather frequently. This provided a kind of lateral mobility that contrasted with the relative absence of vertical mobility or change of social class 21.

Under a leader named Koli Teŋella, the Denyanke dynasty conquered Futa Tooro in the early sixteenth century and established the regime which controlled the middle valley for the next 250 years 22. Unlike most Fulɓe, they did become sedentary and practised Islam in the “court tradition” of the Western Sudan, whereby the king and his counsellors fulfilled the obligations of Islam and maintained clerics at court without abandoning traditional religious observances. The Denyanke kings or Saatigi were the most powerful rulers in Senegambia until the late seventeenth century, when pressures from the north began to impinge.

The first of these forces resulted from a struggle for power in Southern Mauritania between indigenous Berber and invading Arab elements 23. Nasir al-Din led the Berbers, who saw their movement as a jihaad (holy war) against the “enemies of Islam” and sought to establish the Shari'a or law of Islam as the basis of a new society and state. The Arab forces were inferior in Islamic learning but superior in military capacity, and defeated the indigenous armies conclusively in the 1670s. Their victory led to the social charter and vocational distribution which has characterized Mauritania and the Moors ever since. The Arabs or hassani appropriated the political and military functions and supplied the dynasties controlling the Trarza and Brakna confederations just north of the Senegal River. The losers became the zwaaya (clerical tribes) concerned with maintaining the Islamic heritage and with commercial questions. Although both groups sustained their pastoral mode of livelihood and had clients and slaves to do their manual labour, they did follow the basic vocational specialization and the zwaaya became the leading spokesmen for the faith in Senegambia as well as Mauritania.

Just before their downfall, the Berber or zwaaya forces extended their struggle to the south, allying with local Muslims to topple momentarily the Denyanke Satigi and the rulers of the Wolof states of Walo and Cayor. In each case the kings returned to power and restored the same syncretism of Islam and traditional practice that had existed before, but they were not able to eliminate entirely the precedent and memory of a society governed by the Sharii'a. In Futa the zwaaya effort corresponded with the emergence of some of the tooroɓɓe families who would play leading roles in the reform movement a century later 24.

In the early eighteenth century pressure of a different kind impinged upon the middle valley from the north, this time in the form of raiding by Mauritanian and Moroccan armies 25. Sultan Mulay Ismail of Morocco was looking for slaves to serve as soldiers and, with the collaboration of some of the hassani warriors, began to concentrate on the Middle and Upper Senegal in the 1720s and 1730s. The Moroccan and Mauritanian forces began making and “unmaking” Saatigi at will while the residents of the north bank of Central Futa took refuge on the southern shore. By the mid eighteenth century the Denyanke had abdicated responsibility for protecting their subjects in the central region and pulled back into the eastern end of Futa. Declining rainfall and poor harvest complicated the situation further, and raiding and migration continued into the 1760s and 1770s. One manifestation of the turmoil was a sharp increase in the number of slaves sold to the Europeans in Futa, which traditionally had been reluctant to participate in the Transatlantic slave trade 26.

Taking advantage of the swelling discontent, several tooroɓɓe of the central provinces created a reform movement in the 1760s and began to provide for their own defence 27. Their leader was Sulayman Bal, a cleric who had spent several years in the Islamic state of Futa Jalon, and enjoyed a reputation for skills in the “secret sciences” of Islam. By the early seventies, he had mobilized an army, weakened the Denyanke regime and pushed back the invading Moors.

The conflict between Denyanke and tooroɓɓe was articulated in terms of the contrast between the “court tradition” of Islam and the Fulɓe life-style, on the one hand, and the vision of a society governed by Islamic law, on the other. While the tooroɓɓe saw their opponents as “uncivilized” and “pagan”, the Fulɓe castigated the reformers as greedy, ambitious, and of humble origin. The Fulɓe perception was succinctly articulated in a number of proverbs preserved by Henri Gaden 28. Playing on the derivation of tooroɓɓe from a verb meaning “to ask for alms,” the Fulɓe would say : “The tooroodo is a beggar,” or “Don't hope to get a bubu [robe] from a tooroodo, even if he has many clothes he will still go out begging for a bubu.” Referring to the diverse and sometimes modest antecedents of the reformers, they remarked: “A tooroodo is a slave”, or “Even a fisherman who learns [Islam] can become a tooroodo.” They cast aspersions on tooroɓɓe claims to a new and special kind of authority, since “those who write are [just like] the magicians.” Nor did they have any illusions about the permanence of reform, since “the cleric gives birth to the chief, and the chief to the pagan.” By contrast, the Fulɓe praised their own generosity, mobility, and freedom from the obligations of Islam.

When Sulayman Bal was killed in battle in the 1770s, the tooroɓɓe had to face the problem of succession and translating the area of Central Futa which they controlled into a society governed by Muslim law. After some hesitation, they chose as their first official head of state a man named Abdul Kader Kan, a highly respected; fifty-year-old teacher with sterling credentials. He was the grandson of a pilgrim to Mecca, and had studied with the zwaaya clerics of the tradition of Nasir al-Din. He also spent several years at the Cayorian school of Pir, which other tooroɓɓe attended, and then taught for many years in the Upper Senegal. As chief of state, Abdul received the title Almamy, taken from the Arabic al-imaam (the person who leads in prayer). Futa Tooro thus followed the usage then current in the Islamic states of Bundu and Futa Jalon which hearkened back to the “imamate” envisaged by the Berbers in the seventeenth century 29. The new regime or “Almamate” lasted from the appointment of Abdul in the 1770s until the French conquest of 1891.

Almamy Abdul and his associates now confronted the task of putting flesh on the bones of the new state. The first problem was conquest, since the Denyanke still dominated the east and the Trarza Moors the west. After several battles against the last Saatigi, Abdul reduced them to a small area at the far end of Eastern Futa where they survived in virtual autonomy through the nineteenth century 30. In the west the Almamy enjoyed more spectacular success, defeating and killing the Trarza leader in 1786 with the help of the rival Moorish confederation of the Braknas 31.

Map II. Modern Futa Tooro

Source: Boutillier et al. Moyenne Vallée

Consolidation followed conquest, in the form of land grants to supporters of the regime, who were drawn from the tooroɓɓe, seɓɓe and noble Fulɓe strata. Some settled at crucial fords along the river to protect against attacks from the north, while others colonized the jeeri of Eastern Futa to defend that flank from the Denyanke. Still others received tax fiefs in Western Futa or moved back to the northern bank of the central provinces. Taken together, these measures helped restore the prosperity of the middle valley.

The next step was to institute the Shari'a or law of Islam. Abdul seems to have done this in a rather thorough way at the local level, by appointing imaams to lead prayer at the village mosques, judge offences, and arbitrate disputes. He also required village headmen and some paramount chiefs to pay a fee in exchange for confirmation in office, giving him some control over the choice and conduct of the leaders. On the provincial and regional levels, however, there is little evidence of appointments or institutionalization of any kind. It seems fair to conclude that the first Almamy approached the problem of governing Futa from his long and limited experience as a local teacher and judge and tried to keep personal control over village affairs.

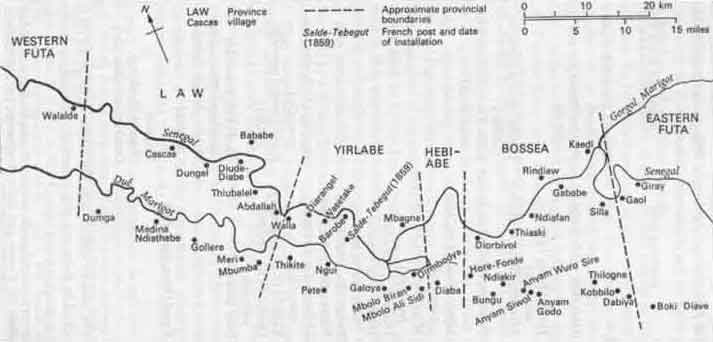

At the national level Abdul did have some assistance, particularly in the persons of two ministers recruited from leading Fulɓe lineages of Central Futa 32. Ali Sidi Ba of Yirlabe province took care of “western affairs,” meaning all matters arising in Western Futa and the western half of the central region. Ali Dundu Kan of Bossea, grandfather of Abdul Bokar, managed the eastern half of the kingdom. Almamy Abdul had his capital at Thilogne in Bossea. He was the final judge of appeals and the only person who could order the execution of a criminal. He was commander of the army in principle, if not always in practice, and decided when to organize a jihaad or a simple raid. He distributed the millet and cloth which constituted the state treasury, allocating portions to military campaigns, government officials, the maintenance of roads, and the relief of the poor. Treasury revenues came from the “tenth,” or assakal, confirmation fees, a portion of the booty from military campaigns, and other sources 33.

The principal external contribution to the treasury was the “customs” or annual payment made by the French for the rights of trade in Futa and access to the upper river. In a treaty passed with the Governor of St. Louis in 1785, Almamy Abdul fixed the fees and forbade the capture and exportation of slaves from the middle valley. He appointed an Alcaty or “minister of European affairs” from a leading tooroɓɓe lineage of Mbolo Biran in Central Futa 34. The Alcaty handled treaty negotiations with the French and presided over the ceremonies accompanying the passage of the annual French convoy to the Upper Senegal.

The new regime also sought to spread its version of Islam to other parts of Senegambia, building upon the reputation and contacts of the first Almamy. Futanke expeditions in the Upper Senegal went to the aid of Muslim traders and teachers and tried to force the rulers of Gadiaga, Khasso, and even the ostensibly Muslim dynasty of Bundu to adhere to the Shanfo 35. In the west, a century after the original effort by the Mauritanian reformers, the tooroɓɓe achieved some success in pressuring the Wolof rulers of Walo, Jolof, and Cayor to toe the Muslim line 36.

Then things fell apart. In 1796 a large Futanke army sallied forth to challenge the claims of a new and assertive Damel of Cayor. The Wolof king filled all of the wells along the army's route and exterminated the exhausted Futankooɓe at the battle of Bunguye, taking the proud and ageing Abdul prisoner. News of the Damel's victory spread rapidly and local accounts recorded at the time leave little doubt as to where much Senegambian sentiment lay. The following version was heard by Mungo Park over 300 miles from the scene a few months later:

The behavior of Damel on this occasion is never mentioned by the singing men but in terms of the highest approbation; and it was indeed so extraordinary in an African prince, that the reader may find it difficult to give credit to the recital. When his royal prisoner was brought before him in irons, and thrown upon the ground, the magnanimous Damel, instead of setting his foot upon his neck, and stabbing him with his spear, according to custom in such cases, addressed him as follows:

ˇ Abdulkader, answer me this question: if the chance of war had placed me in your situation, and you in mine, how would you have treated me?

ˇ I would have thrust my spear into your heart, returned Abdulkader with great firmness; and I know that a similar fate awaits me.

ˇ Not so, said Damel ; my spear is indeed red with the blood of your subjects, and I could now give it a deeper stain by dipping it in your own; but this would not build up my towns, nor bring to life the thousands who fell in the woods. I will not, therefore, kill you in cold blood, but I will retain you as my slave, until I perceive that your presence in your own kingdom will be no longer dangerous to your neighbours, and then I will consider of the proper way of disposing of you.

Abdulkader was accordingly retained, and worked as a slave for three months; at the end of which period, Damel listened to the solicitations of the inhabitants of Foota Torra, and restored to them their king 37.

Disaster abroad was followed by dissension at home 38. The Futankooɓe did not take kindly to the defeat at Bunguye and the humiliating captivity of the chief of state. Furthermore, Abdul's personal style of rule and stern application of Islamic justice made many enemies, especially when applied to the most influential families. Ali Sidi was the first of the inner circle to bridle, in his case at the punishment meted out to his relatives. After several skirmishes he went into exile among the Denyanke and harassed the Almamy from there. Then the leading family of Thilogne drove Abdul from the capital and Ali Dundu grew disenchanted. The Almamy's isolation was virtually complete.

The end came abruptly in 1806-7. Armies from Bundu and the Bambara kingdom of Karta, incensed at Futanke intervention in their affairs, invaded the middle valley, coordinated efforts with the disenchanted tooroɓɓe and chased Abdul from his kingdom. A few months later, according to the account heard by a British explorer a decade after the events, Almamy Amadi [of Bundu], accompanied by the Kartan army, and part of his own, soon met him [Abdul Kader], when a bloody, though unequal conflict ensued, ending in the death or capture of every one of Abdoolghader's men. He himself descended from his horse, and sat down on the ground to count his beads and say his prayers, in which situation he was found by Almamy Amadi, who, having saluted him three times in the usual manner without receiving an answer, said:

ź Well! Abdoolghader, here you are; you little thought, when you murdered my brother, Amadi Sega, that this sun would ever dawn on you; but, here, take this, and tell Sega, when you see him, that it was Amadi Isata sent you ╗; and, drawing out a pistol, put an end to his existence.

He is said to have received the ball with all the indifference imaginable. He was upwards of eighty years of age 39.

In death the man who had alienated his most powerful supporters became a martyr who inspired the hopes of Futankooɓe for a more just and truly Islamic society.

There were three principal reasons why the centralized Islamic state envisaged by some of the early tooroɓɓe did not come to pass.

Prominent among these new lieutenants were persons of noble Fulɓe extraction, like Ali Sidi Ba of Yirlabe and Ali Dundu Kan of Bossea, men who would join in campaigns and collect taxes but not willingly subject their own lineages and followers to the chapter and verse of Abdul's teaching. In fact, they retained much of their Fulɓe life-style, contacts with Fulɓe kinsmen, and critical attitudes towards reformers. Their disillusionment undermined the regime and opened the way for invasion from the east 40.

One of these chiefs of recent Fulɓe extraction, Ali Dundu, emerged as the single most powerful leader of Futa between 1807 and his death in 1819. Under his influence, the regime assumed the character which it conserved through most of the nineteenth century. While Futa retained the charter of the Almamate ruled by a learned Muslim according to the Shari'a, the key institution became a council of jaggorDe (electors ˇ sing., jaggorgal) drawn from the provinces of Bossea and Yirlabe 41. In Fulɓe tradition, the jaggorgal was one who gave support and counsel to a chief, as Ali Dundu and Ali Sidi had initially done for Abdul Kader. In the new situation he was to be a king-maker and decide the major issues of war and peace. In 1818 the explorer Mollien made the following observations about the council and Futa:

Futa Tooro is now a sort of theocratic oligarchy, in which the people possess considerable influence. Ali Dundu, Eliman Sire [son of Ali Sidi], … [and five other leaders] are the chiefs of the country. They are probably descendants from the ancient chiefs of the Pula [Tokolor and Fulɓe] tribes when they were a wandering people. Each of them is proprietor of a portion of the country, and they jointly exercise the sovereign authority. The first two always enjoy a kind of pre-eminence over the others, for their two voices form a majority in the council ; but to give their decrees greater weight with the people, they create an Almamy (Imam), whom they select from among the common Marabuts [clerics]. All the acts of government are performed in his name, but this Almamy cannot take any step without consulting his council. When they are dissatisfied with this chief, they retire during the night to an elevated spot, and after a long deliberation the Almamy is deposed and another immediately elected in his stead. They desire his attendance, and address him in these words: “We have chosen thee to govern our country with wisdom”; and no doubt they add, “and to execute our commands”. The Almamy then takes the Koran and says, “I will strictly follow that which the book of God prescribes ; if he commands me to give up my wealth, to sacrifice my children, I will do it without hesitation.” Upon this, Ali Dundu on one side and Eliman Sire on the other, present the new Almamy to the people, saying: “Here is your king, obey him.” The people applaud, and the elevation of the new prince to the throne is celebrated by salutes of musketry. The Almamy makes presents to the seven chiefs, and in his turn receives donations of flocks and slaves from the people… 42.

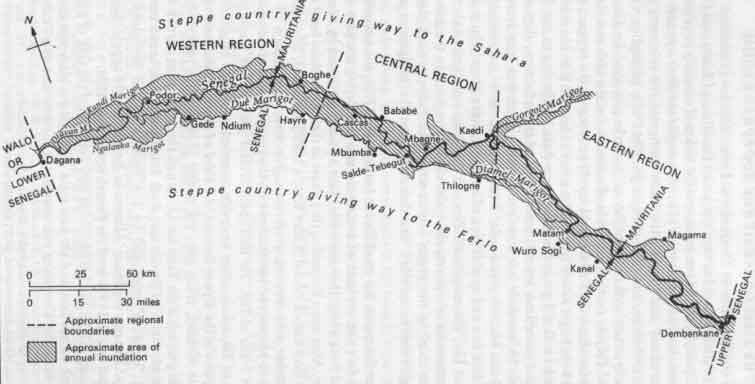

The electoral council fluctuated in size, composition, and alignments during the nineteenth century, but five lineages from Bossea and Yirlabe dominated its deliberations. The Bossea families were the Kan of Dabiya (Ali Dundu's line), the Ly from the Thierno Molle lineage of Thilogne, and the Atch from the Eliman Rindiaw lineage of Rindiaw. The Yirlabe families were the Ba of Mbolo Ali Sidi and the An from Pete. The council did not meet at any regular interval but rather on the call of one of its more influential members, usually to consider the election or deposition of a chief of state. To select an Almamy, all the jaggorDe apparently had to agree; to depose, a majority or even an influential minority sufficed 43. Since the Almamy was the symbol of the prosperity, territorial integrity, and unity of Futa, the electors usually changed leaders after a bad harvest, serious raid, or civil strife. The result was rapid turnover, frequent interregnums and tremendous competition over candidates.

In an effort to prevent the emergence of another strong ruler like Almamy Abdul, the electors did not create an administrative capital in Futa. Instead, they made Hore-Fonde, a wealthy and largely autonomous village on the edge of Bossea, into a ceremonial centre where they announced their choice as chief of state to the assembled paramount and village chiefs. The candidates came from a different set of tooroɓɓe lineages, those of older vintage and greater Islamic instruction and collectively called laamotooɓe or “eligibles”.

Most of the eligible families hailed from Hebiabe and Law provinces in the central region or from villages in Eastern and Western Futa established by the tooroɓɓe in the eighteenth century. After the installation in Hore-Fonde, the new Almamy took a tour of Futa to announce his accession and receive the gifts and acclaim of the populace. Then he returned to his native village and reigned from there until deposed. As chief of state, he ostensibly controlled revenues from crops, herds, confirmation fees, and the annual customs duty paid by the French.

He could confiscate estates belonging to criminals or lacking male inheritors, and redistribute them to the electors or other allies. Once removed from office, the possessions which he had accumulated during his tenure were fair game for the new Almamy and his chiefs 44.

The tooroɓɓe also refused to create a standing military force of any kind. In the words of two observers from St. Louis,

Futa has no permanent militia: when the country is at war, each chief gathers the men of his village or province. But such armies, whose units are independent [of any central control], are not known for their courage or discipline. It suffices to win over a chief, whose withdrawal always succeeds in disorganizing the army. Or, if he refuses to be that decisive, he simply requests an assembly. There, in the interminable speeches … questions become so confused that disunity is sown among the leaders and the army disperses. In any case, their spirit of insubordination, which they call love of liberty, is such that they can never maintain a campaign for very long 45.

The electors and the Almamy seldom agreed on a military campaign and registered no notable successes on the field of battle in the first half of the nineteenth century, in spite of the relatively large number of horses and guns which they possessed. In fact, on several occasions the Bambara of Karta invaded the middle valley, confiscated crops and cattle, and enslaved local citizens 46.

An analysis of the reigns of Almamies testifies to the competition and instability of the tooroɓɓe regime. According to the best available data, twenty “eligibles” served forty-five different terms as Almamy between 1806 and 1854 47. Adding in at least twelve interregnum periods totalling about five years, one has an average length of reign of less than one year. Three qualifications must be mentioned, however.

One additional feature of the tooroɓɓe regime in the nineteenth century was the privileged position of the central region and the unfavourable situation of Western Futa. The western region had no representation on the electoral council and, except for the Hayre village cluster, furnished no candidates for the Almamyship. Most of its communities were divided up into tax fiefs for the electoral families. In Eastern Futa, there were relatively few such tax estates and some villages did provide candidates to the council 49.

One eligible family, the Wan of Mbumba (Law), made a concerted effort to neutralize the authority of the electors and establish themselves as a ruling dynasty in the middle valley. Biran and his son Mamadu consolidated their territorial base in eastern Law and acquired a large number of slaves through raiding to the south. They reconquered some of the northern bank from the Moors and redistributed the land to family and friends. When deposed from the Almamyship, they continued to collect revenues from the office-holders of Law that ordinarily would have gone to the new chief of state and, using their predominantly slave army, usually succeeded in preventing the rival Ly coalition from raiding their possessions 50.

Table I

Schematic Presentation of Principal Villages and Families in the Nineteenth Century

| southern jeeri | waalo and north bank | |

| Province or area | ||

| Dimar | Dagana (French fort and village) | |

| Tooro | Gede (Sal, noble Fulɓe) | Podor (French fort and village) |

| Hayre | Hayre (Baro, Ture, tooroɓɓe) | |

| Law | Mbumba (Wan, tooroɓɓe) | Cascas (several tooroɓɓe, seɓɓe) |

| Yirlabe | Pete (An, electoral tooroɓɓe) | Salde-Tebegut (French fort and village) |

| Mbolo Biran (Kan, Alcaty, tooroɓɓe) | ||

| Mbolo Ali Sidi (Ba, electoral tooroɓɓe) | ||

| Hebiabe | Diaba (Ly, tooroɓɓe) | |

| Bossea | Hore-Fonde (several tooroɓɓe, seɓɓe) | |

| Bungu (Ba, noble Fulɓe) | ||

| Ndiakir (Ba, noble Fulɓe) | ||

| Thilogne (Ly, electoral tooroɓɓe) | Rindiaw (Atch, electoral tooroɓɓe) | |

| Kobbilo (Kan, tooroɓɓe) | Kaedi (several tooroɓɓe seɓɓe) | |

| Dabiya (Kan, electoral tooroɓɓe) | ||

| Ngenar | Boki Diave | Gaol (Any, tooroɓɓe) |

| Ngidjilogne (Dia, seɓɓe) | ||

| Matam (French fort and village) | ||

| Damga | Kanel (Wan, tooroɓɓe) | |

| Magama | ||

| Waunde (Soninke) | ||

| Dembankane (Soninke) | ||

Beyond the provincial level, Biran and Mamadu succeeded equally well. They constructed an important network of support through marriage alliances, of which three were particularly important. Through links with the An of Pete and the Ly of Thilogne, they countered the opposition of Eliman Rindiaw Falil, the most influential elector in the decades after Ali Dundu. By allying with the Kan of Mbolo Biran, the Wan leaders were able to obtain a large proportion of the customs duties paid by the French even when they were not serving as Almamies of Futa. By the 1850s Mamadu, or Mamadu Biran as he was usually called, was the single most powerful and wealthy individual in Futa and was constantly receiving suitors for the hands of his daughters and nieces 51.

Map III. Central Futa Tooro

Adapted from Feuille 2b of M.F. Bonnet-Dupeyron, Cartes de l'Elevage pour le Sénégal et la Mauritanie (Paris, MFOM, 1951)

The Wan exemplified the larger process of change from the original tooroɓɓe movement of Sulayman Bal and Abdul Kader. The early reformers had given way to electoral and eligible lineages who combined in coalitions to compete for the Almamyship and the spoils of office. In the mid-nineteenth century the tooroɓɓe included three main categories.

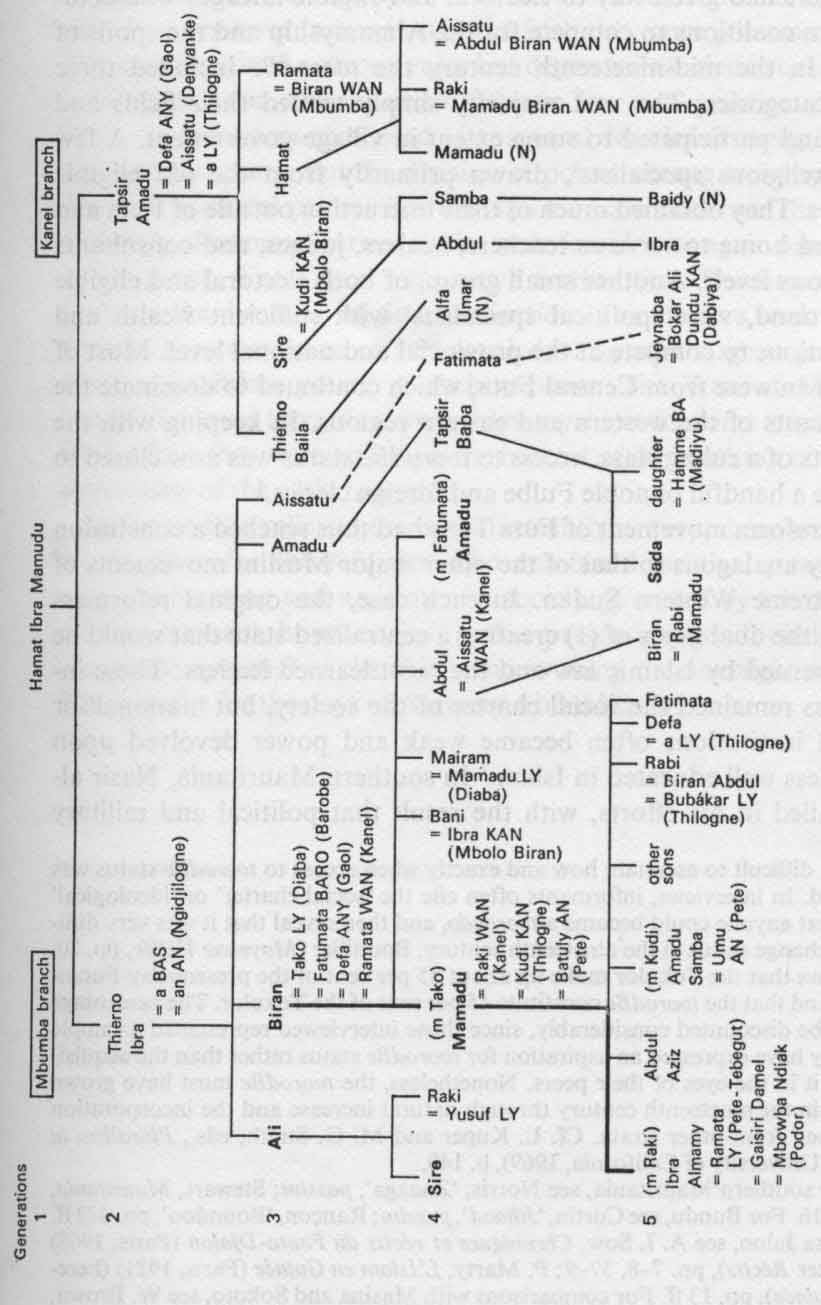

Table II. Genealogy of the Wan Famility (partial list)

Most of these men were from Central Futa, which continued to dominate the inhabitants of the western and eastern regions. In keeping with the interests of a ruling class, access to tooroɓɓe status was now closed to all save a handful of noble Fulɓe and foreign clerics 52.

The reform movement of Futa Tooro had thus reached a conclusion broadly analogous to that of the other major Muslim movements of the extreme Western Sudan. In each case, the original reformers sought the dual goals of (1) creating a centralized state that would be (2) governed by Islamic law and the most learned leaders. These intentions remained the social charter of the society, but “national” or central institutions often became weak and power devolved upon those less well educated in Islam 53. In southern Mauritania, Nasir al-Din failed in his efforts, with the result that political and military responsibilities fell to the hassani Moors, while the zwaaya took charge of commerce, learning, and arbitration. In Bundu, the Sy family achieved political control in the late seventeenth century, but soon lost whatever instruction in the faith they once possessed. Their Almamy remained a strong ruler but depended on clerics outside the royal family for counsel about Islamic law and practice. In Futa Jalon the reformers succeeded after several decades of struggle in the eighteenth century, but the division of power among two royal families (Alfaya and Soriya) and powerful princes like the Alfa mo Labe weakened the central authority. The most learned clerics were found once again outside the ruling group. Futa Tooro went much further than Bundu and Futa Jalon in the direction of decentralization. The electors took care to prevent the emergence of any royal dynasty and large capital that could consolidate power at their expense. The Wan of Mbumba fought the trend towards a weak Almamyship with some success, but by this time they were no longer the bearers of the tradition of Islamic instruction of the early tooroɓɓe.

In the middle valley in the mid-nineteenth century, there seemed to be no place for the reformer who combined political power with religious learning and a vision of a society governed by Islamic law. At that moment, however, just such a person appeared, challenging the modus operandi of the chiefs and evoking the nostalgia of many Futankooɓe for the days of Almamy Abdul Kader.

Notes

1. H. Gaden, Proverbes et maximes peuls et toucouleurs (hereafter Proverbes) (Paris, 1931), p. 310. Mr. Gaden served as Governor of Mauritania and was well-versed in the language and customs of the Pular-speaking people. Many of his papers are contained in the Fonds Gaden, IFAN.

2. Some of the Fulɓe (sing. Pullo) were complete nomads and ranged far to the south during the rainy season. Others were semi-nomadic and remained close to the river valley. The Fulɓe are also called the Fulani (the Hausa word for Fulɓe).

3. The best summary of the patterns of land tenure of Futa Toto is J. L. Boutillier, P. Cantrelle, J. Causse, C. Laurent, and Th. N'Doye, La Moyenne Vallée du Sénégal (hereafter Boutillier, Moyenne Vallée) (Paris, 1962), pp. 111 ff.

4. For specific redistributions, the best sources are two rather obscure reports done in the early twentieth century : Lieutenant Cheruy, “Rapport sur les droits de propriété des Colade dans le Chemama et le mode d'élection des chefs de terrains”, appearing in the Supplément au Journal Officiel de l'Afrique Occidentale Française, nos. 52-4 (1911) (hereafter “Rapport”); and Administrateur Vidal, “Rapport sur l'étude de la tenure des terres indigènes au Fouta dans la Vallée du Sénégal”, mimeographed in 1924 as Bulletin 72 of the Archives of the Mission de l'Aménagement du Sénégal (hereafter “Tenure”). The principal redistributions occurred under:

5. Several sources indicate that migration from the middle valley was already frequent in the early and mid nineteenth century. See Abbé P. D. Boilat, Esquisses sénégalaises (Paris, 3853) (hereafter Esquisses), pp. 388 ff.; Gaspard Mollien, Travels in the Inferior of Africa (London, 1820, trans. from the French) (hereafter Travels), pp. 115-33.

6. For the symbiotic relations between pastoralists and agriculturalists, see G. P. Murdock, Africa. Its Peoples and Their Culture History (New York, 1959), p. 416.

7. Tokolor is derived from Takruur, the ancient Arabic term for the middle valley. The best summary of the meanings associated with Takruur is Umar al-Naqar, “Takruur, the history of a name”, JAH 10.3 (1969), pp. 365-74.

8. The question of Fulɓe origins and migrations is subject to great debate. For a recent discussion of the subject by a linguist, see R. G. Armstrong, The Study of West African Languages (Ibadan, Nigeria, 1965), pp. 4-7,25-8.

9. See Appendix III.

10. The best descriptions of Tokolor social structure are Yaya Wane, Les Toucouleurs du Fouta Tooro. Stratification sociale et structure familiale (Dakar, IFAN, 1969) (hereafter Toucouleurs) ; Gaden, Proverbes, pp. 313 ff. For a description of social and cultural values of the Tokolor, see Boubakar Ly, “L'Honneur et les valeurs morales dans les sociétés Ouolof et Toucouleur du Sénégal. ╔tude de sociologie”, (Thèse de troisième cycle, Sorbonne, 1966, two volumes) (hereafter “Honneur”), passim. For a comprehensive view of all the Futankooɓe, see Boutillier, Moyenne Vallée, pp. 19-59. Scholars writing on Senegambian societies often use the word “caste” to apply to all strata of the population, but I have chosen not to apply it to the slave or free groups where there is somewhat less endogamy and somewhat more vertical mobility. For a discussion of this issue, see Wane, Toucouleurs, pp. 29 ff.

11. This follows the usual division made between domestic slaves and “trade” slaves. Cf. J. S. Trimingham, Islam in West Africa (Oxford, 1959), pp. 132-5. For a recent discussion of slavery and serfdom in Futa Jalon, see William Derman, Serfs, Peasants and Socialists (University of California, 1973), pp. 27-42.

12. The three castes of oral historians are the awluBe (sing. gawlo), wambaaBe (sing. bambaaDo), and maabuBe (sing. maabo). The last group are also weavers. For a discussion of these groups as sources of history, see this author's article, “The Impact of Al-Hajj 'Umar on the Historical Traditions of the Fulɓe”, Journal of the Folklore Institute, Vol. VIII (1971), pp. 101-13. For a discussion of all the artisan castes, see Wane, Toucouleurs, pp. 50-67.

13. Gaden (Proverbes,pp. 153-4, 316-17) derives tooroɓɓe from the verb tooraade, meaning “to ask for alms”. Shaykh Musa Kamara, the noted teacher and historian of Futa Tooro in the early twentieth century, suggests a derivation from Tooro, the province of Western Futa which has a longer recorded history than any other part of the middle valley. His view can be found in his long Arabic history of Futa Tooro, Zuhuur ul-Basaatiin fii Ta'riikh is-Sawaadiin (Manuscript Room, IFAN) (hereafter Zuhuur), Vol. I, f. 149. For a French translation of this passage, see Amar Samb, translator and annotator, “La Vie d'El Hadji Omar par Cheikh Moussa Kamara”, (Bulletin de l'IFAN, B, 32 [1970], pp. 44-135, 370-411, 770-818) (hereafter Samb, “Omar par Kamara”), p. 801.

14. As an example of the confusion, see the nineteenth century account of two residents of St. Louis, Frédéric Carrère and Paul Holle, De la Sénégambie française (Paris, 1855) (hereafter Sénégambie), pp. 123-7.

15. The relatively low level of learning of even the founders of the Islamic state (see my tape collection, FR, Thierno Dahirou Anne, session 2) contrasts with the erudition and vast literature left by Uthman dan Fodio and those associated with him (cf. D. M. Last, The Sokoto Caliphate, New York, 1967 [hereafter Sokoto], introduction).

16. Carrère and Holle, Sénégambie, pp. 131-2.

17. For what follows, see M. Dupire, Organisation sociale des Peul (Paris, 1970) (hereafter Organisation), pp. 45 ff; Gaden, Proverbes, pp. 22-6; Wane, Toucouleurs passim.

18. As in the case with Abdul Aziz Wan, son of Mamadu Biran by a concubine, in the late nineteenth century. See FR, Ali Gaye Thiam, session 3 ; FR, Cheikh Bandel Wane.

19. Wane, Toucouleurs, pp. 102-4. It was customary to adopt the first name of one parent as one's second name. Abdul Bokar was, for example, Abdul, the son of Bokar. In the nineteenth century, he often went by “Abdul Jeynaba”, thereby designating his mother. Since Islamic custom has placed the emphasis on paternal descent and the father's name, I have adopted that usage here. Information from interview with Oumar Ba, Dakar, 23 February 1969.

20. For village studies in Futa Tooro, see Z. Le Blanc, “Un Village de la Vallée du Sénégal : Amadi-Ounaré”, Cahiers d'Outre-Mer, 17 (1964), pp. 117-48 ; F. Ravault, “Kanel. L'Exode rural dans un village de la Vallée du Sénégal”, Cahiers d'Outre-Mer, 17 (1964), pp. 58-80.

21. Charles Stewart makes the same observation for southern Mauritanian society in Islam and Social Order in Mauritania (Clarendon Press, 1973) (hereafter Mauritania), pp.61-5.

22. The best overview of the Denyanke period is J. Boulègue, “La Sénégambie du milieu du XVe siècle au début du XVIIe siècle” (Thèse de troisième cycle, Paris, 1968) (hereafter “Sénégambie”), pp. 213 ff.

23. For the seventeenth-century reform movement, see P. D. Curtin, “Jihaad in West Africa: early phases and interrelations in Mauritania and Senegal”, JAH 12.1 (1971), pp. 11-24 (hereafter “Jihaad”); P. Marty, L'Islam et les tribus Maures. Les Brakna (Paris, 1921) (hereafter Brakna), passim; H. T. Norris, “Znaaga Islam”, Bulletin of SO AS, 32 (1969), pp. 496-526 (hereafter “Znaaga”); Stewart, Mauritania, pp. 12-16.

24. For the zwaaya effort in the south, see Curtin, “Jihaad”, passim; C.I.A. Ritchie éd., “Deux textes sur le Sénégal (1673-77)”, Bulletin de l'IFAN, B, 30 (1968), pp. 289-353. For tooroɓɓe who emerged at this time, particularly Lamin Kan, grandfather of the first Almamy of Futa, and Malik Sy, founder of the state of Bundu, see FR. Mamadou Dia, session 3; Kamara, Zuhuur, I, ff. 149 ff., 263, 268, and n ff. 183,190.

25. P. D. Curtin, éd., Africa Remembered (University of Wisconsin, 1967), pp. 31 ff.; A. Delcourt, La France et Ses établissements français au Sénégal entre 1713 et 1763 (IFAN, Dakar, 1952) (hereafter ╔tablissements), pp. 139-75; Noms, “Znaaga” passim.

26. B. Barry, “Le Royaume du Walo, 1659-1859” (Thèse de troisième cycle, Paris, 1970) (hereafter “Royaume”), pp. 198 ff; Kamara, Zuhuur, I, f. 175; P. Marty, éd., “Chroniques de Oualata et de Nema”, Revue des ╔tudes Islamiques, 1 (1927), p. 565; personal communication from Philip D. Curtin.

27. For what follows I have drawn on the oral traditions contained in FJ, Alfa Seybane Aw ; FR, Thierno Dahirou Anne, sessions 1 and 2; FR, Thierno Amadou Bokar Alfa Ba, session 1 ; FR, Mamadou Dia, session 2; FR, Ma Diakhite Cisse Kane, sessions 1, 3 and 4; FR, Thierno Seydou Kane, sessions 1 and 4; FR, Sega Niang, sessions 1 and 2; PR, Thierno Yaya Sy, session 2; Kamara, Zuhuur, I, ff. 263 ff. For published accounts of portions of the events of the late eighteenth century, see S. M. A. Golbéry, Fragments d'un voyage en Afrique. en 1785-7 (Paris, 1802) (hereafter Fragments), I, pp. 242 ff.; Major W. Gray and Staff Surgeon Dochard, Travels in Western Africa (London, 1825) (hereafter Travels), pp. 182-235; Saugnier and Brisson, Voyages to the Coast of Africa (London, 1792) (hereafter Voyages), pp. 180 ff., 289 ff. ; Sire Abbas Soh, Chroniques du Fouta sénégalais (Paris, 1913; translated, edited, and annotated by Maurice Delafosse with the aid of Henri Gaden) (hereafter Chroniques), pp. 33 ff.

28. All the proverbs are from Gaden, Proverbes, pp. 68, 315-18.

29. Curtin, Africa Remembered, p. 27; Curtin, “Jihaad,” passim.

30. Gray and Dochard. Travels, pp. 194-207; Kamara, Zuhuur, I, ff. 178-80,216, 282 ff., 331. The villages primarily associated with the Denyanke group in the nineteenth century are Barkedji, Lobali, Padalal, Sange, and Wali Diantan.

31. Golbéry, Fragments, I, pp. 257 ff.

32. Kamara, Zuhuur, II, f. 26.

33. It is not clear whether the Almamy and the treasury got the traditional one-fifth of booty specified in Islamic law. Cf. J. Schacht, An Introduction to Islamic Law (Clarendon Press, 1964) (hereafter Introduction), p. 136.

34. Alcaty is derived from al-qaaDi, Arabic for “judge” (R. Mauny, Glossaire des expressions et termes locaux employés dans l' Ouest Africain [IFAN, Dakar, 1952] [hereafter Glossaire], p. 18) or, perhaps, from al-kaatib, Arabic for “scribe”. The Alcaty appointed by Almamy Abdul was Tapsir Sawa Kudi Kan, who had previously performed similar functions for Satigi Konko Bu Musa. Kamara, Zuhuur, I, ff. 175-6. For the treaties of 1785,1804, and 1806 between Futa and the French, see ANS 13G9, section V, pièces 24-6.

35. FR, Sega Niang, sessions 2 and 4; FR, Thierno Seydou Kane, sessions 1 and 4; Gray and Dochard, Travels, pp. 194-207; Kamara, Zuhuur, I, ff. 155-7; Mungo Park, The Travels of Mungo Park (London, 1907, 1960, edited by Ronald Miller for Everyman's Library) (hereafter Travels), pp. 59, 261-3.

36. Barry, “Royaume”, pp. 198 ff. ; Lucie Colvin, “Kajor and its Diplomatie Relations with Saint-Louis du Sénégal, 1763-1861” (Ph.D., Columbia University, 1972) (hereafter “Kajor”), pp. 166-7; Kamara, Zuhuur, I, ff. 219, 281.

37. Park, Travels, pp. 262-3.

38. For what follows, see FR, Bokar Elimane Kane; FR, Kalidou Gaidio; Kamara, Zuhuur, I, ff. 276, 282 ff.

39. Gray and Dochard, Travels, pp. 198-9. See also André Rançon, “Le Boundou”, Bulletin de la Société de Géographie Commerciale de Bordeaux, 2nd series, 17 (1894), pp. 507-9 (hereafter “Boundou”); Soh, Chroniques, pp. 59-60.

40. For a list of those who plotted against Almamy Abdul, see Soh, Chroniques, pp.54-6.

41. For the electoral council and the division into “electoral” and “eligible”, see FJ, Alfa Seybane Aw; Carrère and Holle, Sénégambie, pp. 123-37; Mollien, Travels, pp. 142-4. Jambur or jambureeBe is used in Futa to designate electors at a village or provincial level and in Jolof to denote the electors of Fulɓe leaders. Communication from Oumar Ba, 22 November 1970; Dupire, Organisation, pp. 258 ff.

42. Mollien, Travels, pp. 160-1.

43. For the operation of the institutions of Futa in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, see FR, Thierno Seydou Kane, session 1 ; Carrère and Holle, Sénégambie, pp. 123-7; Kamara, Zuhuur, I, ff. 275-6, 346, and II, ff. 40-1, 160, 183 ff.

44. FR, Ma Diakhite Cisse Kane, session 2; FR, Thierno Seydou Kane, session 1 ; Kamara, Zuhuur, II, S. 41-2, 65a, 131.

45. Carrère and Holle, Sénégambie, p. 131.

46. Former Governor Bouet-Willaumez estimated that Futa Tooro had 30,000 guns in 1852, more than any other part of western and riverine Senegal except Cayor. Revue des Deux Mondes, June 1852, p. 942. For descriptions of mobilization, see FR, Kalidou Gaidio (for Bunguye) ; Mollien, Travels, pp. 145 ff. (for an 1818 expedition). For the Bambara invasions of Futa in the nineteenth century, see Kamara, Zuhuur, I, ff. 179-82, 283-8, 297-9, 345-7; Samb, “Omar par Kamara”, pp.804-18.

47. See D. Robinson, P. Curtin, and J. Johnson, “A Tentative Chronology of Futa Tooro from the Sixteenth through the Nineteenth Centuries”, Cahiers d'╔tudes Africaines, 12 (1972) (hereafter 'Chronology'), pp. 574-6.

48. Yusuf Ly of Diaba reigned for eleven terms over the span 1818-35 ; Babaly Ly of Diaba succeeded him as the “Ly” candidate and reigned for four terms over the period 1836-47. For the Wan, Biran reigned five times between 1817 and 1836 while his son Mamadu reigned eight times between 1841 and 1854, and three times between 1856 and 1864. 49. For the tax fiefs, see ANS 1G294 (“Monographie du Cercle de Podor”, 1904); Kamara, Zuhuur, II, ff. 4,9,15, 59, 65a.

50. FR, Thierno Seydou Kane, sessions 1 and 4; FR, Birane Amadou Samba Wane; FR, Mamadou Amadou Mokhtar Wane; Cheruy, “Rapport”, pp. 3-22; Kamara, Zuhuur, II, ff. 183-99; Soh, Chroniques, pp. 61 ff.; Vidal, “Tenure”, pp. 33-45. 51. The Wan did not develop close ties with Ali Dundu, the family of Ali Sidi or the Eliman Rindiaw. Cf. Carrère and Holle, Sénégambie, pp 200-2; Kamara, Zuhuur, II, 11,41-2,187; Soh, Chroniques, pp. 157 ff.

52. It is difficult to ascertain how and exactly when access to tooroɓɓe status was curtailed. In interviews, informants often cite the “social charter” or “ideological” view, that anyone could become a tooroodo, and then reveal that it was very difficult to change status in the nineteenth century. Boutillier (Moyenne Vallée, pp. 20, 54) shows that the Tokolor make up about 55 per cent of the present-day Futankooɓe and that the tooroɓɓe constitute 45 per cent of the Tokolor. The percentage should be discounted considerably, since those interviewed represented a sample and may have expressed an aspiration for tooroɓɓe status rather than the acquisition of it in the eyes of their peers. Nonetheless, the tooroɓɓe must have grown rapidly in the nineteenth century through natural increase and the incorporation of women from other strata. Cf. L. Kuper and M. G. Smith, eds. Pluralism in Africa (University of California, 1969), p. 140.

53. For southern Mauritania, see Morris, “Znaaga”, passim; Stewart, Mauritania, pp. 12-16. For Bundu, see Curtin, “Jihaad”, passim; Rançon, “Boundou”, pp. 472 ff. For Futa Jalon, see A. I. Sow, Chroniques et récits du Fouta-Djalon (Paris, 1968) (hereafter Récits}, pp. 7-8, 37-9; P. Marty, L'Islam en Guinée (Paris, 1921) (hereafter Guinée), pp. 13 ff. For comparisons with Masina and Sokoto, see W. Brown, “The Caliphate of Hamdullahi ca. 1818-64” (Ph.D., University of Wisconsin, 1969) (hereafter 'Caliphate'), pp. 121-49; Last, Sokoto, pp. 40-89.