Clarendon Press. Oxford. 1975. 239 pages

Futa Toro in 1860 was only the shadow of its former self. Twenty per cent of its people had left, including virtually a whole generation of eligible and electoral leaders. The agricultural cycle did not recover for several years from the turmoil occasioned by the confrontation of Umar and Faidherbe. Ostensibly, the French had won that confrontation, in terms of land if not people, and their victory was symbolized in the new forts at Podor, Salde, and Matam. The true test for St. Louis, however, was the fate and fortunes of its key allies in Western, Central, and Eastern Futa. They faced the Herculean tasks of restoring some measure of order and prosperity, and justifying their right to rule in the name of the French.

Elfeki Mamadu Any was trying to rule Eastern Futa without any significant traditional claim to the allegiance of the people 1. To buttress his position, the French sent gunboats to protect the two river villages controlled by his family and instructed the Commandant of Matam to provide additional support. Elfeki Mamadu used their aid to impose new taxes and to raid villages with an army of former slaves picked up in the wake of the Umarian exodus. These acts thoroughly eroded the authority of the Any and the French in the region by 1862.

In Western Futa the administration candidate was doing little better. The first Lam Toro, chosen for his opposition to Umar rather than for any other qualities, was revoked after a year in office. His replacement was equally ineffective, and the residents of Toro complained constantly to the Podor Commandant about new exactions. The grievances were particularly acute in eastern Toro and the village clusters of Havre and Halaybe, where the Lam Toro had little or no traditional authority 2.

Almamy Mamadu was in a somewhat better position in Central Futa. The Wan had established their influence well before Faidherbe and Mamadu Biran was now serving his tenth term as head of state 3. He strengthened his network of alliances still further, including a marriage link to the chiefly family in the village next to the Salde fort, and enjoyed good relations with the commandant there, Paul Holle.

In the spring of 1860 Mamadu began to assert his conception of the Almamyship 4. Supported by Holle and a gunboat, he ventured into Bossea province, collected taxes and fines, and replaced an important village headman with his own candidate. While there, he met Elfeki Mamadu, and made explicit what he had already agreed to in private, that Eastern Futa no longer fell under the authority of the Almamy and the electors of Central Futa. It was a paradoxical performance: while claiming unprecedented authority over the influential inhabitants of Bossea, he had renounced his traditional jurisdiction over a whole region. Bossea wasted little time in making its grievances known and began to campaign for the candidacy of Mustafa, the ex-Almamy.

By the summer Mamadu Biran was on the defensive. In June he permitted Bossea and the other Futanke provinces to mobilize a retaliatory column against pillages from neighbouring Jolof 5. In one of the ensuing skirmishes his brother was killed and Mamadu thereby lost his best general and probably his most articulate advocate with members of the electoral council. In September a French lieutenant took advantage of the flood stage to sail up one of the Senegal tributaries and map the jeeri of Eastern Futa and Bossea 6. He was threatened and jostled in Hore-Fonde, and the Almamy was soon caught in the crossfire between those who blamed him for allowing the French to travel in Futa and the Governor's insistence upon apologies and reparations. When he failed to resolve this issue and to restore the “dismembered” wings of Futa, he was replaced by his own half-brother, Amadu Biran, in April of 1861 7.

The electors had chosen the best possible way to express their dissatisfaction with the Wan patriarch. Amadu Biran would now rule from Mbumba and take over the vast fields, slaves, and retainers formerly controlled by his brother. No love was lost between the two men. Their mothers had been bitter rivals for the affection of the father, and transmitted their enmity to the next generation. Mamadu mobilized his supporters and delayed Amadu's installation in Mbumba for two months, but he finally retreated to the home of his maternal relatives.

In August, Mamadu's son Ibra slipped quietly into the family fields, met his uncle Amadu and shot him on the spot 8. The Almamy died after a few days and Futa was thrown into turmoil. Chiefs of state had been assassinated in the past, but never openly by members of their own families. Mamadu, Ibra, and their followers acknowledged the shock and criticism of the Futankoobe and, like Adam and Eve driven from the Garden of Eden, retired to Western Futa where they could count on friendly relatives and French support. After Mamadu refused to bring his son to trial, the electors chose another Almamy from Law province 9.

It was into this situation of decline and confusion that a young man of thirty stepped to make his bid for power. He was Abdul Bokar Kan, grandson of the famous Ali Dundu and now a jaggorgal in his own right. Consistent with this electoral heritage, he pursued neither the way of Umar, who used his Meccan and Tijaniyya credentials to proclaim a new order and a reforming mission, nor the path of the Wan, who had converted their original credentials of Islamic learning into wealth and alliances in hopes of gaining a permanent title to the Almamyship. Abdul was a young war-lord, creating a reputation for adventure and generous distribution of spoils, an ideal base from which to approach the chaos of Futa in the early 1860s 10.

On the threshold of his career, Abdul's strong suits consisted of his Bossea provincial identity, his Kan lineage identity and his own personal qualities. Bossea was the most densely populated area of Futa, and exercised a disproportionate influence in the rest of the country through its three seats on the council jaggorɗe. Although one elector might dominate a decade or period, no single lineage was pre-eminent in the area and this tended to increase Bossea cohesion, especially in cases of external threat. Adding to the cohesion was the relative fluidity of class lines in the province, reflected in intermarriage among free and noble groups and access to tooroɓɓe status for families of Fulɓe and seɓɓe origin. In the somewhat exaggerated opinion of one commentator,

The BosseyaaBe [inhabitants of Bossea ; sing. Bosseyaajo] are very generous people with their material possessions. They are the most intelligent, wealthy, shrewd, and brave. They are the quickest to refuse compliance and to provide protection. Because of this they ruled Futa, and no one ever reigned without their support. If they sought by stratagem or fighting to remove the ruler, he was removed 11.

Throughout his adult life, Abdul used his Bosseyaajo identity to best advantage. Ali Dundu established the reputation of the lineage by discarding the pastoral vocation of his Fulɓe ancestors to become a minister of Almamy Abdul in the new tooroɓɓe regime. In the process he changed his clan name from the Fulɓe form of Diallo to its Tokolor equivalent of Kan. In the machinations surrounding the first Almamy's demise, he emerged as the pre-eminent elector in the new council and remained the most influential single figure in the country until his death in 1819 12. In the next two decades, Falil Atch of Rindiaw dominated Bossea and Futa politics and even forced his Kan rivals to leave their north bank village to settle on the southern side at Dabiya Odedji. It was there that Ali's son Bokar and his wife Jeynaba gave birth to Abdul about 1831 13.

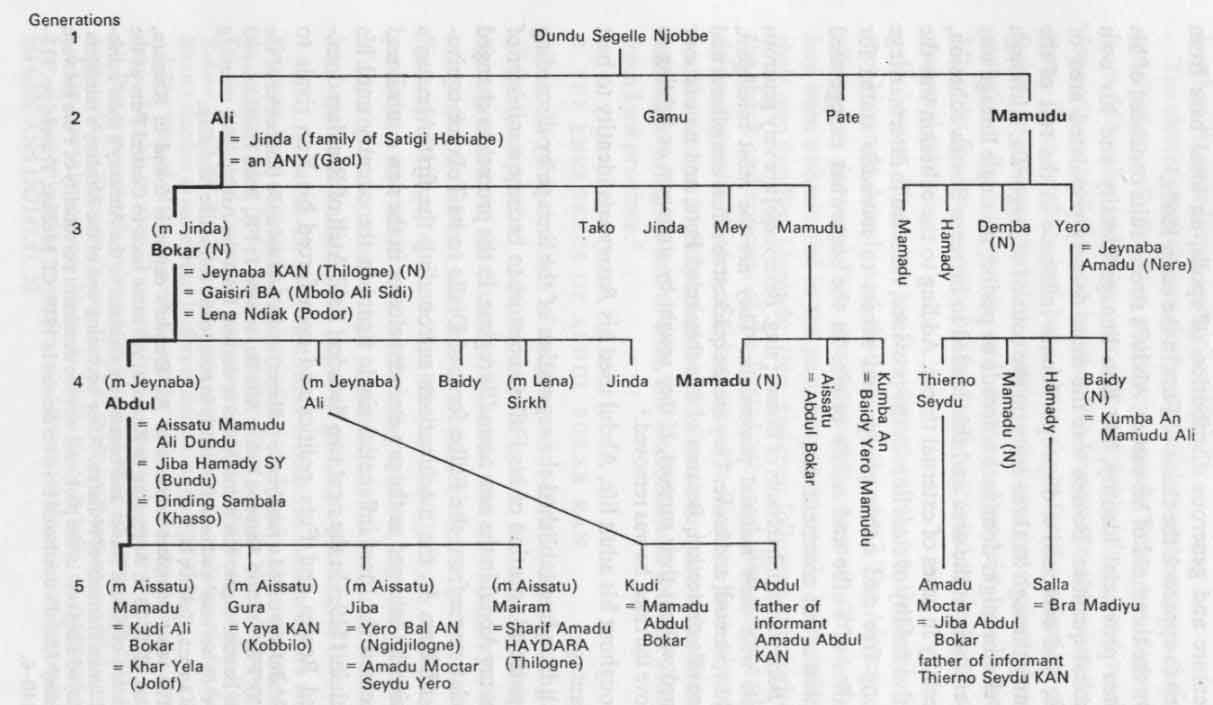

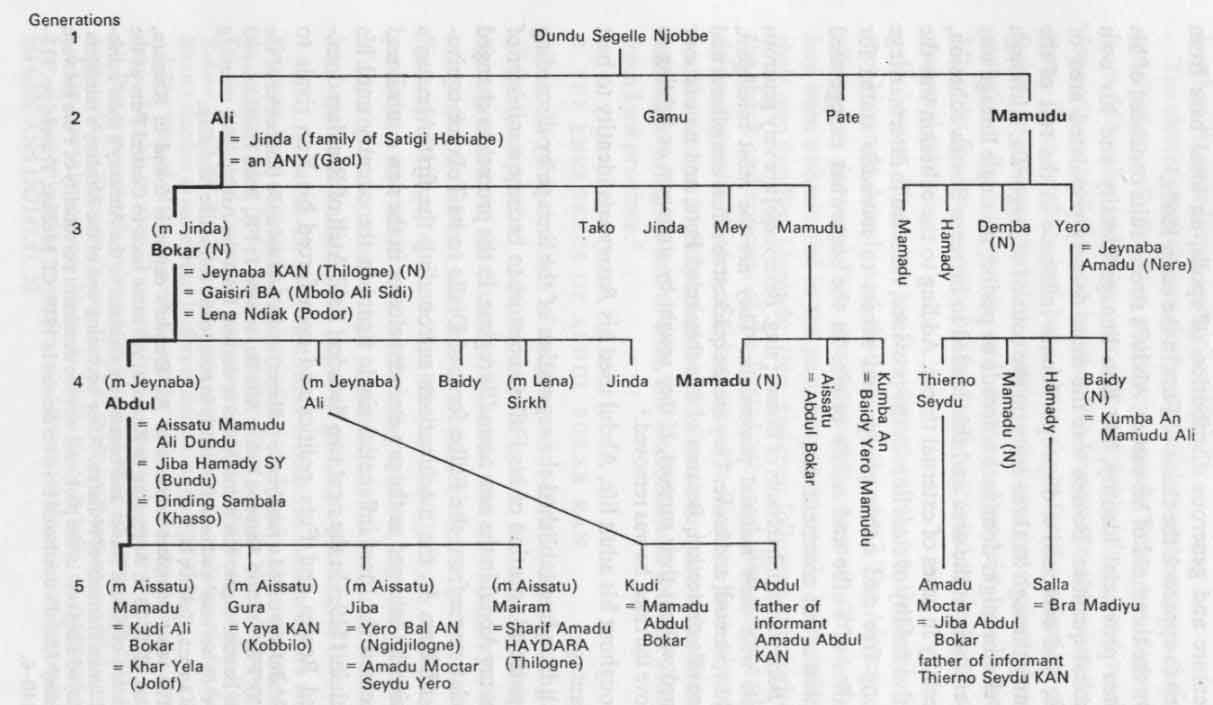

Genealogy of the Kan Family of Dabiya (partial list)

In the 1840s Bokar Ali Dundu began to raise the fortunes of the family 14. He signed the official letters of Futa right after the Almamy and Falil, and was such a frequent visitor to the Wan court in Mbumba that a part of the village square was designated “the place of Bokar”. He reasserted Kan control of tax fiefs in Western Futa and helped consolidate his influence by marrying the daughter of a wealthy Podor merchant. The French recognized this influence when they secretly sought and secured his acquiescence in the scheme to build the fort in 1854 15.

Bokar never showed great enthusiasm for the Umarian mission but, like many Futankoobe, found himself participating just the same. There was cause for enmity between the Kan and the Tal, since Ali Dundu had received tax rights over Halwar, Umar's birth-place. Some traditions register an attempt by Bokar to seize the Tal fortunes or kill Umar during his visit to Futa in 1846-7 16. The Kan elector none the less joined in the 1854 procession to Farbanna, stayed with the Sheku and fought in the campaigns until he died in the early 1860s. In 1859 he was joined in the east by his wife and cousin, and the mantle of leadership in the family passed to his oldest son, Abdul.

Abdul's decision to resist emigration and stay at home was characteristic of the independent judgements which marked his career. He perceived quickly that his role in any reform movement would be subordinate and that his most promising future lay in Futa in the kind of network of alliances fashioned by his grandfather and father. He received the usual Koranic education and learned enough Arabic to read and write rudimentary letters. Basically, however, he was raised in the jaggorgal tradition and learned the art of politics and war from Bokar. The oral traditions about his adolescence emphasize two qualities: a strong desire to exercise power, and a disdain for accumulating wealth. When he was about twenty, at precisely the time earmarked by Futanke custom for “sowing wild oats” with the fedde or age-grade of one's peers, Abdul acquired the reputation of a brilliant pillager who gave away all he took, a kind of Robin Hood of the young 17.

The logical next step for his military and political apprenticeship was the Umarian movement, despite the traditional hostility between the Kan and the Tal. Like many of his contemporaries, the Bosseyaajo took his following to the Upper Senegal in the 1850s and supported the reformist cause in the succession struggles in Bundu. Just as they were on the point of victory in one battle, the French sent reinforcements to their opponents. Abdul, as prudent as he was daring, persuaded the Umarian army to withdraw. The Sheku had harsh words for this retreat under fire but had no way to discipline the young leader, who soon tired of jihaad and returned to Futa 18.

In 1858 Umar sent gifts of slaves to Abdul and his cousin, apparently to hold them to earlier promises to migrate to the east. While the cousin met Umar in Bossea and fulfilled the obligation to depart, Abdul avoided contact, sold the slaves for cattle, guns, and cloth, and distributed the lot to his followers 19. When the Sheku left Hore-Fonde for Western Futa, the young Bossea leader helped elect Mustafa Almamy as a way of mobilizing resistance. When the Umarian procession swept back through Central Futa in March and April, Abdul let them go by and then moved in behind the caravan to perform the most daring deed of all. According to one well-known oral historian of Bossea, Abdul pursued Umar as far as Dembankane [the last town in Futa before crossing into Gadiaga and the Upper Senegal] and stole, bit by bit, the cleric's cattle. Umar prevented his warriors from intervening, telling them:

«You don't understand the secret hidden in Abdul. Between his head and his waist is lodged the quality of a saint. Between his waist and feet is the impulse to pillage. I won't take him with me. His true character will appear one day.» 20

The Bosseyaajo did not make the same distinction between saintliness and banditry. To him, harassing the Umarian procession and slowing migration were a vital part of defending Futa Toro against its enemies, who might come in the guise of Islamic reform as well as in the form of European gunboats. He was particularly incensed that his mother had been forced to depart, and spent the autumn of 1859 trying to mobilize a counter expedition to bring back those who had left against their will. En route to see Almamy Bokar Sada of Bundu, he declared to the Bakel Commandant;

All Futa will rise up together with all those from Galam [Gadiaga] and Gidimakha who wish to join us. Bokar Sada is one of us. By going to Medine we will get the support of Sambala. With all this [participation] we are sure to succeed. Our goal will be to protect the return of those innumerable people who wish to come back home 21.

The particular plan came to nought, but it did mark the beginning of Abdul's lifelong opposition to the Fergo Umar. On the side, he contracted a marriage with Jiba, Bokar's niece. This tie became an important part of his network of alliances 22.

In the aftermath of the Umarian exodus and the chaos it left behind, Abdul was admirably placed to enter the game of Futanke politics. Almost an entire generation of leaders had gone east in the 1850s. Their successors were less influential and in some cases compromised by their flight from Umar or their acceptance of French expansion. In contrast, he was too young to be blamed for the errors of the past, had no history of association with the Europeans, and almost alone among the Futankoobe had dared openly, albeit judiciously, oppose the migration of 1858-9.

Abdul made his first move for power in 1861 in Eastern Futa, where the excesses of the Elfeki and the French provided much of the needed ammunition. His initial base consisted of tax fiefs in the jeeri going back to the days of Ali Dundu 23. His first allies were a group of Brakna Moors called the Awlad Ely, some of whom had participated in his age-grade of pillagers. Then the young elector established the link which allowed him to dominate the eastern region during much of his career: the alliance with Malik Hamat Dia, the leader of the Kolyabe warriors of the river village of Ngidjilogne 24. The Kolyabe had furnished the main fighting force of the Satigis before dispersing into several villages of Eastern Futa in the late eighteenth century. Malik controlled several of these villages and, by choosing to work with Abdul Bokar, he condemned to failure the effort of Elfeki Mamadu and the French to rule the region.

By 1862 Abdul and Malik had established their hegemony over the jeeri and much of the waalo 25. In these areas they collected payments in grain and animals in exchange for protection, expropriated vacant fields for their followers and confirmed the village chiefs in office. At times they exacted contributions from the traitants working out of Matam. Elfeki Mamadu was forced out of Gaol, his residence near the Bossea border, and retreated to his second village at the far end of Eastern Futa. His son Baidy began to collaborate with Abdul and St. Louis withdrew its gunboats, thereby acknowledging the failure of their policy in the region.

In the eight months between July 1862 and February 1863, the French and Futanke armies engaged each other in two pitched battles and in a running series of skirmishes, all this in striking contrast to a general record of avoiding confrontation. The answer to the riddle lies in the reassertion of sovereignty by the Almamate and, even more, in an aggressive effort to imitate Faidherbe's forceful policy by a new and inexperienced governor.

Jean Jauréguiberry took over the reins in St. Louis in December 1861, and soon alienated the team of advisers and commanders who had worked so closely with his predecessor 26. He had weaker ties than Faidherbe with the trading community, who tended to restrain French expansion in areas that were commercially important. By contrast, he paid close attention to some of the mulatto and black officials of the administration who sought to enlarge French holdings and thereby enhance their own influence.

Jauréguiberry launched his forceful policy early in 1862 in an effort to restore the now discredited treaties and chiefs established in 1859 27. French gunboats and garrisons patrolled the river to protect traders and letter-carriers while an expedition in Western Futa imposed taxes on jeeri villages and deported a Futanke leader to the coast.

In response, Abdul Bokar and the other Futanke chiefs stepped up their campaigns of reprisal, effectively stopped all trading activity and drove the allies of the French into the shelter of the forts. Where they had previously been hostile to the Umarian mission, when it meant emigration to “Nioro”, they now based their case on the reformer's message about the sovereignty of Futa. Encouraged by the Sheku's victory in Masina, they inaugurated as Almamy an Umarian partisan named Amadu Thierno Demba Ly. Almamy Amadu promptly claimed control over Eastern and Western Futa and insisted that his country had never agreed to the “dismemberment” imposed in 1859. Fresh from his installation in early July, he wrote in bold terms to the Governor:

[This letter] is an indication to you that all of the people of Futa have sworn allegiance to me and agreed that I should succeed to the position of Almamy, given the fact that the Walii [Saint] of Allah, Al-Hajj Umar, designated me. They regret their past rebellion against [the recommendation of] the Walii and have entrusted their affairs to this Almamy. If you desire that peace and tranquillity reign between Saint Louis and Futa, send your representatives to the Almamy… 28

The issue was thus joined in the old categories articulated by Umar and Faidherbe, even though neither protagonist was on the scene. Jauréguiberry decided to force compliance and, in the last days of July 1862, debarked about a thousand European and Senegalese soldiers at Dirmbodya, site of the old customs payments to the Alcaty. With their artillery and superior small arms fire, the French quickly routed the forces of the Almamy and burned Hore-Fonde and several other important villages of Central Futa. They lost four men, compared to over sixty Futankoobe. The colonial forces then retired to their boats and re-embarked for St. Louis, fearing the heat, humidity, and contagion of the rainy season 29. While they chalked up the affair as a clear victory, their opponents saw it as a draw because the French had quickly pulled back to the river, apparent proof that they could not really stand fighting on land 30. Such conflicting interpretations of battles were common in French-Futanke relations in the late nineteenth century. They arose from different perspectives and the need of each side to justify its actions.

During August the attacks on trade continued unabated, threatening the commercial campaign of 1862-3. The French called on Mamadu Biran to mediate, and even persuaded Bokar Sada to come from Bundu to urge Futa to negotiate 31. It was to no avail, and in mid-September the new Almamy and Abdul Bokar entered Western Futa to answer the long-standing challenges of Podor and the protectorates of Toro and Dimar. As with Umar's march in 1859, the local response was enthusiastic and the emboldened army moved downstream to Bokol, a town near the fort of Dagana. This time the Governor's response was devastating. 900 men left their boats, crossed to the jeeri and routed the Futankoobe in the scrub bush and termite hills beyond the village. Then, using the tributaries of the river swollen by the flood, the French boats pursued the survivors back to the east and deported the village headmen who had provided support 32.

There was no way for the Almamy to pass Bokol off as a victory or draw, but Futanke hostility persisted through the fall of 1862. Part of the Matam garrison was nearly annihilated in an ambush, and a convoy was attacked on the river. Almamy Amadu appointed Samba Umahani Sal as Lam Toro in a direct slap at the French appointee. The ambitious and able Samba went to Toro, undermined his cousin's authority and even captured the provincial capital of Gede for a few days 33.

Jauréguiberry saw these acts as part of a much larger plan. His principal source of information was Aliun Sal, a young Senegalese lieutenant who returned in October 1862 from a long exploratory mission in the area of Timbuktu and Masina. Identified as a “Saint Louisian” and potential spy, Aliun had spent some days as a prisoner of an Umarian contingent and was now spreading an amazing account of the Sheku's intentions. A later paraphrase of the story declared that Umar, master of all the Upper Niger through his last victory [over Masina in May 1862], was now able to turn his attention to his plan of vengeance against the French who had chased him from their possessions. To this end he sent emissaries to all the Moorish chiefs to request their support. Two columns were to co-ordinate their efforts, one on the right bank of the Senegal River commanded by Al-Hajji himself, the other on the left bank under Alfa Umar [Wan]. They were to descend from the upper river, destroying everything in their way, and arrive finally in St. Louis to expel the Europeans once and for all 34.

Rumours circulated that the Senegambians saw the Umarian drive to the sea as the end of the “prophesied seven year reign of the whites”, corresponding roughly to the term of Faidherbe and the period of French expansion along the river. The Governor used these reports to paint a picture of the whole interior rising in arms and requested reinforcements from Paris. He ended his letter of October 26 by writing, “Our prestige is in the balance, we must not hesitate.” 35. It was not the last time that French officials on the spot would exaggerate or invent crises for the benefit of the Ministry.

By January 1863 Jauréguiberry had received the additional troops and mustered a force of about 1600 European and Senegalese soldiers, supported by an elaborate convoy of gunboats and supply barges 36. Beginning at Podor in mid-January, the column swept through the jeeri of Western Futa and then on as far as Matam before returning to St. Louis at the end of February. During six weeks it won three battles, fought sixteen skirmishes and destroyed seventy-six villages. In the process, the French lost twenty men in combat and at least twenty-nine more by disease, extremely high figures for a colonial campaign. Criticism mounted against the Governor and Paris decided to end his term 37.

The Futankoobe called the expedition the duppal borom or “burning by the governor” 38. Their losses far exceeded those of the French, but it was none the less possible for them to find some solace in the final results. The column had, after all, withdrawn and left no additional garrisons to consolidate its victories. Abdul Bokar attacked the flanks of the army in Bossea, just as he had done with Umar in 1859, and this inconclusive skirmish was translated into a Futanke triumph and the cause of the withdrawal 39. Most of all, Abdul, Almamy Amadu, and Samba Umahani returned to Western Futa in February, re-established their sway over much of the region and assassinated the French-appointed Lam Toro. In late March Jauréguiberry, already notified of his recall, even recognized Samba as the new chief of Toro 40.

Jauréguiberry's replacement was none other than Louis Faidherbe. Now a general, Faidherbe brought back the core of officers who had served with him before and took charge in July 1863 41. Although much less inclined to expand along the river in his second term, he was sharply critical of his predecessor's “capitulation” in Toro as well as his expensive campaigns. He had the Podor Commandant issue an ultimatum to Lam Toro Samba to board a gunboat and swear allegiance to the colonial regime. Samba refused and this gave the French the excuse to install a more pliable successor named Muley. Samba then withdrew to Central Futa and the protection offered by Abdul Bokar 42.

Faidherbe also took the occasion to get back in touch with Mamadu Biran, who had been allowed to return to Mbumba some time after the assassination of his brother. Abdul and the other chiefs were weary of the year of battles under their Umarian Almamy. In July they decided to cast their lot with the aged but crafty Wan leader, who carefully advertised his ability to reconcile French and Futanke interests. In August a French envoy came to Mbumba to sign a treaty reaffirming the agreements of 1859 and rejecting, for the first time in writing, the Almamy's sovereignty over Western and Eastern Futa. Conspicuous by the absence of their signatures, however, were Abdul and representatives of three of the other four principal electoral

families 43.

Mamadu Biran reigned without major incident until the spring of 1864, when tension began to rise sharply in every quarter. Recruiters from “Nioro” urged emigration because the Almamy was beholden to the French and traitants were attacked on the river. In April Samba Umahani returned to Western Futa to threaten the control of Muley, while the French candidate for the Brakna Emirate had to flee from a hostile Moorish coalition 44.

These events had their counterpart in the deterioration of the relationship of Abdul Bokar and the Almamy. The Bosseyaajo, in an effort to improve his Islamic credentials and strengthen alliances, sought the hand of one of Mamadu's daughters. Where other suitors had been successful, Abdul was refused in very abusive fashion when the Wan leader said :

« From Dundu [forest, in Pular, but also the name of Abdul's great grandfather] nothing has emerged save the black man [with the connotation of primitive and pagan] and the snakes.»

Abdul received the message and replied :

« Then the black man from the forest will crush him [Mamadu] and the snakes of the forest will bite him ! » 45

Stung by these allusions to his recent Fulɓe origins, Abdul confiscated the property of a wealthy estate that normally would have gone to the Almamy. Mamadu, incensed by this challenge to his authority and eager to vent his hostility towards Bossea, decided to invade and co-ordinated his efforts with Faidherbe.

In July 1864 a French convoy sailed up to Bossea, bombarded the villages responsible for the attacks on traitants and occupied Kaedi, an important market and a base for Abdul and the Awlad Ely. At Kaedi the troops destroyed 2,000 Tokolor homes and 200 Moorish tents and announced plans for a new fort 46. Reinforced by the convoy, Mamadu Biran led his forces into the Bossea highlands, deposed the Thierno Molle for “collaboration” with Abdul and drove the Kan elector into the Ferlo with only a handful of followers 47. At the same time the Commandant of Matam proclaimed a new regime in Eastern Futa. After capturing and deporting Elfeki Mamadu and his son, the commandant appointed the son of Almamy Abdul Kader as the new chief of the region, hoping that his prestige would undermine the influence of Abdul 48.

Like most frontal attacks on Futa, this one failed to establish a pro-French regime. In part, this was because one phase of the original offensive, construction of the Kaedi fort in the heart of Bossea, was never implemented. For the first time Paris vetoed Faidherbe's plans for expansion along the Senegal by refusing to allocate funds, marking the end of major French initiatives along the river until the late 1870s 49. Equally important was Abdul Bokar's ability to pin the label of “French” on Mamadu Biran and portray himself as the defender of the homeland. He moved into the Ferlo in a tactical retreat reminiscent of deposed Satigis and Almamies seeking to return to power 50. In the wilderness setting he quickly attracted followers and made his usual promises of generous distribution of booty. Then he confiscated the gold and grain stores of a wealthy village, passed through Eastern Fula and effectively removed the new French appointee, and returned to Bossea to prepare the downfall of Almamy Mamadu. In October he managed to depose the Wan leader and put Amadu Thierno Demba back at the helm 51. In November, Faidherbe's representative came to Dirmbodya to negotiate, thereby recognizing that the offensive of July had achieved nothing.

The resulting agreements set a pattern for French-Futanke treaties in the late nineteenth century. On the one hand, the new Almamy and most of the chiefs signed a virtual copy of the 1863 accord, thereby renouncing all authority over Eastern and Western Futa. The single exception was Abdul Bokar, who typically refused to attend. The Almamy saw the treaty as a temporary measure to achieve peace, rather than a recognition of the “dismemberment” of Futa. On the other hand, the French envoy met Abdul's agent and gave him secret assurances that St. Louis would not challenge Abdul's effective control of Eastern Futa. Faidherbe printed the public treaty in the local paper and sent a copy to Paris for its consumption, keeping the private assurances to himself 52.

In December 1864 and January 1865 Abdul completed his revenge on Mamadu Biran. Joining with the Awlad Ely, he sacked Mbumba twice and drove the Wan leader back into exile in Toro. He took many slaves and cattle and exploded the myth of the impregnability of the Law capital. In the ensuing period Abdul made a point of touring the villages of the province to collect the taxes that customarily went to Mbumba. The ageing Mamadu returned to his capital after a few months, and died in 1866 53.

Abdul Bokar, now in his early thirties, had proved himself particularly adept at playing the game of politics and war in Futa. As one Commandant of Bakel said, “His explanations are frank, and this tribal chief understands perfectly his interests, and even [expresses them] with a rare impudence” 54. His core following consisted primarily of young Fulɓe, seɓɓe and Moors with little attachment to the traditions of the Almamate or the position of particular tooroɓɓe families. They were free to oppose the Umarian mission when it meant migration to a distant land and to use it to bolster their cause when threatened by French attack. Abdul had carefully avoided signing any agreements or even being seen with Europeans, and could in no way be blamed for whatever diminution of size and power had occurred in Futa since 1854. Although he had not institutionalized his position in the fluid politics of Futa, he had become the dominant voice on the electoral council, and earned the reputation of chief defender of the homeland.

Notes

1. ANS 1D13.38-39; ANS 13G157.52, 57, 65, 74-5; ANS 13G167.94; ANS 13G168.1, 17, 22. In the wake of the Umarian migration many former slaves escaped or were left behind. Some of them were mobilized into a raiding band by a seɓɓe leader named Jubayru Bolo of Horkadiere and preyed on the trading caravans, grain stores, and herds of Eastern Futa. When Jubayru was captured and deported by the French in the summer of 1860, most of the slaves were taken over by Bubu Sire Any, brother of Elfeki Mamadu, Bubu then began to raid in the same fashion. The effect was to make life in Eastern Fina more precarious than usual. Kamara, Zuhuur, I, ff. 220, 342-3.

2. ANS 3B96 (6 and 13 January 1860); ANS 13G136.38-9. The new Lam Toro was Sire Geladio (1860-3). ANS 13G137, p. 194.

3. The term is based on Robinson et al., “Chronology”, pp. 574-6. For the marriages arranged by Mamadu Biran, see Kamara, Zuhuur, II, ff. 41,183 ff. For the electors in the early 1860s, there is little information. Amadu Samba Dundu Sal of the Bossea riverfront was somewhat prominent. ANS 13G140.60a, 72.

4. AN 13G140.39.,48,51.

5. ANS 13G120.131 ; ANS 13G140.49; Kamara, Zuhuur, II f. 187.

6. ANS 13G140.52;ANS13G147.18-20.

7. ANS 13G147.28-29, 36-7, 40-3; ANS 13G208.156. Amadu Biran's mother, Fatumata Baro, supposedly beat her frailer rival, Tako Ly, the mother of Mamadu, to compensate for her inferior prestige. The Ly family blamed Fatumata for Tako's death and demanded compensation from the Baro family. Kamara, Zuhuur, II, ff. 187-8. Abdul Bokar was apparently not as enthusiastic for Amadu Biran's election as some other leaders of Bossea. ANS 13G147.38.

8. The Wan of Mbumba were known for their intra-lineage strife. Ali Ibra was deposed by his brother Biran early in the nineteenth century, while his son Sire Ali Ibra was probably poisoned by Mamadu Biran in 1849. ANS 13G139 (17 January 1850); Kamara, Zuhuur, II, ff. 183 ff.; Soh, Chroniques, pp. 80-1.

9. The new Almamy was Mamudu Malik Ba of Bababe, on the riverfront of Law. He may have taken up residence in Mbumba during the few short months of his term. ANS13G147.47,50.

10. Abdul was called a ruggiyanke (pillager) and a bess sukaaBe (flagbearer of the youth). FR, Thierno Amadou Bokar Alfa Ba, session 1 ; FR, Baba Hamidou and Yaya Lamine Agne. His name Abdul is derived from the Arabic “abd”, meaning “slave” or “servant” and used frequently in compound forms like Abdullah.

11. Kamara, Zuhuur, II, f. 40.

12. The most complete account of Ali Dundu's career is found in Kamara, Zuhuur, II, ff. 23 ff. According to Kamara, Ali came back to Central Futa at the invitation of Abdul Kader and became an assistant to the Almamy's chief minister, Eliman Hamady of Ndiafan. After becoming one of the Almamy's ministers he played a big role in the plot, and was the dominant personality of Futa between Almamy Abdul's death and his own demise in 1819. Cf. Mollien, Travels, pp. 113-14,140-4.

13. Abdul was born in Dabiya Odedji after his father had moved the family from the right bank, where they were subject to attacks from Eliman Rindiaw Falil and his Moorish allies. On the left bank, Bokar received the hospitality of the Elfeki family, who gave him land, and the Eliman Duga family, who gave him a wife. She was Jeynaba, the mother of Abdul. Personal communication of Oumar Ba, 17 April 1970; PR, Mamadou Athie; FR, Mamadou Dia, session 3; FR, Thierno Seydou Kane, session 4; FR, Farba Amayel Mbaye; FR, Sega Niang, session 4; Kamara, Zuhuur, I, ff. 220, 266, 349, and II, ff. 12,27 ff.; Raffenel, Voyage, pp. 41-2.

14. FR, Mamadou Amadou Mokhtar Wane; ANS 13B64 and 13G169, passim. His Podor wife was Lena, the daughter of Ndiak Moktar. ANS 13G141.18; Kamara, Zuhuur, II, f. 276.

15. See Chapter II, page 38, note 3.

16. Interview with Thierno Seydou Kane, 17 January 1969; FR, Thierno Seydou Kane, session 5; Carrère and Holle, Sénégambie, p. 195.

17. The information on Abdul's youth is drawn from a personal communication of Oumar Ba, 17 April 1970; FR, Demba Diawando Bokoum, sessions 1 and 2; PR, Thierno Seydou Kane, all sessions; PR, Isma Baidy Ndiaye; PR, Doungourou Gawlo Soko ; Kamara, Zuhuur, II, ff. 30,41-2.

18. Kamara, Zuhuur, II, ff. 30, 41-2; Tyam, Qaçida, pp. 115-19.1 have not been able to coordinate this battle with the archival material, but it probably occurred in late 1854 or early 1855.

19. Interview with Thierno Seydou Kane, 17 January 1969; PR, Thierno Seydou Kane, session 5. The cousin was Mamadu Mamudu Ali Dundu, who became the head of the Dabiya Kan family after Bokar's departure in 1854 and would have been a strong rival of Abdul Bokar had he remained in Futa. Cf. Kamara, Zuhuur, II, f. 30.

20. FR, Farba Amayel Mbaye. Mbaye is one of the leading oral historians of Bossea and all Futa, and resides at Kaedi. Other versions of the same event are found in FR, Bokar Elimane Kane; FR, Sega Niang, sessions 1 and 3; FR, Thierno Yaya Sy, session 2; Kamara, Zuhuur, II, f. 31. See also ANS 13G157.49.

21. ANS 13G167.93 (contained in letter of Commandant of Bakel, 18 November 1859).

22. Jiba's father Hamady was dead and Bokar consequently became her guardian. Kamara, Zuhuur, I, ff. 155 ff., and n, f. 44.

23. Kamara, Zuhuur, II, f. 65a.

24. ANS 13G163.24; Kamara, Zuhuur, I, ff. 219 ff., and II, f. 46.

25. ANS 13G157.54,120; ANS 13G168.4, 22, 62.

26. On Jauréguiberry's administration, see ANF, OM SEN.1.48 (passim); ANS 2B33bis.115; ANS 13G147.106; Annales, pp. 278 ff.; Y. Saint-Martin, “Un Centenaire oublié: Eugène Abdon Mage (1837-1869)”, Revue Française d'Histoire d'Outre-Mer, 57 (1970), pp. 153-4 (hereafter “Mage”).

27. ANS 1D23 (reports of Political Director Flize, 17 April and 13 November 1862).

28. ANS 13G140.57 (letter of the Almamy to the Governor, received in Salde 28 July 1862). Amadu Thierno Demba had apparently been recommended by Umar once before. Soh, Chroniques, p. 80.

29. The French destroyed the villages of Mbolo Biran, Mbolo Ali Sidi, Diaba (the Almamy's residence) and Hore-Fonde. It was the first time a French army had landed and campaigned in the heart of Central Futa. For French accounts, see ANS 2B33 (31 July 1862); ANS 1D23 (report of Ribell, 17 December 1862); Annales, pp. 278 ff.

30. In Futanke tradition, this battle is often confused with the 1881 battle of Dirmbodya. See Chapter VII and Kamara, Zuhuur, II, ff. 43-4.

31. ANS 13G140.58, 63; ANS 13G157.90; ANS 13G168.40-3; Kamara, Zuhuur, II, f.44.

32. Futanke tradition recalls this as the battle of Bokol while the French archives label it the encounter of Lumbel, a jeeri area a few miles away. ANS 2B33.591, 630; ANS 13G101.97; ANS 13G121.26, 27-9, 31; ANS 13G136.72; Kamara, Zuhuur,II,f.302.

33. ANS 13G121.34, 46, 48, 50; ANS 130157,93. The French-appointed Lam Toro was still Sire Geladio.

34. Ancelle, Explorations, p. 223.

35. ANF, OM SEN.4.45e (notes of Flize, 18 October 1862; letter of the Governor to the Ministry, 26 October 1862).

36. ANS 2B33.15, 34; Annales, pp. 289 ff.

37. Kanya-Forstner, Conquest, pp. 33-4,43; Saint-Martin, “Mage”, pp. 153-4.

38. Kamara, Zuhuur, II, f. 302.

39. This skirmish is called Didel in Futanke tradition. FR, Mamadou Athie; FR, Thierno Seydou Kane, session 6; Annales, pp. 297-8.

40. ANS 13G101.105, 107; ANS 13G121.63-5, 75, 77, 81-2; ANS 13G147.73-5.

41. See page 65, note 4. 5

42. ANS 13G121.97,99;ANS13G136.77-8.

43. ANS, Special File on Treaties (Treaty of 10 August 1863). Faidherbe apparently made the same promise of support to Mamadu Biran that he had given in 1859, to keep him in power permanently. ANS 13G209.184-5 (letters of Faidherbe to Mamadu Biran and the chiefs of Futa, 12 November 1863).

44. ANS 13G121.38,42; ANS 13G147.99-101,109-13. For a general view of Sidi Ely's situation and Mauritanian politics at the time, see Stewart, Mauritania, pp. 136-44.

45. Kamara, Zuhuur, II, f. 41. “Black” here has connotations of culture and religion rather than colour, especially since the Dabiya Kan were of Fulɓe background while the Wan came from a Wolof group. Cf. Carrère and Holle, Sénégambie, pp. 123 S. For the perspective of Abdul's family on these events, see FR, Thierno Seydou Kane, sessions 1,5, and 6.

46. ANS 13G157.123; Feuille Officielle du Sénégal et Dépendances (successor to the Moniteur ; hereafter Feuille), 26 July 1864.

47. In addition to the Kane references of page 67, note 3, see Kamara, Zuhuur,II, ff. 41 ff. At the same time that Mamadu Biran was invading Bossea, Faidherbe wrote to the king of Jolof to stop Abdul should he flee in that direction. ANS 3B95, p. 8 (the Governor to the Burba, 12 August 1864).

48. In Eastern Futa, the French had essentially acquiesced in Abdul's hegemony since 1862. ANS 13G23.12 (interim report to Faidherbe, July 1862). Hamady Al-Hajji Kan was the name of the new nominee, and he received the title “Almamy of Damga”. This represented a shift from the 1859 policy of looking for “anti-tooroɓɓe” candidates, since Hamady was the epitome of the tooroɓɓe reform as the son of Almamy Abdul Kader. The new strategy was tailored to the threat of Abdul Bokar, not Sheku Umar. ANS 13G140.76, 82, 88; ANS 13G169.27.

49. Duval, Colonies, p. 74; Kanya-Forstner, Conquest, p. 44.

50. Abdul's retreat to the Ferlo to prepare for a return to power was reminiscent of the action of deposed Denyanke Satigis and was called fergo (the same word that is used for migration). Gaden, Proverbes, pp. 284-6. See also ANS 13G157.-128.

51 . ANS 13G147.117-20; ANS 13G157.127; Feuille, 22 November 1864.

52 . For the public treaty, see ANS, T, Special File on Treaties (Treaty of 5 November 1864); it was published in the Feuille of 22 November 1864. For the private assurances to Abdul, see ANS 13G170.17 (19 February 1866).

53 . Faidherbe's last plan for Mamadu Biran was to make him “Almamy of Toro”. The idea was not well received. ANS 13G123.2-3, 11, 53; ANS 13G136.129; ANS 13G140.97.

54 . ANS 13G170.17 (19 February 1866).