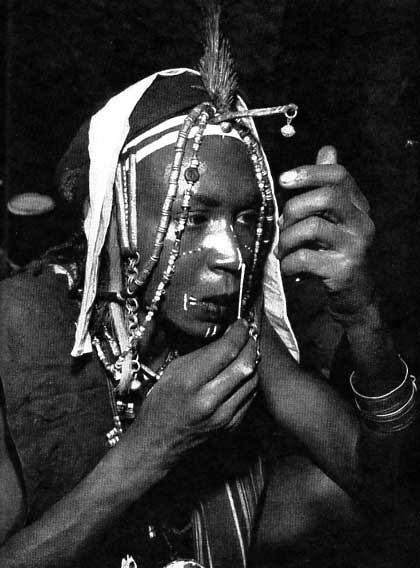

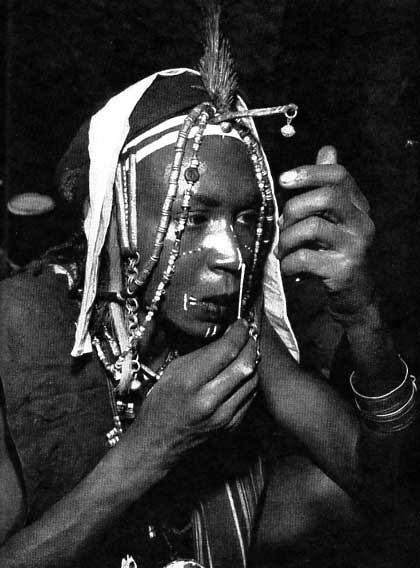

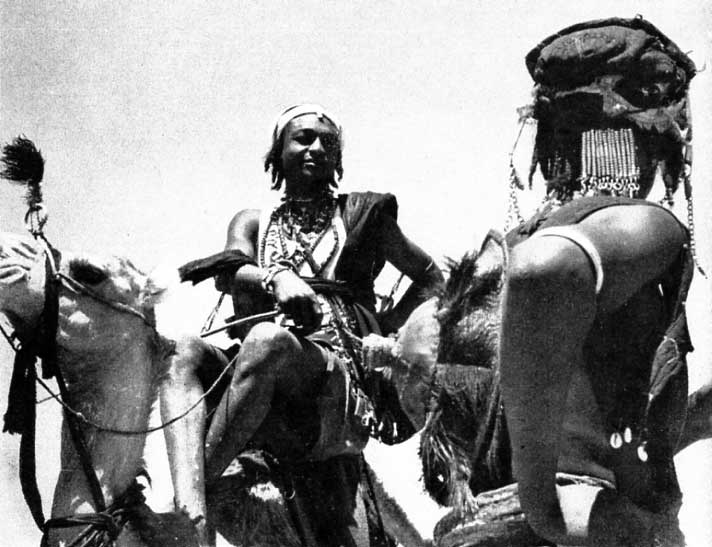

Bororo Fulani preparing himself for the jeerewol.

Photo Dominique Darbois.

Preface by Michel Leiris.

Translated by Carol F. Jopling

with the assistance of Hanna Jopling Kaiser, Laura Schultz

Vivian Cohen, Marcel Seraillier, and Willem Tissot

New York. E.P. Dutton & Co. 1974. 345 p.

« Oh, my cows, wanderers, scattered and clustered on the mountainsides and ridges, you climb, you descend, you eat, you gorge yourselves with tender grass, with short grass, with tall grass of spring and autumn, with grass that grows after a fire, oh, good grass of prairies, reeds, hollow grasses ! … »

Like many of their other poems, this one gives an exact picture of the character of Fulɓe culture. The Fulɓe not only express their basic imagery in plastic creations but also in oral literature. There are pastoral poems, epics, tales, and satires that have the prerogative of recounting the fate of men, of collecting their feelings, and of formulating and stirring them. The rhymes and rhythms of their language seem their only response to the social and aesthetic demands that we seek to find again in manifestations of art in wood, metal, or clay What does this apparent monopoly of the language disguise?

Nomads or sedentary people, miserable shepherds of hot and desolate country who graze on a sea of sand, or aristocrats and literate warriors of the rich centers of Futa-Djallon, Maasina, Liptako, Sokoto, and Adamawa, the Fulɓe do not seem to express themselves in durable forms, important for the display of their assurned initiative and talents. The technology of the nomads is pared down to the minimum.

This paring down is masked among the sedentary peoples by rich industries that give them a refined, comfortable, material foundation. But these technologies, which benefit the townspeople and even the shepherds-architectural constructions, wood sculpture, weaving, leatherwork-come to them from outside. The Fulɓe are fundamentally borrowers of techniques. Furthermore, they do not procure for themselves the practice of these techniques, the care of making the adopted models, but leave them to other castes, the first occupants of the region whom they conquered, or to foreign specialists who frequent the markets. Why then devote several pages to societies that appear materially so deprived, so little apt to create images and ornaments with their own hands?

It is perhaps worthwhile to set aside the societies that generously create innumerable objects reflecting their myths, their feelings, and their norms to examine a society like that of the Fulɓe, which stamped the local histories in the vast area from Senegal to northern Cameroun with a strong imprint. Beyond their traditional spare material forms, the importance thatthe Fulɓe attach to aesthetic phenomena is manifested through a search for beautiful language, a refined etiquette regulating attitudes, and a profound taste for nonfigurative arts like poetry, music, and song. For a rather fastidious people who are adverse to manual work, but whose aesthetic talents are expressed sufficiently in other ways, borrowing itself has its own philosophy. The few rare, permitted plastic activities, habitually considered minor, in their turn assume a breadth that cannot be ignored.

A chief of a Bambara village gave a striking description of the Fulɓe. Here, in black country, he said, they are like ants destroying ripe fruit, settling down without permission, decamping without saying good-bye, a race of eloquent rovers, unceasingly either about to arrive or about to leave, at the mercy of watering places or pastures…

This people, “loquacious roamers,” does not seem a physically coherent group, easily located in space, immediately identifiable by the characteristics of its settlement pattern on the land. In addition, the aspects of its art, varying according to indications of different places, do not elude complexity. Therefore, the difficult synthesis of this culture has never been attempted. It is always recognized, nevertheless, that aesthetic expression, which is not the monopoly of a certain type of society, reaches a very original intensity among the Fulɓe. All of those who have examined or studied them have been profoundly affected.

Fulɓe art is generally expressed in the orientation of choice and importance of the methods of the body ornamentation and the systematic uses of decorative materials, which are present in the surrounding foreign cultures. Coiffures, jewels, and clothing are constantly the objects of effort and attention. The Bororo child, naked and undoubtedly famished, who solitarily guards his herd all day long, leans, immobile, on a feeble bow of a branch, his neck ringed with a necklace of beads weighed down with pendants. Far from the villages, far into the bush of dried grass, when the wandering troop passes, the women are compared to “slender and aloof princesses” 2. Their arms are enclosed, laden with bracelets and on their heads is a large half calabash with finely carved borders from the center of which the design of the sun stands out. Indigo veils bide their bodies and are pleated under small chains and bead necklaces ending in multiform leather pendants. The young girls step forward, showing their legs ornamented with ribbed copper anklets, symbols of their status. The preoccupation with beauty breaks out everywhere, even in the fine braids of the men, which escape from their big hats with ostrich feathers. Simple details of costume or ornamentation, these heavy anklets and bell-shaped hats are still the only authentically Fulɓe artistic manifestations since time immemorial. Except for the art of the calabash, the rest is borrowed. Further, among Fulɓe townsmen these both humble and prestigious details of a traditional forgotten way of life evidently no longer exist. What then remains that is specifically Fulɓe? Perhaps the unchanged talent of arranging coiffures, multiplying ornaments, and moving with grace under a white or embroidered loincloth. The only raw material giving rise to the actual execution of an artistic style by Fulɓe hands is hair, which here replaces clay or the wood of the bombax, Made pliant or heavy, separated, braided, padded, held back, ornamented, it becomes a sculptural object. Melted butter, ground charcoal, cloth padding, bamboo slivers, amber balls, silver pieces, and beads are also indispensable elements. In lower Senegal, the different combinations of braids and coils of hair always form a precise design that bears a name 3.

In Liptako, the plaited hair reserves spaces alloted for geometric forms like diamonds, triangles, and rectangles.

Finally, in Futa-Djallon, the jubaade makes one think of a Calder mobile: the braids and loops are extended forward and sometimes backward by a sort of enormous black butterfly bow; the hair of the upper part is braided in the shape of a transparent crest stretched on an arched strip of bamboo; crowns with fine rings and pieces of silver ending in twisted cardrops add their delicate glimmer to this astonishing architecture. Like all the other arts, the hair dress varies with age, place, and social condition; nor does it escape sentimental meaning. The two little braids falling on the cheeks of the Fulɓe woman of Dori who has just had her first child are fixed under the chin with a white bead; on the nape of her neck the braids, like multiple fringes, are ornamented at their ends with white stones; this coiffure symbolizes wisdom and calm, which become the new mother of a family.

The aesthetic of jewels, clothing, domestic objects, of the dwelling with its decorations applied to architecture and furniture is-as has been mentioned-an aesthetic of borrowing, although conditioned by often tyrannical modes to which the Fulɓe society brings its exclusive imprint.

In Senegal, Guinea, Niger, Nigeria, and northern Cameroun, the Wolof, the Tuculeur, the Sarakole, the Dialonke, the Bambara, the Baga, the Susu, the Songhai, the Hausa, the Djerma, and the Kirdi provide artistic techniques and decorative themes for their Fulɓe conquerors. But over this immense Fulɓe trail, which touches the Saharan fringe in the African lands, and over these very pliant black cultures hover the Moorish and Tuareg arts. The influence of the aesthetic of Islam is taken up again, readapted, and re-created by the nomadic and the more ancient civilizations.

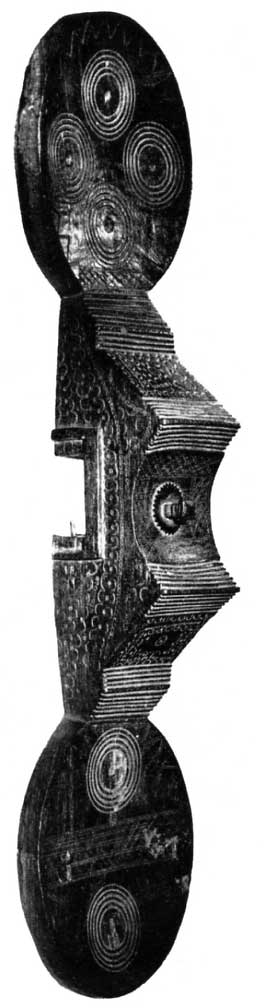

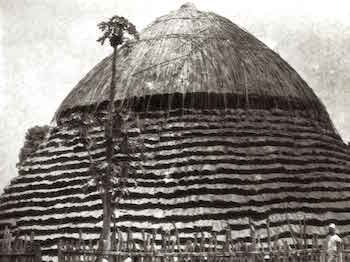

In Futa-Djallon, among the Fulɓe townspeople, one again encounters the comfortable house with a large circular veranda that contributed to the pleasing harmony of the village among the Baga. The “crinoline of thatch” 4 which covers it is made for rich men of evenly cut bunches; the tiered design thus achieved constitutes a supplementary decorative element. On these finished huts the blacksmiths put large, wood, decorated locks whose more or less stretched-out central part extends into a disk at each end. The parochial mosques also have this veranda and the springing round of the thatched roof, but this time topped with a bamboo-covered cupola. Exterior walls are rarely decorated, but the interior walls of the huts of notables and their wives are. Geometric motifs run in friezes along the walls and on the pediments of door and bed. The earth of the banco similarly presents a decoration. The technique is incised engraving made with a knife. The whole thing is then covered with a coat of white kaolin, possibly enhanced with colors, bloodred and light blue, that the finger of the artist traces in the grooves. The dominant motifs are the triangle and the crescent; stripes, circles, chevrons, lozenges, and spirals are also frequently represented. It seems evident that this decorative style, characterized by geometric patterns presented in homogeneous series, is of Muslim inspiration. But what importance should be attached to the influence, which today is masked, of the traditional decorative Mande themes to the artist, who is usually of peasant origin and who charges dearly for the sought-after exercise of his talents?

In Liptako, more than one hundred years ago, all Fulɓe notables wanted very much to exchange their straw huts for a mud-brick house like that of the Songhai of Hombori, who had come themselves seeking the protection of the Emir. The huts with high portals, vestibules flanked with benches, flat roofs with terraces, and small courtyards bordered with walls, whose doors were decorated with polychrome motifs, seemed much more convenient and prestigious than the derivatives of the pastoral straw, pointed-roof buts to the rich Fulɓe, who were in the process of becoming sedentary. In north Cameroun, the inconvenience of these constructions with terraces that were too vulnerable to the tropical rains induced the Fulɓe to copy the harmonious huts made of clay, wood, and straw of the autochthonous Musgum and Mundang populations.

The interiors of all these dwellings show bow the borrowed forms were modified according to both the practical necessities of adaptation and the desire for beauty. In the women's huts one finds again the bench where decorated calabasbes are displayed, covered or not with fine disks of polychrome basketry that they make themselves. These rows of calabashes exhibited for decorative effect by the noble ladies of lower Senegal or of Adamawa, are they not a touching reminder of a very old aesthetic tradition to be found among the nomad shepherds who are so materially poor?

Clothing itself is the fruit of numerous borrowings. The Hausa embroiderers execute their refined Niger techniques in Adamawa. Certain stereotyped patterns belong to a social elite of which the Fulɓe are only a part, and other patterns are specific to them. The interlacing motif, ubiquitous on Hausa tunics, which are sometimes overladen with designs and highly colored, is also found on the white pants of the Niger Fulɓe, bordered with several rows of colored threads.

This geometric and polychrome decoration of Islamic inspiration, which not only covers the walls of the dwelling places but also appears on the fabrics, will be encountered again in the leatherwork, itself a luxury industry reserved for the richest Fulɓe. Production of Koran cases, saber sheathes, and sandals flourishes.

Apart from these geometric groups, the pure forms-triangles, lozenges, spiraled and nonspiraled moon crescents, disks, trefoils, and crosses-are taken up by goldsmiths and applied to copper, iron, silver, gold, and even straw (imitating gold thanks to a molded wax support). These shapes, sometimes in profusion, ornament the hair, ears, neck, chests, and limbs of both the townspeople and the pastoralists. Produced, sold, peddled in the great Sahelian markets in the same manner as basketry, calabashes, embroidered fabrics, and leatberwork, these jewels, most of which are of Wolof, Tuculeur, Bambara, or Songhai origin, provide an indispensable contribution to a snobbishness of appearance, no matter how well fostered in other ways. Undoubtedly the magic virtues of the forms and the materials still count for a great deal in these jewels, for example, the beneficial powers of copper and carnelian and the good eye in the shape of a triangle add a protective content to the ornamentation.

Aside from the appeal of the foreign specialists (on whom Fulɓe regional buyers often impose their tastes or who are found to have conformed in their own styles to these special demands), the little Islamized and sedentary societies have their traditional artisans, workers of caste or servile origin, specialists in wood, leather, and clay who satisfy the demands for domestic art objects. Blacksmiths, weavers, potters of Mande or Tuareg origin, and woodworkers more or less belonging to their masters are the faithful suppliers of the Fulɓe, toward whom these artisans showed disdain. Thus, these Fulɓe societies seem parasitic to us in their work technology, but their destiny, their style of life induced them, very naturally, to multiply their aesthetic needs.

It is, in effect, normal to encounter among the sedentary Fulɓe (with the understanding that the boundaries between sedentary, halfsedentary, and nomad are only relatively rigid) this borrowed technology and tenacious adherence to artistic tenets. Among these former itinerant campers, peaceful herders who knew how to enrich, establish, and develop themselves with firmness and who fiercely protected their independence, Islam found an already prepared ground. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the successive waves of organized Fulɓe were pushed by the Holy War into the conquest and formation of large empires. Shepherds became conquerors; pagans became propagators of Islam, but they remained Fulɓe. The Fulɓe, empty-handed, always comes “from nowhere.” He moves in, establishes, goes off again, reestablishes himself, puts down roots, and spreads the tight net of his social system over the occupied country. Thus Fulɓe lords, military chiefs, and meditative wise men reign over the farmers and the artisans. For lack of a traditional artisan society, their aristocratic conceptions have to be expressed by autochthonous artistic skills as well as those of Muslim specialists of this vast area open to Islam culture. Perhaps the daughters of the local chiefs, whom the Fulɓe married at the beginning of their settlement, have aided in the diffusion of the old regional themes, in penetrating Fulɓe culture with several manual activities of an aesthetic nature.

Some of these rare, essentially female techniques may become well-known arts: the creation of the calabash lid in ronier 3b fibers in the middle valley of Niger, for example, or the decoration of the calabash itself in north Cameroun. Among the Lamidats of Garua and Rey Buba, Fulɓe women decorate calabashes, household vessels that contribute in an important way to the aesthetic quality of the trousseau. Pyrogravure and tinting allow varied decorations that range from simplified embellishments, provided, however, with chevrons or parallel stripes like the calabashes of the nomadic Fulɓe, to multiple geometric patterns with a preponderance of parallel and cross-hatchings like Hausa calabashes.

This calabash art brings us back into the world of the nomads, where it is replaced by pottery art and is not close to any other truly figurative technique, the arts of adornment excepted. The nomadic Fulɓe migrate through Niger in the Tahua, Gao, and Madua regions and extend into Nigeria among the Bororo Fulɓe, stubborn pagans, protecting their archaic pastoral traditions with pride. It is probably among these people that we will find the purest Fulɓe characteristics along with the most spontaneous application of their aesthetic feelings. It is not that the borrowing traditions are nonexistent here, because the most basic needs demand the assistance of the sedentary people. But this time the importance of the borrowings remains minimal even at the aesthetic level and develops from the extraordinary insistence of the society on elaborating its own artistic themes from a way of life that is reduced to the essentials.

The importance accorded to beauty in itself is constant in Bororo society. But it bursts in all its vital significance in the tornado season, during the festivals that unite groups habitually dispersed by the sun in the and grass, for several magnificent days of gerewol, a beauty contest at which the handsomest men of the tribe compete. All the resources of the arts, which see that the harmonious, seductive quasisupernatural appearances are created, are put into play. The body is given to the pursuit of painting and adornment to which each adds his own sensitivity. The afternoon of the festival the young men are lined up like splendid and mobile images of deities. The face is painted red, glistening with butter with outlined motifs, triangles embollished with points at the corners of the blackened lips; the head is coiffed with a cowrie headband surmounted with a long and plumy ostrich feather; from each side of the face fall strings of ram's beard, chains, beads, rings; the neck and torso, polished like precious wood, are adorned with multiple rows of white beads, leather and cowrie pendants, and metal disks, which are also found on the dyed and embroidered loincloths. A solemn song is sung on a single note (the melody having been deliberately omitted) by the young men, who are balanced on their feet placed close together. The eyes are obligatorily open wide and the grin, a wide smile blocking out the impassive face, is likewise obligatory, "the eyes and the teeth being important attributes of masculine beauty 5.

The itinerant life, from water hole to water hole, frustrates and diverts the working of material and the creating of more or less permanent forms. The Bororo's passionate love of the beautiful, in addition to dance and song, could only be expressed in the application of exceptional ornamentation for the perfecting of the appearance by the daily adornment of the body and to the most elementary domestic objects.

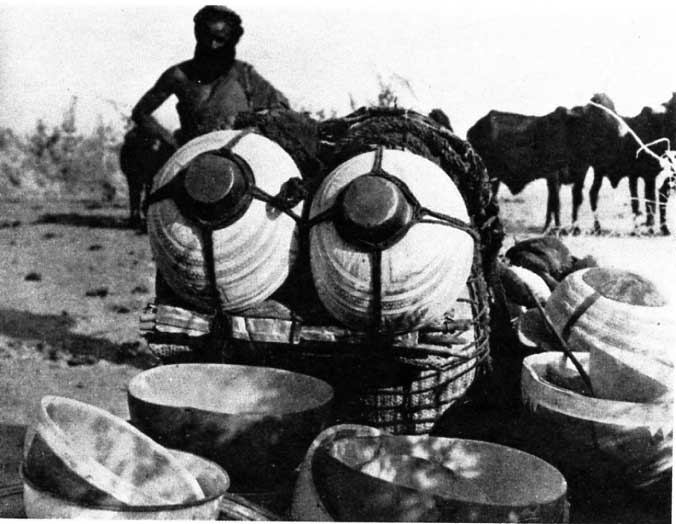

The kaakol baggage burden seems very removed from a plastic creation but nevertheless it is related to a sort of architecture, an assemblage of the humblest objects put together according to strict rules, with the precise aim of obtaining an effect of grandeur and beauty. It is a moving form of art that tries to make its way by means of harnessing:

Bumping along on the prestigious carrier ox, all this construction is the preeminent aesthetic sign for the nomadic group.

This need to display, to set apart, and to exhibit for oneself and for others the few material riches that one possesses is found again in the place reserved for the display of the catabashes at the base of a thorny semicircle that serves as a house.

On a mat supported by sticks resting on two wooden crossbars, the vessels project bellies decorated with moons, suns, and calf leads painted white. The motifs, differing from each other in secondary details—the substitution of a chevron for a line, the duplication of a band, the dentiling of a moon crescent—traditionally designate the diverse origins of the families. Today, calabashes bought in the market are engraved by sedentary artisans who follow the fashionable models, and more than one family borrows the pattern of a stranger's lineage that is to his liking. This importance of fashion, which has already been noted among Fulɓe townsmen, will be found again among the Bororo. It is always linked on the one hand to borrowing and on the other to tendencies peculiar to Fulɓe society itself. But this time these tendencies are more apparent and less smothered by external influences, as when one is established in the sedentary life, one submits to an invasion. Engraved calabashes, ankle rings, ceremonial axes for the gerewol dances, indigo-dyed fabric, long leather breeches ornamented with cowries, hats for adults in the shape of Phrygian headdresses—all are of Bororo style 6.

Here, among these tireless itinerant people of Sahel, accomplished shepherds, but poor creators of technologies, it is necessary to look for the most authentically aesthetic attitudes, which do not result here in any formal realization of major importance for art in general but which exploit, to an intense degree, all the most spontaneous resources offered to the human spirit by nature and the social life. The sun and the moon in semicircles, the triangle that represents the notch made in the ear of a young calf (and by extension the calf itself), the leads (images of the cords to which the calves of less than two years are attached, true symbols for the Fulɓe of the ancient bond between man and cattle)—these provide a decorative geometry that does not break the schematism of the very rare human representations. Because of the constant attention that it is necessary to invest in the surrounding world, where one discovers each day a strange sector and thousands of daily fears, these figures attain greater value and crystallize in immutable forms. This decorative geometry persists in the art of the sedentary Fulɓe stimulated by Islam. It will appear among the artists making use of techniques of different origins intermingled with patterns with new meanings. The leads and the suns are integrated with exuberance into an embellishment essentially connected to the priority of the architectural pursuits developed by the characteristic Muslim urban style of life. But the sources of this aesthetic inspiration, glimpsed in the Bororo world, should not be forgotten.

In contrast to the peasant groups who cling to the earth from which they draw their deities and which they people with their dead, for whom their artists must carve wood images in order to keep them alive, the nomadic Fulɓe, followed by the sedentary Fulɓe, who are encumbered with neither an ancestor cult nor a weighty technological and political apparatus, have found an infinite number of chances for aesthetic invention in their style of existence.

Notes

1. This chapter appears in Cahiers d'études africaines, IV, 1er cahier, Paris, 1963, pp. 5-13, fig.

2. Henri Brandt, Nomades du soleil, p. 17. This author made a very beautiful film on the Bororo Fulɓe that has the same title as the book.

3. For example: kyara coco, “branch of the coconut palm”; bole, “baobab”; letti, “mat”; gati dior, “bed”.

4. Expression used by G. Vieillard in his Notes sur les coutumes des Peul du Fouta-Djallon. This writer, who lived for many years among the Fulɓe of Futa-Djallon, passionately devoted himself to the study of their culture, in particular to their oral literature, “songs of griots, praises, or insults to heroes or women, sayings on the famous cities.”

*Translator's note: borassus palm tree.

5. The observer, Z. Estreicher, adds that during the performance of a song, one or two old women pass in front of the singers “to make fun of those who are not handsome.”

6. Marguerite Dupire helped us a great deal in the establishment of this part of our study by allowing us to examine her then unpublished article, “La Place du commerce et du marché dans l'économie des Bororo (Fulbe) nomades du Niger.” This article appeared in Etudes Nigériennes, III, I.F.A.N., Niamey, 1961.