Sources: Michelin Map 153, Yves Saint-Martin, L'Empire Toucouleur, 1848-1897, map on p. 78,

A. Kanya-Forstner, The Conquest of the Western Sudan, en map

Clarendon Press. Oxford. 1975. 239 pages

“… I found that Africans, like ignorant Europeans, are fond of talking about what they do not understand. These Negroes believed that Europeans live exclusively upon the water; that they have neither land, houses nor cattle; they added that the rivers and great waters belong to us, in the same manner as all the earth is their patrimony. I therefore concluded that this was the reason why white men alone were forced to pay imposts to the Negro kings, who regard them as their tributaries. They had not a high opinion of our courage, affirming that we did not even know how to fire a musket, and that this science belonged exclusively to the Moors and Pulas [Tokolor and Fulɓe].” 1

These remarks about Futanke attitudes, made by the explorer Mollien in 1818, could apply to most Senegambians at any time in the first half of the nineteenth century. The Africans observed that the Europeans did control the water, both the sea and the rivers, and lived essentially in coastal entrepots — Bathurst for the British, Goree and St. Louis for the French. They seldom disembarked from their boats to fight on land, the only kind of warfare the Africans knew and respected, and they were interested in trade rather than the “real” values of land, houses, and cattle 2.

Futa Toro was particularly well placed to demand “imposts” of the French Colony at St. Louis 3. It supplied much of the millet to feed the African population of the colonial capital and controlled access to the upper river valley, where lay much of the gum, gold, and other products of interest to the Europeans. The main channel was rather narrow, and boats could not escape the gunfire, arrows, and rocks projected from the banks. Shoals made navigation quite tricky, and grounded boats depended on the local residents to push them back into deeper water. If the inhabitants were hostile they could pillage the merchandise, kill the sailors, or simply let them wait for a St. Louis steamer to tug them loose. The currents and winds often forced the boatmen to pull the vessels up-river while walking in shallow water or along the bank. When the river was high, from July to December, the St. Louis government could protect the trade convoy with deep-draft ships armed with cannon, but even these vessels needed co-operation from the local people to obtain wood for fuel.

Like the Denyanke before them, the tooroɓɓe exploited their advantage by collecting a large duty each summer when the convoy came up-river. Futanke soldiers along the banks made sure the boats stopped at a place near the centre of the kingdom called Dirmbodya, which functioned as a “port of trade,” controlling contacts between Europeans and the state 4. There the representative of the French Governor sent a messenger to the Almamy's delegated authority, the Alcaty of Mbolo Biran. The Alcaty was carried to the shore in a canopied stretcher and received the payments: goods valued between 2,200 and 3,000 francs from the government and a duty from each boat according to tonnage 5. The Futankoobe often delayed the vessels for several weeks to force greater “generosity” from the traders and officials, who were loath to use their guns and cannons in most situations. The successful completion of the proceedings with the Alcaty theoretically guaranteed the security of the convoy in its journey up and then back down the river.

Most of the trading activity along the Senegal took place at escales or seasonal fairs 6. In the lower valley, navigable all the year round, the fairs corresponded with the gum harvests extending from January to June. Moorish clients and slaves did the painful work of cutting the resin off the trunks of thorny acacia trees found in “forests” north of the river. Zwaaya Moors guided the camel loads of gum down to the escales, negotiated the price and received their payment when the product was loaded on the boats. Hassani groups protected the caravans between forest and trade fair and, like the Almamy, received an annual duty in return. The transactions were supervised by a French gunboat and occurred at two escales controlled by the Trarza Moors, and one near Podor dominated by the Brakna group. The payments were made in guinées, a blue cloth serving as the most general currency in Mauritania and Senegambia. Imported from Europe and India, the guinée was a narrow strip of cloth about fifteen metres long. During the nineteenth century it had a value of thirteen to fifteen francs 7.

In the middle and upper valley the trading season corresponded with the high water 8. At several small escales the Futankoobe offered their millet in exchange for guinées, guns, powder, salt, and other items. The same markets often served as additional points of exchange with the interior traders (jula), primarily Soninke, who brought cattle and slaves to Futa and took the St. Louis goods back to the east and south. The inhabitants of the Upper Senegal peddled their wares at Bakel, where a French fort protected the operations. The principal product sought by the traders was once again gum, transported by the Idawaish Moors from the north, but there were also hides, a growing peanut production, and just enough gold to tempt the French to look for more.

Some traders and government officials also engaged in a thinly-disguised successor to the slave trade called rachat (ransom) 9. By this institution domestic slaves and recent captives were sold by their owners and became indentured servants in St. Louis families, trading-houses, or the small army of the French colonial government. The emancipation decreed in 1848 ended the already declining export of persons to the Americas but did not put an end to the local trade and demand. The decree also contained a clause affirming that any slave was “liberated” if he set foot upon “French soil”, defined as St. Louis, the river posts and any “annexed” area. For the rest of the century, local officials were hard pressed to limit the application of this principle in order to diminish the number of persons fleeing to St. Louis and to preserve good relations with the ruling and propertied classes of Senegambia.

The indentured servants formed about half of the 15,000 Africans living in the colonial capital in the mid-nineteenth century 10. They performed the most menial chores: domestic work, stevedores, deck hands in the river trade, messengers, delivery men, and soldiers. With time and effort they might move up to the rank of sergeant in the military, sous-traitant (sub-trader) or traitant (trader) in commerce or, if they could obtain French education, into a position of clerk or interpreter for the government 11. In the process they learned Wolof, began to practise Islam if they were not already Muslim, and suppressed the fact of their earlier captivity.

The free African population of St. Louis numbered about 6,000, and was largely Wolof and Muslim. In some cases they were descendants of indentured servants. They provided the bulk of the traitants who worked the river and the coast and thus spent several months each year at the escale to which they were assigned. Some financed their own operations and even competed with the major French firms, but most borrowed their guinees on credit from the big houses and conducted small-scale operations.

The rest of the St. Louis population was European in culture. There were several hundred persons of Eurafrican descent; they had some French education and were predominantly Catholic with European names 12. Some occupied management positions with the larger trading concerns while others worked in the French administration. Above them in the pecking order were the Europeans, a predominantly male community that had, over the decades and centuries, created the local mulatto population. Merchants and their dependents numbered about 200 and ran the big commercial houses, most of which were linked with Bordeaux. The colonial administration vacillated between 400 and 800 persons, and fell under the Paris Ministry of the Marine and Colonies. In addition to some civilian personnel, it included the officers and some of the enlisted men for the local infantry, cavalry, artillery, and government boats. The Europeans customarily left after a few years, happy to escape the heat and the white man's grave 13.

Until the 1850s the St. Louis government sought basically to maximize the short-term profits from the gum trade, thereby conforming to the perception of Europeans as traders living in boats and paying taxes to local chiefs. Efforts to create a plantation and settler economy had failed and there was little interest in the acquisition of land in itself 14. Between 1817 and 1854, thirty men served thirty-three terms is Acting or Titular Governor, correlating strikingly with the rate of turnover in the Almamate of Futa 15. This meant that the French and Senegalese commercial community provided the essential continuity and knowledge of the local situation, and tended to be extremely influential in the decisions made in Paris. In general, they favoured a conciliatory policy, but in the mid-nineteenth century internal strife and pressures were diminishing their trade revenues. In this context the merchants and traitants urged the Ministry to appoint an aggressive governor for several years with sufficient funds to “bring order back to the river”.

Paris granted the request in 1854 with the appointment of Louis Léon César Faidherbe, who lived up to his name and became the “Caesar” of French Senegal. Faidherbe had spent several years in Algeria and used this experience to lay the foundations for the future colonial territory in the form of boundaries, military and civilian organization, and policy towards Islam. He fundamentally changed the image of the European from trader to soldier and governor, and such was his impact that subsequent generations of Senegalese have remembered him as the “only governor” of the nineteenth century 16.

Alongside his well-known military expansion, Faidherbe reformed the French administration and its relations with the indigenous Wolof along the coast 17. He gave the local African troops a new esprit de corps and a new name, Tirailleurs Sénégalais (Senegalese Riflemen), and made them into an effective fighting unit instrumental in the later conquest of the Western Sudan, Dahomey, and Equatorial Africa. By creating a school for the “sons of chiefs and interpreters”, he found a way to train the personnel necessary for an expanding administration, and he made the Political Affairs Bureau into an effective source of information about the interior. His most important achievement was of a subtler sort: the development of a prestigious francophile Muslim community and tradition that persist in Senegal to this day. He formed a tribunal to handle most of the offences committed by the local Muslim population of St. Louis, made extensive use of his knowledge of Arabic and Islam in diplomacy, and sent two Senegalese on the pilgrimage to Mecca. The willingness of these influential “pilgrims” to accept and advocate French rule for Muslims was a critical dimension of St. Louis policy during the confrontation with another pilgrim, Umar Tal.

One striking aspect of Senegalese recollections of the nineteenth century is the way in which Faidherbe and his contemporary and rival, Umar Tal, have been singled out as prototypes. Where the Governor has become the symbol of French expansion, Umar has emerged as the archetype of Senegalese resistance and a kind of indigenous expansion. According to one story,

Faidherbe was born in Mecca of a French merchant and an Arab woman. He studied for a long time at the great mosque. It was in Mecca that he became embroiled with al-hajj Umar. Consequently his actions are an acceptable expression of the divine will 18.

Another tradition, postulating an encounter between Umar and Faidherbe which never in fact occurred, had it that

Umar went to St. Louis and stayed three days on the square opposite the Governor's palace. Allah had revealed to him the importance of going to St. Louis in order for things to go well for him. Umar saw Faidherbe who asked the purpose of his trip. Umar replied that he wanted to wage the jihaad. Faidherbe responded in a clear Arabic: — Don't you know that you need money to wage a jihaad? — Allah has commanded me to wage the jihaad, answered Umar. He will provide what is necessary. I must be free [of such concerns] in order to fulfill my mission 19.

Umar began his career rather inauspiciously in Western Futa Toro 20. He belonged to an undistinguished tooroɓɓe family and was born in the 1790s near Podor. As a youth, he pursued the normal course of studies and became a pupil of clerics belonging to a new branch of Islam called the Tijaniyya, named for an Algerian reformer of the eighteenth century.

In the 1820s he set out on the hajj or pilgrimage to Mecca, a feat exceedingly rare for Senegambians of his time, which immediately set Umar apart from other Muslim leaders of his generation. In the Near East he confronted disparaging attitudes towards black Muslims, but soon established his credentials as a scholar and miracle-worker. Before he left for West Africa he was named khaliifa or chief agent for the spread of the Tijaniyya order in the Sudan 21. This new “Way” of Islam stressed the close relation between the founder and Muhammad the Prophet, thereby short-circuiting for its members the various chains of spiritual authority built up by the older orders over the centuries. Umar's appointment was accompanied by messages from the founder and the Prophet and seemed, at least to those who became his followers, to give him an authority unmatched by any other West African cleric.

Umar used the journey to and from Mecca as a way of visiting all of the principal Muslim states created by reform movements in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: Futa Jalon, Masina, and the Sokoto Caliphate of Northern Nigeria 22. He lingered especially in Sokoto and made a strong impression on Muhammad Bello. In return for assistance in several military campaigns, he received Bello's daughter and one other woman as wives. Around 1840 he settled on land provided by the Almamy of Futa Jalon and in 1845 completed Rimaah, his major work 23. This manuscript described the Tijaniyya and the pilgrimage and helped establish Umar's authority as a reformer and chief Tijani representative in the Western Sudan.

The new pilgrim's prestige was widely recognized by his contemporaries. One who hoped to imitate the journey of Umar was Bu El Mogdad, a Wolof from St. Louis who helped Faidherbe create the francophile Islamic tradition. In making the case for his own pilgrimage, which he actually accomplished with French support in 1860-1, Bu El Mogdad wrote the Political Affairs Director about

how important it is in this country for any man who wishes to do either good or evil to possess authority; this authority is achieved by enjoying superiority over one's companions.

Al-Hajj Umar is an example of this. He was only an unknown inhabitant of Alwar who, having been expelled by his own people [not confirmed in other accounts], profited from the bit of Arabic he knew to undertake the pilgrimage to Mecca; it was this journey which allowed him subsequently to play such an important role. During his travels he perfected his Arabic, became learned in the Koran, and read a large number of good books. Having thus become the most learned of all his compatriots he was able on his return to set up as a Master and to interpret the Koran in his own way. If some noted marabout [cleric] raises an objection he always silences him by saying, “You have not seen what I have seen; I have visited the cradle of Islam for myself and read books unknown on the banks of the Senegal.” Sensible people who did not believe in Al-Hajj were overwhelmed by the dominant position which his own merits gave him; they were dragged along by the crowd of ignorant people who regarded him as a demi-god 24.

By the late 1840s, Umar had clearly become a well-known and controversial teacher and began to move into a phase of more active preaching and recruitment. In 1846-7 he finally returned to his own country and attracted several of the men who later served as his chief lieutenants. During this journey he had some inconclusive but generally friendly conversations with French officials, and shortly thereafter began to purchase guns and powder from the traitants of the Upper Senegal and from British sources based in Freetown 25. By 1849 he had already acquired sufficient following and arms to arouse the concern of his host in Futa Jalon, and he moved further east to a spot called Dingiray.

In 1852 Umar began his “jihaad of the sword” and by 1854 he controlled most of the watershed of the Senegal down to the Bakel fort. Although he considered himself the “Differentiator” who distinguished right from wrong and marshalled the believers against the unbelievers, his movement quickly developed an ethnic bias which did not correlate entirely with religious practice 26. The supporters were primarily Fulɓe and Tokolor drawn from Futa Jalon, Bundu, and especially Futa Toro, while the enemies consisted largely of the Mande-speaking peoples: Bambara, Mandinka, Khassonke, and Soninke. In their effort to undermine Umarian strength, the French later reversed the equation, forming a Mande alliance against the “Pular speakers”.

Although Umar did not return to Futa Toro between 1847 and 1858, he exerted enormous influence over the life of its citizens. His envoys always succeeded in finding recruits to join the campaigns in the upper valley, forming a new fedde or age-grade of those willing to “break ties with mother and father”. In preference to al-haajj or “pilgrim”, most of the new followers preferred to call their leader Sheku (the Pular equivalent of Shaykh, meaning “respected elder” in Arabic), a title ordinarily reserved for the zwaaya clerics who were considered superior to the local teachers 27. The new Sheku had established his equality in learning and spiritual power with the best that West Africa could offer. He was, indeed, the kind of reformer that the tooroɓɓe chiefs wished to exclude, but his challenge was too strong and was couched in terms of their own heritage.

His message to Futa had two basic components 28.

The trading season of Futa began innocently enough in the summer of 1853 30. The Almamy was Rasin Ndiatch, an opponent of the Wan and the candidate of the ageing but influential Eliman of Rindiaw, Falil. Before allowing the convoy to go up-river, the Alcaty renegotiated the customs duty and sent several sons of chiefs to St. Louis as “hostages” or security, including a member of the Rindiaw family. Rasin and Falil did not get their anticipated share of the trade revenues, which the Alcaty continued to channel to the Wan, and they began to lose some of the support they had previously enjoyed. In December the rumour spread that the French planned to challenge the regime by building a fort at Podor, and later that month the Governor's representative met secretly with two leading members of the electoral council. He persuaded them not to oppose the project, and neither signed any of the subsequent letters of complaint written by the Almamy and his counsellors to the Governor 31.

In January 1854, a new problem arose for the Almamy. A traitant named Malivoire ventured into Eastern Futa without the protection afforded by the convoy 32. When his boat was stopped near Kanel, the village belonging to the junior branch of the Wan family, Malivoire tried to protect his wares and was shot and killed in the process. In the ensuing panic all his merchandise was taken or lost, and St. Louis wasted no time demanding compensation and the delivery of the assassin. The tooroɓɓe chiefs put the blame on Mamadu Hamat Wan, second cousin and brother-in-law of Mamadu Biran of Mbumba, but could not agree on his fate. Rasin and Falil wanted to hand him over but others protested and nothing was done.

The French now had the Futanke leaders on the defensive. They could exercise leverage over Falil through the hostages and had made a deal with two other electors. The Alcaty was withholding revenues from the reigning Almamy and the Malivoire affair undermined the opposition to the Podor plan. It was the perfect time to move, and in March Governor Protet led about 2,000 troops to Western Futa to begin construction of the fort. By May the building was complete 33. Since Rasin had not prevented European intrusion into Muslim territory, and failed even to obtain payment for the land at Podor, he was deposed.

In May the electors named Mamadu Biran Almamy and gave him the unenviable task of solving the Malivoire and Podor problems. The French immediately added another challenge. In an effort to free an officer captured near Podor, a large colonial force assaulted and razed Dialmatch, a large jeeri village which had a reputation of impregnability and served as a refuge for political exiles in Western Futa. Although the officer was not found and the French suffered many casualties, they had proved they could fight on land and penetrate inland to the highlands 34. The pressure to retaliate was now immense and the Almamy moved his own forces into Toro province, both to control the Futankoobe and to menace the Europeans.

During the summer months Mamadu Biran and the electors faced a tremendous dilemma 35. They wanted to avoid any large military confrontation, and to that end secured the release of the French officer and sent the Alcaty to Podor to keep channels of communication open. The Almamy could not, however, afford to hand over his cousin to St. Louis and had to obtain some results on the other burning issues : the return of the hostages and, above all, compensation and rent for the fort of Podor. Mamadu insisted that Protet come to negotiate with him while the Governor demanded the surrender of the alleged assassin before treating other questions.

The impasse stretched on into the autumn. The Almamy was losing his control over the Futankoobe, who increasingly interrupted the gum and millet trade of Podor. The Commandant of the fort created satellite villages in the adjacent area and obliged the inhabitants to pay taxes, another encroachment on the sovereignty of the country and the independence of Muslims from non-Muslim authority. At this point, the chief lieutenant of Sheku Umar arrived to enlist recruits for the campaigns of the Upper Senegal. He was Alfa Umar Wan from Kanel, cousin to both the alleged murderer and the reigning Almamy, and he proposed the only honourable way to avoid confrontation with the Europeans : consultation with the Sheku and participation in the Umarian jihaad 36.

Consequently Almamy Mamadu, many of the chiefs and 3,000 Futankoobe set out in November 1854 to meet Umar in Farbanna, 300 miles away. Of the electors only Falil Atch was missing, and it was the largest and most illustrious catch that Umar had yet made. The “consultation” in the Upper Senegal left little doubt that the pilgrim reformer had become the effective Almamy of Futa and its highest court of appeal. In the words of two Saint Louisian observers concerned about the “Umarian menace”,

… [Some of the chiefs] explained to Al-Hajji that Mamadu Hamat had put to death in blatant fashion a Senegalese [i.e. Saint Louisian, viz. Malivoire], that their children were held hostage in St. Louis where the Europeans could justifiably kill them since the Almamy refused to hand over the murderer.

— Judge between the Almamy and us, they said. Should we not give satisfaction to the Europeans ?

Al-Hajji answered them:

— I told you before that you would come to me. I already knew about the affair. I cannot make a decision about it right now. The time for that will be when I return to Futa. Right now it is more urgent to work for the conversion of the unbelievers. You will thus accompany me in the war I'm undertaking against Karta. On my return, Futa will see me and know my decision. Mamadu, the one you call Almamy, will return to your country. He is no longer Almamy, but my Alfa (Lieutenant). He will administer Futa until the end of the war [in Karta], having as his auxiliary Eliman Mbolo, responsible as the Alcaty for receiving the duty paid by the Europeans. Mamadu, as my Alfa, and during my absence, you will abstain from eating meat and will not leave your house … 37

While the alleged assassin and most of the Futankoobe joined in the Kartan campaign, “Alfa” Mamadu returned to the middle valley to “wait” for Umar to come. The reformer did finally come, four years later, but the Alcaty never again received the customs from St. Louis, for Protet and Faidherbe transformed French relations with Futa.

During 1854 the relations between the French and Umar shifted from a posture of neutrality to one of open hostility 38. By that summer the Tokolor leader had control of most of the upper valley and the trade going to Bakel and the nearby escales. Umar still expected to purchase guns and ammunition from the traitants and wrote Protet to that effect. When it became apparent by the end of the year that the French had no intention of selling weapons to him and, in fact, were arming his Mande foes, he retaliated by confiscating the merchandise along the river and voiced his anger in a letter to the inhabitants of St. Louis :

“If you ask me why I confiscated the merchandise of the Christians, it's because of the wrongs that the Christians have done to me. In the first place, they declared that they would sell me neither arms nor munitions. They did that not knowing that I have no need of them. When the envoy of your tyrant [the Governor] came to me, [I tried to explain matters to him]…39”

The French were now intent upon strengthening their position in the upper valley at the expense of Umar. In addition to the discriminatory arms policy, they reinforced their garrisons at Bakel and Senudebu in the fall of 1854 and, as soon as the gunboats could steam up the river in 1855, embarked on an expansionist policy designed to displace their rival. The centrepiece of the new plan was an arrangement made with Sambala, a member of the royal family of Khasso. In return for support of his candidacy against an Umarian opponent, Sambala allowed the French to construct a new fort at Medine. Faidherbe also signed treaties with several Mande-speaking chiefs, began to recruit Mande workers and soldiers, encouraged Umarian slaves and followers to defect and contacted the Bambara of Segu 40.

To complete this network of alliances the Governor needed an ally in Bundu, the kingdom which lay along the left bank of the Upper Senegal at the crossroads of north-south and east-west routes 41. The Sy dynasty had established its hegemony in the area in the late seventeenth century and repeatedly used its strategic location between the Senegal and Gambia rivers in negotiations with Europeans. By and large they favoured trade down the Senegal to the advantage of the French, but on occasion they sent goods overland to the British ports in the Upper Gambia. After intervening in Futa in the downfall of Abdul Kader, Bundu joined in a rather firm alliance with St. Louis beginning in the 1820s. Almamy Sada even allowed construction of a fort at Senudebu in the 1840s. In 1852, however, Sada died and a succession struggle ensued. Umar's influence grew until he became, as in Futa Toro, the dominant force.

In the summer of 1855 Faidherbe found his ally in the person of Bokar, son of Sada 42. Bokar had joined Umar's campaigns along with several other Sy, but quickly became disillusioned after the execution of some of his relatives from the royal family of Karta. He managed to escape and return to Bundu, where he quickly formed an alliance with the French to take the kingdom away from an Umarian rival. Early in 1856 Bokar and the Bakel Commandant began to take the offensive and by the end of 1857 the balance of power had shifted in their favour. The collaboration was formalized in a treaty of friendship in 1858, whereupon Almamy Bokar Sada served as the linchpin of French strategy in the Upper Senegal until 1885.

Meanwhile, Umar met prolonged resistance in Karta and did not master the situation until the end of 1856. By this time the initiative in the upper valley had passed to the French. They threatened to divide the Tokolor conquests into a Kartan sphere in the north and a Futa Jalon section in the south and to cut the Sheku off from needed reinforcements from Senegambia. Under heavy pressure from his lieutenants, Umar openly challenged the French for the first and last time in April of 1857 by attacking Medine, the symbol of the new aggressive European policy. The reform forces razed the countryside and drove Sambala into the fort, where a Eurafrican named Paul Holle was in command. When the assault against the cannons failed, the Umarians laid a siege which quickly assumed the proportions of an epoch-making conflict. In the words of the President of the Imperial Court in St. Louis,

“During the next few days the al-hajjists showed themselves in large numbers. By day they remained beyond the range of the cannons, but at night they crept forward along the rocks to the fort. One could hear not only their voices, one could even understand the words: “Al-hajji, call your friends in Nioro, Futa, Bundu and Gidimakha! God is great, he is for us. Muhammad is the true Prophet of God, the last to come. He will give us the victory!”

Paul Holle, impatient with the cries of the multitude, wanted to make him [Umar] understand the futility of these threats and placed over the gate a sign on which was written the following: “Long live Jesus !!! Long live the Emperor [Napoleon III] !!! Conquer or die for God and the Emperor!!!” 43

In late July the rising waters of the Senegal permitted Faidherbe to lift the blockade and rescue the famished garrison and its refugees. The Governor then took the offensive against Umar, driving him further up-river. His armies suffered enormous losses at Medine and in the other engagements: together with large-scale desertions, the Umarians were reduced from over 15,000 to about 7,000 troops 44. The experience confirmed the Tokolor leader in his predilection for covert opposition to the Europeans and strengthened his resolve to establish his hegemony further east. Faidherbe had proved, at least for the moment, his ability to control Senegambia.

In the middle valley the two protagonists had not been idle after the crises of Malivoire and Podor. Umarian envoys moved easily through the country and brought substantial numbers of recruits to the campaigns in Karta and Khasso in 1855-7. For his part, Faidherbe outlined in October of 1855 an “understanding of relationships with the Futa” which was to guide his actions for the next few years 44. The plan called for additional posts in the centre at Salde and in the east at Matam, gunboats at the smaller escales, prompt reparations for all damages to commerce, and continued use of sons of the nobility as hostages. It was designed to “dismember” or reduce Futa to a “manageable” level of size and power.

Initially the French sought simply to maintain access to the upper river and combat Umarian recruitment. The Podor Commandant, as the only officer permanently stationed within the middle valley, took the leading role. In a public demonstration in 1855 he shot an agent and relative of the Sheku, while in the following year he began offering special inducements to the Mande-speaking slaves of Toro to flee their masters and join the French army, on the assumption that their hatred for the Tokolor would make them reliable soldiers 45.

Faidherbe chose the fort at Matam as his first major innovation, and as a means to strengthen French influence in the areas closest to Umar. As Protet had done in the Podor case, he combined diplomacy with force and began in the fall of 1856 to make overtures to the resilient politician from Mbumba, Mamadu Biran. After his return as the “lieutenant” of Umar, Mamadu had confined his activities to the village until 1856, when he successfully pushed his candidacy for the Almamyship. In his early correspondence with the Governor, the Wan leader requested the restoration of the annual customs which had lapsed since 1853. Then, caught between pressures from the Umarian envoys and a show of French force near Podor, Mamadu decided to cast his lot with Faidherbe. In a letter written to the Governor in the summer of 1857, he declared:

I wish only for what will produce good relations between our countries, because it is in my interest. I want only peace and tranquillity. I wish for everything that you wish for and repudiate all that you repudiate. As long as you are Governor of Senegal and I am Almamy of Futa, I will be of the same mind. I am not asking and will not ask for the customs. All I seek is to be right with you, and all of my people desire the same thing. We have the same interests 46.

With the high water in July 1857, Faidherbe was ready to move 47. While most of the convoy went upstream to relieve Medine, some soldiers and boats stayed at Matam to start the building of the new fort. The justification was the series of raids on the traitants for which there had been no compensation. As with Podor, the Governor offered no payment for the site and bombarded the villages that harassed the construction and trade. The Futankoobe were too disunited to resist effectively and Almamy Mamadu limited his actions to formal letters urging the French to desist.

To preserve his position, Mamadu had to put in an appearance and arrived in Eastern Futa early in 1858. In February he joined the partisans of Umar in placing a barrier of stones, sticks, and tree-trunks across the river at Garii, a few miles above Matam. The idea was ostensibly to prevent the boats from going to the upper valley during the coming high-water season, but the dam was abandoned in April and washed away by currents in July. Mamadu found the barrier a useful way to divert Futanke energies from Matam itself 48.

Just as the waters began to rise to permit Faidherbe to operate in the Upper Senegal, Sheku Umar marched down river into the heart of Futa Toro. The reformer had recovered much of the following and territory lost the year before, and his bold move seemed to presage an even more violent conflict than Medine. Such a struggle was averted, however, and this was primarily because the two sides had potentially compatible objectives and because each leader controlled his followers. For Umar, the goal was recruits for the campaigns in the east where he had established the new and “true Almamate”. For Faidherbe, the aim was to set up gold-mining operations at Kenieba in the upper valley.

Kenieba represented the culmination of the Governor's expansionist policy and was intended to rationalize and increase greatly the extraction of the precious metal that had long whetted the appetites of Europeans along the coast 49. To insure its success, Faidherbe instructed his officers at Podor and Matam to remain in their posts and take absolutely no initiative which might provoke Umar or force him to rush back to the east. He established a protectorate over Dimar province and sent special contingents to keep watch along the western border of Futa and help protect the Lower Senegal and the heartland of the Colony 50. Having established the priorities and taken precautions, Faidherbe felt secure enough to go on a leave of absence in France between September 1858 and February 1859.

Umar's presence shook Futa Toro to its foundations, creating a dividing line of “before and after” that still marks the memories and oral tradition of its inhabitants 51. The Sheku spent June travelling through Eastern Futa and arrived in July at Hore-Fonde, where he established his headquarters for the next six months. The choice of the ceremonial capital of Futa meant that Mamadu Biran had been deposed and that Umar was now the effective Almamy. He collected the assakal and other fees that customarily went to the provincial and central authorities, and renewed his criticism of Futa's stewardship of its Islamic heritage. He did not have to look far for illustrative material for his sermons : the posts at Podor and Matam, constructed without permission, compensation or rent, and the elimination of the annual duty which described the proper relationship of European traders to Muslim rulers. His message was simple, and rang out again and again that year in Futa:

« True friends, emigrate. This country has ceased to be yours. It is the country of the European, cohabitation with him is not suitable for you 52.»

Where in an earlier day Umar had recruited soldiers for specific campaigns, now he was calling for a permanent movement of families and flocks to a new home in the east.

The reformer did encounter opposition, including a few open challenges to his authority early in his stay. In late August these opponents, largely tooroɓɓe and noble Fulɓe from the central provinces, succeeded in briefly forcing Umar out of Hore-Fonde. The principal spokesman against migration was the aged but respected elector from Rindiaw. Falil is reported as saying, “Leave us now, for each who wishes will certainly come with you, and each who doesn't will stay. He who goes will, upon returning, find us here.” Umar asked if he [Falil] spoke for them, and they said he spoke for all 52. But the personality of the Sheku and the pressure of his numerous following were too powerful. By November all open opposition ceased and Falil himself embarked in a large caravan headed for Karta. Of those who stayed, Umar persuaded many not to plant the waalo millet, which meant they were almost certain to emigrate with him later in the year 53.

Covert opposition continued throughout the dry season, instigated primarily by the Central Futa chiefs who resented the reformist challenge of a man from an obscure family of Toro province. They wrote frequently to the French to send an army but received only verbal expressions of support. The man in the most difficult dilemma was Mamadu Biran. Given his prominence and his close ties with the Wan of Kanel, who by and large supported the Umarian cause, the ex-Almamy was a natural target for recruitment. Displaying his habitual resourcefulness, however, he shifted his place of residence several times to avoid confrontation, sent many of his slaves to Matam and St. Louis for safe keeping, and survived the “year of Umar” without leaving his homeland or losing his wealth 54.

In January 1859, Umar left Hore-Fonde to tour his native province 55. There virtually everyone embraced his cause. Many had obeyed the injunction against planting and were ready to depart, while others needed pressure in the form of burned granaries or compounds. In late February the preaching and recruitment came to a rather abrupt halt when news of three developments reached the Umarian camp: Faidherbe had returned to St. Louis and was coming to Podor, the Bambara were planning a counter-offensive in Karta, and the electors of Central Futa had chosen a new Almamy to mobilize resistance to migration 56.

In response, the Sheku marshalled his considerable forces and began an impressive sweep up-river. The new chief of state and the other “conspirators” took refuge on the north bank and the only skirmish was an inconclusive exchange of gunfire with the Matam fort. In mid-May, swollen by recruits from Eastern Futa, the Umarian procession left the middle valley en route to Karta.

The migration, or Fergo Umar as it is called in Futa, had netted another illustrious catch, including recruits from all of the provinces and probably most of the influential tooroɓɓe, seBBe and noble Fulɓe families. Among the leaders known to have left were Falil Atch, the venerable Rindiaw elector; Mamadu Mamudu Kan of Dabiya, elector and grandson of Ali Dundu; Sada Kan of the family of the Alcaty; Hamat Sal, Lam Toro or chief of Toro province; an important cleric from Hore-Fonde; several tax-collectors from the central and eastern provinces 57. Each chief took his particular entourage of family, slaves, and clients.

The size of the Fergo was staggering. The Bakel Commandant estimated that the caravan passing near his fort in May contained 40,000 people, and Faidherbe later observed that the population of Eastern Futa and the Upper Senegal had been reduced by half, whether by migration or death 58. Central Futa was only in relatively better shape, as the Governor reminded its leaders in 1860:

“Your country is depopulated and ruined. It's no longer a country but a desert. If everyone isn't dead of hunger, it's thanks to us.” 59.

It is reasonable to estimate the total departures from Futa for 1858-9, coupled with the earlier migration in the 1850s, at over 50,000 men, women and children, or almost 20 per cent of the population. The percentages for Eastern and Western Futa were higher, since the chiefs of the central region were better able to protect their fields and keep their followers.

The effects of emigration and the widely obeyed injunctions against growing new crops were more serious than even these figures suggest. Until 1861-2 there is scarcely a word of a good harvest or trading season. Famine and raiding were widespread. In February 1859 the Commandant of Matam reported that five or six people were being buried every day in the small village next to the fort, and in the summers of 1858 and 1859 bodies were seen strewn along the roads of Eastern Futa and the upper valley. Most of the inhabitants of the Ferlo abandoned their villages to accompany Umar, creating problems for the control and maintenance of pasture lands and wells, while in Futa many fields lay vacant, diminishing the crops and opening the way to land disputes 60.

After leaving Futa in 1859 Umar concentrated his energies further east. In 1860 he worked out an understanding with St. Louis whereby each side recognized the sphere of influence of the other — the French in Senegambia, the Tokolor in the area of modern Mali. The Sheku reasserted his control over Karta, conquered Segu and Masina and even extended his influence as far as Timbuktu before a revolt took his life in 1864. The Umarian forces soon re-established control over the vast domains that constituted the Tokolor Caliphate and Amadu Sheku, eldest son and appointed heir of the reformer, assumed the title of Laam Julɓe or “Commander of the Faithful” 61 Amadu reigned with varying degrees of success until the French conquest in 1890-1. Although he chose Segu as his principal residence, the inhabitants of Futa Toro continued to call the entire Umarian state “Nioro”, the name of the temporary headquarters in Karta in the 1850s.

Sheku Umar made an enormous impact on his native land during his lifetime and afterwards, under the reign of Amadu Sheku. He had superseded Abdul Kader as the great religious and political leader and remained the “real” Almamy for many Futankoobe. His message of purification and emigration was followed by subsequent reformers and the state which he created in Karta and Segu became a model and a kind of spiritual home for Pular-speaking people. Migration to “Nioro” continued until the French conquest of the Umarian state in 1890-1. In fact Fergo Umar or Fergo Nioro became both a substitute pilgrimage and an imitation of Muhammad's hijra (departure) to an area where Muslims could rule themselves 62. The Meccan hajj was extremely arduous, while the journey from Senegambia to the new Caliphate involved 300-500 miles along relatively secure routes. As hijra the journey implied leaving an area that was now “polluted” by European influence and control. The Futankoobe and others also migrated for more mundane reasons, such as the desire for material gain, enhanced status, and power. Some returned to Futa and used their new credentials to improve their situation. Migration tended to increase either in response to Amadu Sheku's needs and appeals, as when “Nioro” was threatened or wanted to undertake a major campaign, or when conditions in the middle valley became difficult. This might mean bad harvests or an epidemic, arbitrary acts of a chief, the extension of European control in the form of new taxes or the emancipation of slaves, or some combination of these. The migrants also moved in the opposite direction when material, military, or ideological problems arose in the east. (See Appendix IV for a chronology of major movements of people between Futa and “Nioro” in the late nineteenth century, as reflected in French archives.) 63.

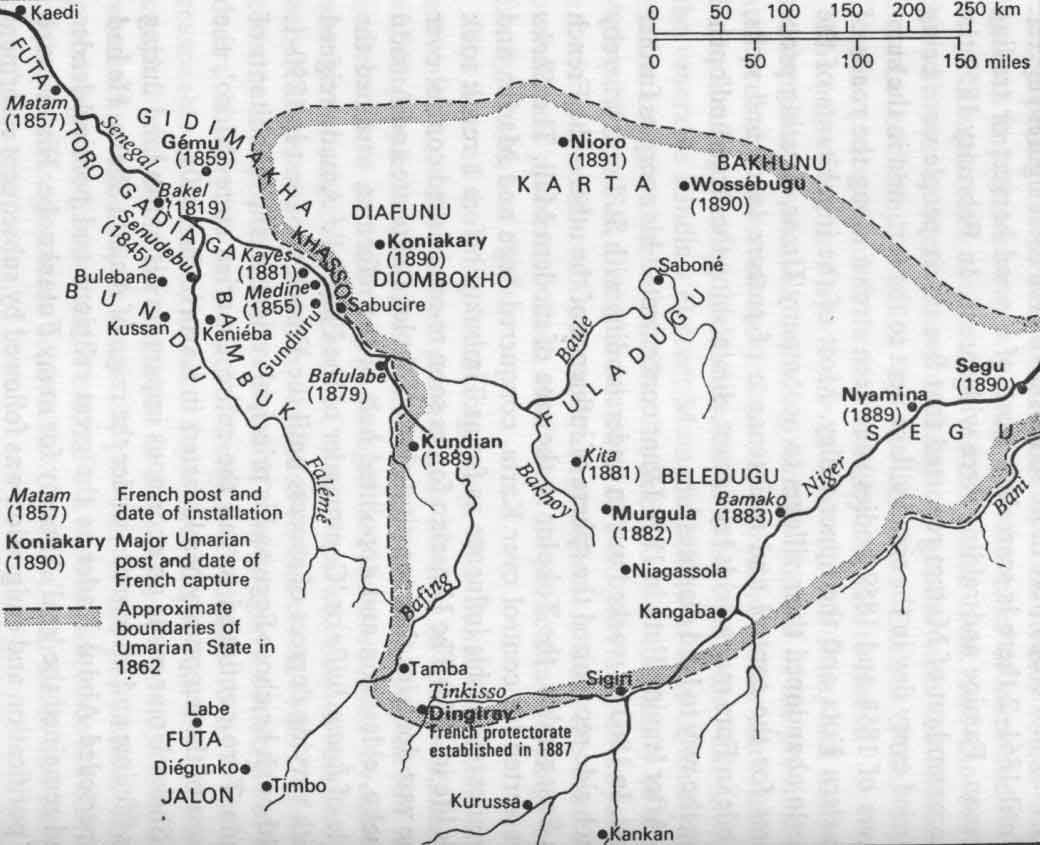

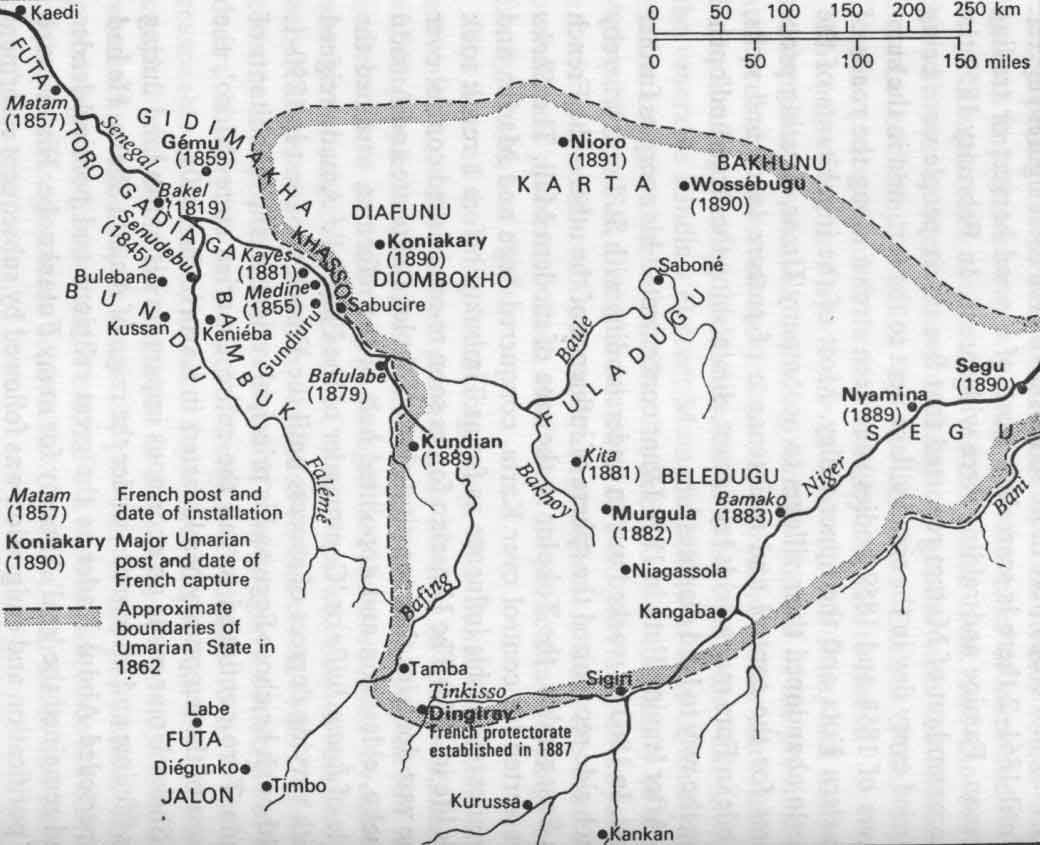

Map IV. The Umarian State in relation to Senegambia

Sources: Michelin Map 153, Yves Saint-Martin, L'Empire Toucouleur, 1848-1897, map on p. 78,

A. Kanya-Forstner, The Conquest of the Western Sudan, en map

In the wake of the Umarian exodus St. Louis took advantage of Futa's weakness to establish protectorates in the eastern and western extremities to consolidate the process of “dismemberment”. The protectorate was an inexpensive form of administration involving French suzerainty, in the form of a local garrison and Commandant, and some local autonomy. The indigenous chief agreed to encourage trade and respect the rights of French subjects in his areas. In theory, local leaders elected the chief and he ruled according to custom. In reality the French appointed the chief and he took advantage of his “protection” to make new demands of the population. He usually came from a lineage whose authority had been reduced by the tooroɓɓe regime and who might be favourably disposed to collaborating with the European power against the Almamy and Central Futa 64. In April 1859 the French signed a treaty with the principal leaders of Toro which recognized the independence of the province from the Almamate and set out its obligation to refuse asylum to enemies of St. Louis 65. The choice of its chief, the Lam Toro, was controlled by the Podor Commandant, and in the “elections” Hamady Bokar Sal was picked because of his proven hostility towards Umar. In September 1859 the Governor sent his representatives to Eastern Futa to establish a similar protectorate, this time under the watchful eye of the Commandant of Matam 66. The chief was to come from the Any or Elfeki lineage, formerly clerical advisers to the Denyanke regime.

At the same time, the French sought to extend their influence in Central Futa 67. In August they purchased land not far from the spot where previous governors had paid the annual customs, and constructed the third post in Futa under the name of Salde. They then pressured Almamy Mustafa to accept in writing the loss of Western and Eastern Futa. Mustafa refused and the two sides agreed only on a treaty recognizing the Almamy's rights and responsibilities towards trade in the central region.

The Governor then made a special trip to Mbumba to see his ally of years past, Mamadu Biran. In return for Mamadu's verbal recognition of the 'dismemberment' of Futa, Faidherbe promised his support for the Wan leader's ultimate ambition in a 'confidential letter' written during the Mbumba meeting on 11 September 1859:

This is to inform you that if you faithfully execute the conditions of the treaty, we will work with you so that you may really be chosen chief and king of Futa, from Boki to Gaol [i.e. Central Futa], with no possibility of being deposed. This is the only means to restore order in the land and save Futa from the sad situation in which it finds itself.

Let this be a secret between you and me 68.

By the end of 1859 Mamadu had replaced Mustafa as Almamy of Futa and implicitly accepted the reduction of territory, and Paul Holle, the Governor's “trouble-shooter” at Medine and Matam, was brought to Salde to manage the new arrangements with the Wan “king” 69.

The “life term” was put in jeopardy, however, as French interests began to shift away from the river to western Senegal and Wolof country, where the cash crop of peanuts could be grown. The peanut, avidly sought by French industry as a source of vegetable oil, soon eclipsed the old staple of gum and gave modern Senegal a coastal rather than a riverine orientation. In October 1860 St. Louis ended a chapter of eastern expansion by dismantling the mining and processing equipment of Kenieba. The extraction of the fabled gold had proven too costly 70. Ironically, both of the principal contenders of the 1850s turned their attention away from Futa and the river as the decade ended, leaving it to other hands to try to pick up the pieces.

Notes

1. Mollien, Travels, p. 137.

2. For the Futankoobe, the European might “possess” the river, thanks to his gunboats, but not the “jeeri”. ANS 13G140.72 (no date, about October 1863); ANS 13G168.12 (24 December 1860). It was acceptable for Muslims to trade with the European, but not to cohabit with him. FR, Rasoulou Ly. Sec also J. D. Hargreaves. Prelude to the Partition of West Africa (London, 1963) (hereafter Prelude), pp.101-2.

3. The best description of the lower and middle valley of the river in the mid nineteenth century is Anne Raffenel, Voyage dans l'Afrique Occidentale (1843-44) (Paris, 1846) (hereafter Voyage), pp. 14-75.

4. For the “port of trade” or “administered trade” concept, see Karl Polanyi, C. Arensberg, and H. Pearson, eds.. Trade and Market In the Early Empires (New York, 1957), pp. 243-70 and passim.

5. For the ceremonies and duties at Dirmbodya, see ANS 2B24.403 (21 December 1844); 13G7, chapter 8 (Treaty of 1 September 1853); Moniteur du Sénégal et Dépendances (hereafter Moniteur), 2 August 1859 ; Saugnier and Brisson, Voyages, pp. 289 ff.

6. For the escales and the gum trade, see G. Désiré-Vuillemin, “Essai sur le gommier et le commerce de la gomme dans les escales du Sénégal” (Thèse secondaire, Montpellier, 1961), passim; Golbéry, Fragmens, I, pp. 206 ff.; Anne Raffenel. Nouveau voyage dans le pays des nègres (Paris, 1856) (hereafter Nouveau voyage), II, pp. 79-88 ; Stewart, Mauritania, pp. 120 ff.

7. For guinée values in the 1840s, see Stewart, Mauritania, p. 162.

8. For the interior trade, see Carrère and Holle, Sénégambie, p. 135; Raffenel, Nouveau voyage, pp.14-75.

9. François Renault, L'Abolition de l'esclavage au Sénégal (Paris, 1972) (hereafter Abolition), pp. 20 ff.

10. For the population of St. Louis, see Boilat, Esquisses, p. 207; and the Tableaux de population, de culture, de commerce et de navigation of 1843-62 and 1864-7, published by the Ministry of the Marine and Colonies. For portraits of St. Louis society see Boilat, Esquisses, pp. 206-27; G. W. Johnson, Jr., The Emergence of Black Politics in Senegal (Stanford, 1971) (hereafter Emergence), pp. 23-5.

11. The traitants and sous-traitants were registered and licensed and came below the marchands and négociants in the commercial pecking order. Some of these traders worked as far south as the Conakry area. Cf. Annuaire du Sénégal et Dépendances, 1860 (Paris, Ministère de la Marine et des Colonies), pp. 83-91; S. Amin, Le Monde des affaires sénégalais (Paris, 1969) (hereafter Monde), pp. 11-19.

12. The Eurafricans are often equated with the habitants, persons of at least partial African descent who possessed a certain social standing in St. Louis and the other ports. For some of the varying definitions of habitants, see the Boilat and Johnson references of note 1, above, and J. D. Hargreaves, “Assimilation in Eighteenth-Century Senegal”, JAH6.2 (1965), pp. 177-84.

13. 500 to 1,000 persons died each year in St. Louis in the 1840s and 1850s, including a disproportionate number of Europeans. See the Tableaux referred to on page 31, note 1.

14. For the earlier colonization efforts, see G. Hardy, La Mise en valeur du Sénégal de 1817 à 1854 (Paris, 1921), pp. 25 ff.

15. Annuaire du Sénégal et Dépendances, 1860, pp. 102-4.

16. There are a number of biographies and shorter accounts of Faidherbe: M. Brunel. Le Général Faidherbe (Paris, 1890); R. Delavignette, éd., Les Constructeurs de la France d'outre-mer (Paris, 1946); A. Demaison, Faidherbe (Paris, 1932); G. Hardy, Faidherbe (Paris, 1947) ; C.-A. Julien, éd. Les Techniciens de la colonisation (Paris, 1953); J. Riéthy, Histoire populaire de Faidherbe (Paris, 1901). Faidherbe has written his own account of Senegal and his career there, including events down through most of the 1880s (Le Sénégal. La France dans l'Afrique Occidentale, Paris, 1889), which repeats most of the publication authorized by the Ministry of the Marine and Colonies, Annales sénégalaises de 1854 à 1885, suivies des traités passés avec les indigènes (Paris, 1885) (hereafter Annales).

17. For Faidherbe's achievements, see this author's Master's Thesis, “Faidherbe, Senegal and Islam: a Discussion” (Columbia University, 1965) (hereafter “Faidherbe”), pp. 49 ff. ; J. Duval, “La Politique coloniale de la France”, Revue des Deux Mondes, October 1858, pp. 517-52, 837-79.

18. G. Hardy, Une Conquête morale (Paris, 1917), p. 304. According to one local tradition, Faidherbe had obtained amulets from a famous Diakhanke cleric named Soare and these enabled him to succeed. P. Smith, “Les Diakhanke”, Bulletin et Mémoires de la Société d'Anthropologie de Paris, 11th series, 8 (1965), p. 236. Faidherbe helped portray Umar as the great antagonist of the French. Cf. Y. Yves Saint-Martin, L'Empire Toucouleur, 1848-1897. Un Demi-siècle de relations diplomatiques 1846-93 (Dakar, 1967) (hereafter Relations), pp. 91-2.

19. FR, Amadou Wendou Node Ndiaye, session 3.

20. There are several summaries of Umar's life; J. Abun-Nasr, The Tijaniyya (London, 1965), pp. 106 ff.; B. G. Martin, “Notes sur l'origine de la Tariiqa des Tijaaniyya et sur les débuts d'Al-Haj 'Umar,” Revue des Études Islamiques, 1969, pp. 267-90; B. O. Oloruntimehin, The Segu Tukolor Empire (London, 1972) (hereafter Empire); and Yves Saint-Martin, L'Empire Toucouleur, 1848-1897 (Paris, 1970) (hereafter Empire); J. R. Willis, “Jihaad fii Sabiil-Allah. Its Doctrinal Basis in Islam and some Aspects of its Evolution in Nineteenth Century West Africa”, JAH 8.3 (1967), pp. 395-415 (hereafter “Jihaad”). For primary sources, I have drawn on FR, Amadou Wendou Node Ndiaye, sessions 1, 2, and 3; Thierno Malik Diallo, manuscript in Arabic on the life of Umar (constituting document 7 of the Fonds Curtin of IFAN, Dakar, and photographed initially in Kidira, Senegal) (hereafter “Diallo manuscript”); M. Delafosse, “Traditions historiques et légendaires du Soudan occidental”, Renseignements Coloniaux, 1913, pp. 293-6, 325-9, 355-69 (hereafter “Traditions”); E. A. Mage, Voyage dans Ie Soudan occidental (Vasis,, 1867) (hereafter Voyage), pp. 140-86; M. Sissoko, “Chroniques d'El Hadj Oumar et du Cheikh Tidiani”, Bulletin de l'Enseignement de l'A.O.F., 1936 (pp. 242-55), 1937 (pp. 5-22,127-48) (hereafter “Chroniques”); M. A. Tyam, La Vie d'El Hadji Omar: Qaçida en Poular (Paris, 1935, translated and edited by Gaden) (hereafter Qaçida).

21. The term khalifa or “successor” was applied both to the ruler of an Islamic state and to the leader of a Sufi or “mystical” order of Islam.

22. For the controversies surrounding the Tijaniyya and Umar's stay in Sokoto, see A. H. Ba and J. Daget, L'Empire Peul du Macina, I (Paris, 1962) (hereafter Macina), pp. 240 ff. ; Last, Sokoto, pp. 215-19.

23. The full title of the work was Rimaah Hizb al-Rahiim “alaa Nuhuur Hizb al-Rajiim, and it was published in the margin of 'Ali Harazim's Jawaahir al-Ma'anii (Cairo, 1927). For other works of Umar, see the articles of Martin and Willis cited on page 34, note 2, and J. Salenc, “La Vie d'Al Hadj 'Omar”, Bulletin du CEHSAOF, I (1918), pp. 405-35.

24. J. D. Hargreaves, éd., France and West Africa (London, 1969), pp. 148-9. Bu El Mogdad's account of his own pilgrimage can be found in “Voyage par terre entre cette colonie et le Maroc”, Revue Algérienne et Coloniale, 1 (1861), pp. 477-94. For résumés of the principal voyages accomplished by the French under Faidherbe, see J. Ancelle, Les Explorations an Sénégal et dans les contrées voisines (Paris, 1886) (hereafter Explorations).

25. For the 1846-7 visit to Futa, see Tyam, Qacida, pp. 24 ff. The only first-hand account of Umar's conversations with the French, to the best of my knowledge, is Holle's in Carrère and Holle, Sénégambie, p. 195. For a letter written by Umar to the Governor and Political Director and received in St. Louis 25 June 1847, see ANS13G139.16.

26. Faaruugu, Pular version of the Arabic al-faaruuq, (he who distinguishes truth from falsehood). It was an epithet of the second Caliph or khaliifa after Muhammad, who was also named Umar. Tyam, Qacida, pp. 232 and passim. According to Islamic doctrine, the legitimacy of the military phase of the jihaad depended upon prior efforts to purify oneself and to persuade non-Muslims to change, efforts which Umar had been making before 1852. Willis, “Jihaad”,pp. 398 ff.

27. For the use of fedde, see Tyam, Qacida, passim. For the use of Sheku and the superior learning attributed to Umar, see FR, Mamadou Dia, session 2; FR, Amadou Wendou Node Ndiaye, session 2; Ba and Daget, Macina, I, pp. 233 ff.

28. FR, Al-Hadji Ismaila Sam, session 4 (passages of Hamady Sayande Ndiaye); Kamara, Zuhuur, II, ff. 296-7; and the sources mentioned in note 1, above. For the impression which Umar made on Senegambians in general at mid-century, see Carrere and Holle, Sénégambie, pp. 194-207; Hargreaves, Prelude, pp. 101-2.

29. According to one tradition, Umar was born as the Futankoobe were marching towards the battle of Bunguye (1796). FR, Thierno Yaya Sy, session 2; Kamara, Zuhuur, II, f. 294. For the desire for revenge against the Bambara, see Samb, 'Omar par Kamara', pp. 804-18.

30. The toll paid by the administration at mid-century amounted to about 2,215 francs. Individual boats weighing over sixty tons paid 1,431 francs and others proportionately less according to weight. ANF, OM SEN.1.46a (13 October 1859). For the events of the fall and the hostility between Falil and the Wan, see ANS 5B14 (25 January 1849); ANS 13G33.1.25 (10 June and 10 July 1853); ANS 13G139.83.

31. The electors were Bokar Ali Dundu, father of Abdul Bokar, and Alfa Ali Sidi Ba. See ANS13G139.85-6.

32. The village where the incident occurred was Nganno, where Mamadu Hamat Wan was the headman. For the event and the Wan of the Kanel area, see ANS 5B14(11 March 1854); ANS 13G139.87; Kamara, Zuhuur, II, ff. 184-5.

33. The account of the Podor expedition is contained in ANS 5B14 (11 March 1854); ANS 13G33.1.27 (2 March 1854); ANS 13G139.88-9; Annales, pp. 1-4. The medical and some military aspects of the expedition are covered in “Relation médicale de l'expédition de Podor”, Revue Coloniale, 15 (1856), pp. 456-504.

34. The French suffered 175 casualties at Dialmatch, including fifteen deaths. Others died later as a result of wounds. ANS 13G117.216; ANS 13G120.1-5; “Relation médicale”, cited in note 1, above.

35. ANS 2B31bis (1 January 1855); ANS 3B66.20, 25-6; ANS 13G120.23-7; ANS 13G 139.92. Governor Protet considered an attack on Abdallah, the Wan base on the river, but abandoned it because the water level in the river was falling rapidly. ANS 2B31 bis (11 December 1854); ANS 13G23.3.

36. Alfa Umar Thierno Bayla Wan, as he is usually called, had been recruited by Umar in 1846-7. ANS 13G120.20,25 and 27; Tyam, Qaçida, p. 49.

37. Carrère and Holle, Sénégambie, pp. 201-2. See also ANS 13G166.85; Soh, Chroniques, p. 77; Tyam, Qaçida, pp. 43-52.

38. ANS 2B31bis (12 and 26 December 1854); ANS 13G166.79, 83 and 84; Carrère and Holle, Sénégambie, pp. 201-4; Mage, Voyage, pp. 148-9.

39. Carrère and Holle, Sénégambie, pp. 205-6. The Arabie original is found in ANF, OM SEN.1.41b (Faidherbe to the Ministry, 11 March 1855). This letter was widely quoted to portray Umar as hostile to the French. Cf. Annales, p. 112 ; Hargreaves, Prelude, p. 102.

40. ANF, OM SEN.4.44a (copy of letter of 3 October 1855, Faidherbe to the Commandants of the Upper Senegal) and 44e (extract from the minutes of the Conseil d'Administration of St. Louis, 20 August 1855).

41. To designate the Bundu dynasty, I have chosen the singular form of the patronym, Sy, rather than the plural, Sisibe. For the struggles in Bundu, a fragmentary account can be pieced together through the Bakel archives, beginning with items for June 1852 (ANS 13G166-7). A fuller perspective can be found in Carrere and Holle, Sénégambie, pp. 162 ff. ; Kamara, Zuhuur, I, ff. 155-7 ; Rançon, “Le Boundou”, pp. 517 ff.

42. ANS 13G167 (letters of I July and 10 October 1855), 18 and 22 February 1856). These references came in a personal communication from Philip Curtin. See also Annales, p. 117.

43. F. Carrère, “Siège de Médine”, Revue Coloniale, 19 (1857), p. 54. Umar is often pictured as attacking Medine reluctantly, at the insistence of his followers (Delafosse, “Traditions”, p. 362; “Diallo manuscript”, p. 17; Sissoko, “Chroniques”, 1937, p. 18; Tyam, Qaçida, p. 101), but it is none the less true that he needed to reassert his control in the Upper Senegal. People in Futa were well aware of the struggle, and reinforcements arrived to support the siege in July. Tyam, Qaçida, p.103.

44. For the damage done to the Umarian forces, see Mage, Voyage, pp. 156-7; Sissoko, “Chroniques”, 1937, pp. 18 ff. Mamadu Hamat was apparently killed (ANS 2B32 of 10 August 1857; Kamara, Zuhuur, II, f. 191 ; Tyam, Qaçida, p. 102 n.), although there are also reports that someone of the same name and nickname died in 1875 (FR, Birane Top ; Kamara, Zuhuur, II, ff. 184-5 ; Soh, Chroniques, p. 89).

45. ANS 13G9.5.36 (memorandum of 23 October 1855).

46. ANS 3B77.Podor.l2 (15 December 1856); ANS 13G120.61. The name of the kinsman of Umar is not given.

47. ANS 13G140.5 (received by Faidherbe 20 August 1857, and printed in the Moniteur of 1 September 1857). A few months later the Commandant of Podor gave Mamadu Biran 10 guinées, an indication that there may have been some material inducement involved in the Wan leader's change of position. ANS 13G120.96.

48. For the Matam events, see ANS 3B96 (5 July 1857); ANS 1D9 (report on events of 13 September 1857); ANS 13G140.5,25; Moniteur, 8 and 29 September, 13 October, 22 December 1857, and 2 February 1858.

49. For Garii, see FR, Amadou Wendou Node Ndiaye, session 2; FR, Sega Niang, session 1 ; Annales, p. 164.

50. For the French directives on Umar and the Lower Senegal, see ANS 13G23.6 (2 September 1858). For the emphasis on Kenieba gold, see Duval, “Politique”, p. 861, where he indicates that the French were obtaining only one-seventh to one-eighth of the annual colonial budget of Senegal from local sources. See also Annales, pp. 162-3.

51. For the Dimar protectorate, see ANS 13G9.4. The reports of the observation posts are found in ANS 1D13, passim.

52. For Umar's visit to Futa in 1858-9,1 draw from an interview with Mountaga Tal, Dakar, 22 February 1968; Mage, Voyage, pp. 158 ff.; Moniteur, beginning with 20 April 1858 ; Sissoko, “Chroniques”, 1937, pp. 127 ff. ; Soh, Chroniques, pp. 77 ff. ; Tyam, Qaçida, pp. 111 ff. For an account of a “trial” of the “sins” of Futa, presumably conducted by Umar in the fall of 1858, see FR, Al-Hadji Ismaila Sam, session 4 (passages of Hamady Sayande Ndiaye).

53. Tyam, Qaçida, pp. 113-14.

54. Kamara, Zuhuur, II, f. 11. For the opposition to Umar, see also ANS 13G-157.39; ANS 13G167.72; Moniteur, 7 and 14 September, 1858.

55. ANS 2B32 (15 January 1859); ANS 13G120.112; ANS 13G140.22; ANS 13G167.76,84,99.

56. ANS 13G118 (9 October 1858, letter from #145;Eliman Nehdi” or the Madiyu); ANS 13G140.14, 17-20, 22-4; ANS 13G136.26; ANS 13G157.42. For the Wan slaves, see ANS 13G140.40 (August 1860); ANS 13G169.14 (19 April 1864).

57. For Toro, in addition to page 46, note 2, see ANS 2B32 (15 January 1859); ANS 13G120.113-15; ANS 13G140.21. Umar apparently forced Mamadu Biran to accompany him to Toro. Moniteur, 11 and 29 January 1859; interview with Mountaga Tal, 22 February 1968.

58. ANS 3B96 (15 February 1859); ANS 13G23.7; ANS 13G120.116-18; Moniteur, S and 15 February, 1 -3 March 1859.

59. For Mamadu Mamudu Kan, a cousin of Abdul Bokar, see Kamara, Zuhuur, II, f. 30; for Sada Kan of Mbolo Biran, see an interview with Thierno Seydou Kane, 26 April 1968; FR, Cheikh Bandel Wane; Mage, Voyage, p. 456. On Hamat Sal, see the interview with Mountaga Tal cited in note 51 ; Tyam, Qacida p. 177. For Bokar Sammolde Ba, the cleric from Hore-Fonde, see FR, Al-Hadji Bokar Ba; FR, Thierno Amadou Bokar Alfa Ba, session 1 ; FR, Mamadou Dia, session 2. For several tax-collectors from the central and eastern provinces, see Kamara, Zuhuur, II, f. 102.

60. The 40,000 figure comes from Mage, Voyage, p. 160. For other material on the size of the migration, see ANF, OM SEN.1.46a (13 April 1860); ANS 13G-120.122; Moniteur, 3 August 1858.

61. ANS 13G140.31 (no date, about July 1860, Faidherbe to Futa).

62. For the effects of the emigration, see ANS 13G140.51 ; ANS 13G147.17; and the catalogue of villages in the Fonds Gaden, Cahier 3 (IFAN, Dakar). Kamara writes that there were even some examples of cannibalism, so great was the distress of the people (Zuhuur, II, f. 342). The commander of the Sedhiu post in Casamance reported that over 2,000 refugees from the “ravages of al-hajji in the upper country” had come into his area by July of 1859. ANS 13G264.21.

63. Laam Julɓe is the Pular equivalent of the Arabic, amiir al-mu'miniin or “Commander of the Faithful”. The 1860 “understanding” was never signed but it is an accurate description of relationships for the following period. See Saint-Martin, Relations, pp. 91-110; A. S. Kanya-Forstner, The Conquest of the Western Sudan (Cambridge, 1969) (hereafter Conquest), p. 42.

64. Saint-Martin, Empire, p. 90; Willis, “Jihaad”, p. 405 n. For the use of hijra to designate any movement of withdrawal and consolidation by a Muslim reformer, see Last, Sokoto, pp. 23-9. For the influence of the “Umarian hajjis” upon returning to Senegal, see P. Marty, Etudes sur I'Islam au Sénégal (Paris, 1917) (hereafter Sénégal), I, pp. 91 ff.

65. The return of many of the Umarian migrants to Futa with tooroɓɓe status helps to explain the large percentage of torodBe in the present-day population of the Tokolor. See page 26, note 1; Boutillier, Moyenne Vallée, pp. 20, 54.

66. For the standard protectorate treaties, see the appendices to Annales, pp. 395 ff. ; J. Duval, Les Colonies et la politique coloniale de la Frame (Paris, 1864) (hereafter Colonies), pp. 66-9. For expressions of the strategy of seeking out lineages hostile to the tooroɓɓe regime, see C. Faure, “Le premier séjour de Duranton au Sénégal,” Revue de l'Histoire des Colonies Françaises, 1921, pp. 251-3 (for the views of Duranton); Raffenel, Nouveau voyage, I, pp. 496-9, and II, pp. 55-7, 250 ff.

67. ANS 13G5, p. 75; Moniteur, 19 April 1859. Umar appointed three chiefs in Toro during his stay there in 1859: one for the Seloɓe tooroɓɓe, one for the Wodabe Fulɓe and one for the Ururɓe Fulɓe. He was much closer than the French to the traditional pattern of rule. ANS 13G120.113.

68. ANS 13G157.52, 54; ANS 13G168.31 ; Moniteur, 20 September 1859.

69. For the Salde agreement, see ANS 13G5, pp. 101-2; ANS 13G147.6. For the treaty with Almamy Mustafa, see ANS 13G5, pp. 99-101 ; Moniteur, 2 and 30 August 1859. In July 1859 Faidherbe also circulated a long Arabic statement criticizing the claims and actions of Umar. For the Arabic text and French translation, see Moniteur, 12 July 1859.

70. ANS 3B96 (letter of 11 September 1857). See also ANS 130140.39,48; Moniteur, 30 August 1859; Soh, Chroniques, p. 80.

71. Holle had served the St. Louis administration since the 1820s and commanded key posts in times of crises (Medine in 1857, Matam in 1858-9, Salde in 1860). For a summary of his life and contribution, see E. Saulnier, Une Compagnie à privilège au XIXe siècle : la compagnie de Galam au Sénégal (Paris, 1921), p. 136.

72. ANS 130250.6,8-9.