Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1985. 420 pages

The victory at Kholu in January 1855 opened the door to the conquest of Karta. The raids of February provided an important cache of weapons. By April Umar stood in the Kartan capital of Nioro, where he wrote letters to Fuuta-Tooro, Masina and the Moors announcing his victory over “paganism” 1. The detail of the internal narratives and the intensity of the rhetoric about “filthy pagans” and “obedient martyrs” suggests how important this campaign was. These internal sources, including the short Fulfulde and Arabic chronicles 2 together with some external perspectives collected in the early colonial era, form the basic documentation for the Karta campaign.

The Bambara state was much larger, more heterogeneous and more powerful than Tamba. It was not quite as awesome, however, as its external reputation avowed, especially after its Senegambian connection had been removed. Shaikh Umar knew this well and took advantage of every weakness in a brilliantly executed campaign.

The ruling Massassi clan, answering to the famous Bambara name of Kulibali, exercised control over about 50,000 square kilometres and perhaps 250,000 people 3. Most of the region fell within a sahelian environment which averaged between 60 and 80 centimetres of rainfall per year. The quantity and distribution varied greatly, creating periodic famines and regular shortages of grain during the “hungry season”, which extended from about April to the October harvest. The concomitant advantage of a dry climate was its suitability for raising livestock, which contributed to the political economy in the form of meat, milk, and hides, beasts of burden for transport and mounts for cavalry warfare. Karta was an important exporter of the Barb horse to the states of Senegambia and the Upper Niger 4. It also functioned as part of the desert-side economy, where Moorish caravans brought salt and livestock to market and exchanged them for the slaves, kola, gold, and cloth of the south and south-west Cloth was the principal currency, marking Karta as part of the Senegambian commercial zone rather than the cowry dominated Middle Niger 5.

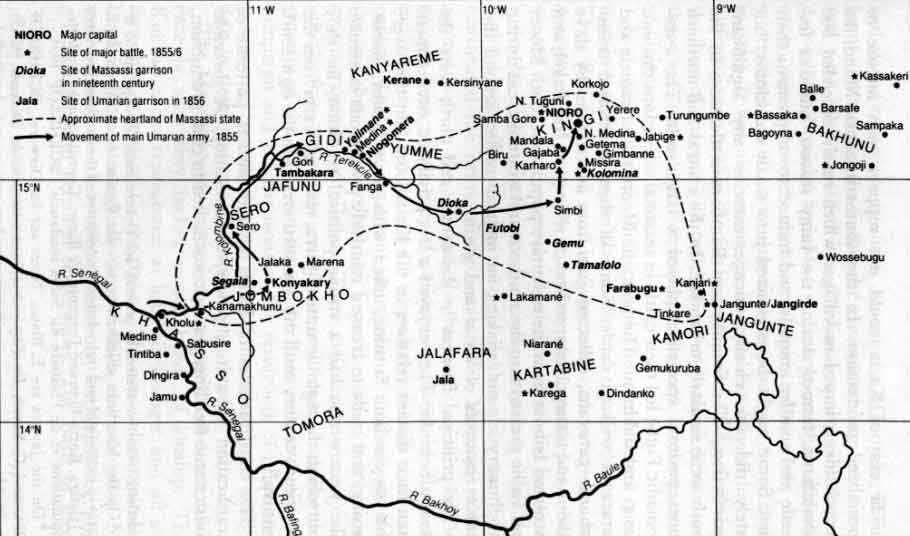

Map 5.1 Karta: Western and Eastern Theatre

The western end of the region contained its most important physical feature, the Kolombine River and its tributaries. This system, drawing water from the more elevated plateau to the east, maintained a high water table and a floodplain agriculture similar to that of Fuuta-Tooro. The rainfall harvest came in the fall, the floodplain one at the end of the cool dry season, around February. The predominantly Soninke population used this agricultural advantage to launch themselves into trade, maintain a rich craft tradition, purchase slaves to perform most of the farming, and develop towns of several thousand inhabitants. Density approached thirty persons per square kilometre. Kanyareme, Gidiyumme, and Jafunu, the three societies which exploited the Kolombine, resembled the organization of Gajaga: competing lineages, large settlements, a considerable slave population, and little central authority 6. The rest of Karta could not support such intense or specialized production. In the southern zones Mandinka households, grouped in villages which rarely exceeded 500 inhabitants, farmed during the rainy season, raised a few cattle and smaller animals, and hunted to supplement their diet. Some might be organized into small chiefdoms, but rarely did the chiefly lineage exercise any significant jurisdiction 7. The Soninke and Bambara settlements in the south were similarly organized. In the central and northern zones pastoral specialists played a larger role. The semi nomadic Fulbe led their cattle in seasonal migrations through Kingi and Bakhunu. The nomadic Moors raised camels and horses as well as cattle. Some of them controlled transSaharan caravans, collected gum from acacia trees by slave labour and transported it to French river ports like Bakel, and extracted tribute from the sedentary population. Both Moors and Fulbe pressed into the southern and western areas during the “hungry season”, making for intense conflict around the scarce resources of water and grain.

The principal farmers in the centre and north were the Jawara Soninke. They enjoyed a less privileged environment than their distant relatives in the Kolombine, but they were able to combine farming, often with slave labour, horse raising, and trade to create a relatively prosperous existence. The Jawara also had a strong political tradition, for they controlled, through the state of Jarra, much of Karta from the fourteenth century until the Massassi arrival in the eighteenth century 8.

The constituencies of Karta shared similar patterns of stratification by status, power, and vocation. A threefold division into free lineages, castes attached to craft production, and slaves existed everywhere. Among the Mandinka, Bambara, and some of the Fulbe, the slaves were few in number and were often absorbed into the lineages of their owners. Among the Soninke and Moors, absorption often did not occur, especially where slaves were separated by work, place of residence, and even physical appearance from their masters. It was also among the Soninke and Moors that the differentiation within the free category was sharpest, taking the form of lineages with political and military authority and those with clerical and commercial vocations, on the pattern of Gajaga and Gidimaka.

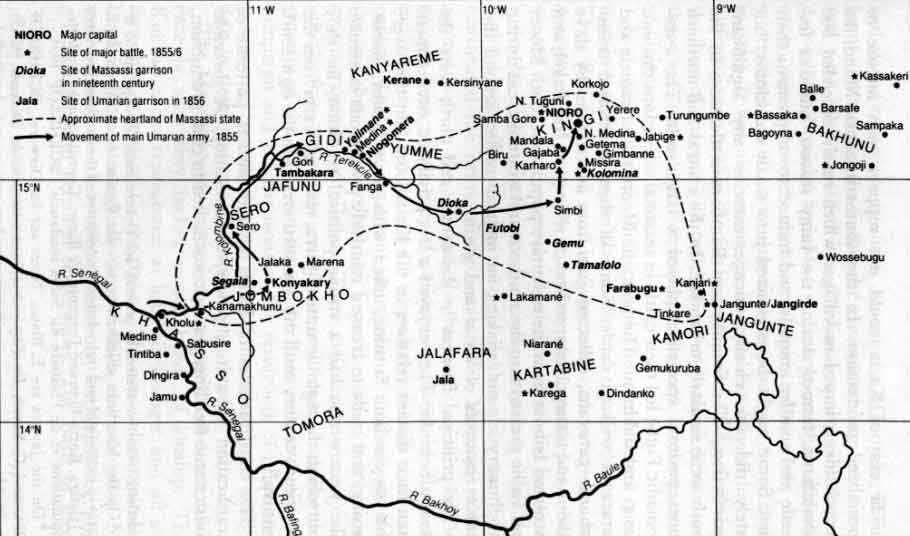

Into this welter of ethnic groups and social strata came members of the Massassi clan in the mid-eighteenth century. They fled from civil war in Segu and took refuge in the sparsely settled south. By diplomacy and force they acquired control over the more densely populated central and northern zones by 1800. These zones, running in a belt from the Kolombine valley in the west to Bakhunu in the east, constituted the heart of their state. The Massassi raided against Segu to the east and Tamba to the south, while in eastern Senegambia they established a network of alliances, but in none of these regions did they try to establish territorial control. The most important instrument of their success was the one they had developed in Segu: the tonjon or cohort of crown warriors and officials. These civil servants, recruited initially from slaves captured in war and free men seeking the security of the state, constituted the main military units on campaign and the garrisons at the residences of princes in peacetime. Upon the death of the king the tonjon played a large role in determining succession to the throne 9.

The Massassi were particularly susceptible to tonjon influence because they lacked strong bonds of kinship. The Kulibali exiles represented at least six lineages and all six furnished candidates for the throne. The contenders typically lived in large, strategically located villages surrounded by their cohorts, members of blacksmithing, leathermaking, and griot guilds, and personal bodyguards. The basis of their existence was predatory and parasitic: tribute from subjects, tolls on trade, and booty from war. The booty included male captives, who might be taken into the army or sold to the merchants for labour or export, and women, who were usually distributed to members of the royal lineages, whose numbers and succession problems were thereby increased. The Massassi made little effort to integrate the indigenous chiefs and elders into the state or its rewards 10.

In religious terms the Kulibali and their courts practised an amalgam of Bambara rituals symbolized, in the minds of Europeans and Umarians, by altars and objects called bori which were designed to ensure the fertility of women and the soil. A royal priesthood maintained temples at the main courts. Muslim clerics were welcome, but they did not possess the prestige and authority of traditional practitioners. Most were Soninke connected to the caravans which moved between savannah and desert, Niger and Senegal. They were in no position to challenge the enslavement of Senegambian Muslims or other practices condemned in Islamic law 11.

Massassi hegemony was unpopular but relatively uncontested until the mid-nineteenth century. The control of the Kolombine bread-basket and the approaches to the Upper Senegal, with its resources of gum and cloth, was particularly tight, and it was accomplished at the expense of the large Khasso state of the eighteenth century. In the east the Kulibali expanded at the expense of Segu in the 1820s, but they lost the initiative to the new Muslim regime of Masina in the 1840s. To the north they never mastered the Awlad Mbark Moors, whose camelry and cavalry ranged too quickly across the steppe, nor did they completely subdue the Jawara. The Jawara revolted again in the 1840s and continued their struggle for autonomy until the Umarian invasion. That struggle seriously weakened the regime 12.

The historian, thanks to the forced residence of the French explorer Raffenel in 1847 13 can obtain a fairly detailed picture of Karta on the eve of the jihaad. The Fama or king was Mamadi Kanja, a man of some age who appeared indecisive in the face of challenges to his authority. He moved his capital from Yelimane in the Kolombine system to Koghe in the north west, and finally on to Nioro in the north. The last move was designed to approach new caravan routes and markets and gain greater leverage in the struggle against the Jawara, Awlad Mbark, and Masina. But Mamadi had little control over his cousins and their scattered garrisons in the centre. His troops were equipped with guns, but they were full of rust, dirt, and holes and they were fired with powder of poor quality. In the opinion of Raffenel, “they posed a danger only to those who fired them” 14.

Table 5.1

Umar plotted his strategy with the help of his principal Soninke adviser, Alfa Umar Jakhite, members of the royal Khassonke lineages of Medine and Sero, and some Bambara prisoners and defectors 15. The route chosen was the Kolombine valley, virtually dry in early February, and the first stage was Moriba Safere's kingdom of Sero. This brought the troops to Jalunu, the richest of the Soninke societies and the one best able to provide grain during the approaching “hungry season”. Jafunu was divided into competing villages, lineages, and military and commercial classes. It was accustomed to political overlords and had no reason to prefer a Massassi master to Umar. In fact, some of the Muslim Soninke responded instinctively to the message of jihaad even though it was not prominent in their Islamic tradition. Umar established his headquarters in the two most important towns, Tambakara and Gori 16.

The Massassi employed the defensive strategy which had proven successful in their earlier conflicts with Segu and Masina. They withdrew to the walled towns of the interior on the assumption that the fortifications would withstand assault and their assailants would desist in the face of the hot dry season. But they reckoned without the determination and weapons of the Senegambians, the food supplies of Jafunu, and their own weakness and fragmentation. Each Massassi lineage defended its own garrison and the jihaad was consequently able to concentrate first on Yelimane, where the Denibalen held sway, then on Medina, where the Siralen were predominant, and finally on Nioro, the centre of the Monsire group represented by the reigning king 17.

After his victories at Yelimane and Medina in mid February, Umar moved east to Fanga, a strategic pass at the entrance to the plateau. Here he camped for six weeks to allow the news of his triumphs to have its effect on the local population. He soon received delegations of submission from the Fulbe of Karta under a certain Wulibo, some Wolarbe Fulbe of Bakunu under Sambunne, the Soninke of Gidiyumme, the Jawara Soninke and some small Bambara and Moorish fractions. Wulibo quickly became a trusted adviser and emissary, helping to persuade some of the remaining Massassi not to resist 18.

As he moved towards Nioro in early April, Umar received oaths of allegiance at each step of the way. At a village called Tagno he accepted the submission of an important Massassi prince. At Dioka, the centre of the Bakari Massassi lineage, he found only deserted homes. Finally, on the outskirts of the capital, he received the submission of most of the surviving Bambara royals. Mamadi Kanja swore allegiance and took the necessary steps to become a Muslim. The internal narratives couch their relief and triumph in terse language: “Mamadi Kanja swore allegiance to Umar. His head was then shaved and he was given a bonnet. Each pagan who made the profession of faith had his head shaved and received the cap” 19.

Umar, now confident of victory, massed his troops, marched into Nioro on 11 April 1855, and claimed the capital of “paganism” in the name of Islam. To underscore his claim he ordered his new Bambara subjects to bring their household shrines to the public square where, like Muhammad in Mecca, he smashed them to bits 20. He then established the guidelines for personal behaviour in the new order: the profession of faith, the shaved head and cap, and the reduction in the number of wives to four—the maximum allowed under Islamic law. This regulation struck directly at the Bambara aristocracy and their accumulation of women, many of them Senegambian, from victories in war 21. Mosques would be built throughout the land and instruction offered in the new faith. In about three months the Shaikh had accomplished what no previous Fulbe jihaad had seriously considered, the destruction of the superstructure of the Karta state and its hegemony over eastern Senegambia.

In his February letter to the Muslims of St Louis, Umar was correct in claiming that his troops were not just “the people of Fuuta-Tooro but rather those who wage jihaad against the enemies of God”. Many of the soldiers, perhaps a majority, did hail from the middle valley. The main battalions were now named Ngenar, Yirlaaɓe, and Tooro, after the three provinces of Fuuta which had furnished considerable numbers of recruits 22. But the infusion from Ɓundu was large, and formed a significant part of the battalion of Tooro, since the ancestors of the Sisibe had come originally from that area. The Khasso forces were also considerable, especially Moriba Safere's men from Sero and troops attached to the Jallo lineage of Medine. Under the leadership of Kartum Sambala, the Medinans hoped to regain the control of the fertile and strategically located north bank which their ancestors had exercised earlier. The talibe from Fuuta-Jalon who had played such an important role in previous campaigns no longer formed a separate contingent, but fought with Yirlaaɓe 23. Alongside this force the Shaikh created a new battalion of sofas called the jomfutun 24. The male prisoners captured at Kholu formed the core of this contingent, and other Bambara and Mandinka infantry from old tonjon units were added later.

This large, diverse, and quickly recruited army had obviously not been welded into a unified fighting force. Umar had neither the time nor the capacity to form his new troops in the pattern of Dingiray or instil an ideological commitment to jihaad. He had mobilized the talibe by working through the traditional systems of patronage in Senegambia. He had expected to monopolize the distribution of booty, but he was soon obliged to allow the talibe to keep whatever they obtained from battle or confiscation. Some of them planned to return home for the rainy season, and it would take substantial material satisfaction to persuade them to stay 25. The jihaad was acquiring a momentum of its own, beyond Umar's control.

In these conditions the Shaikh began to form a personal bodyguard out of some of the sofas, his trusted Hausa servants and some old companions from the Dingiray community. This group operated within the jomfutun on campaign and at the palace in times of peace. Umar could be certain of their loyalty, he could appropriate all of their booty for the state treasury. In time this inner circle would arouse the ire of the talibe 26.

While the scale of the jihaad prevented the intimacy of earlier days, Umar was still widely visible and a source of inspiration to his men. On the eve of the battle of Yelimane, the Segu chronicler painted this image of the leader of the jihaad:

The unique one brought joy to the talibe,

drawing their attention to the eternal promises and dangers.

The traditions [of the Prophet] were explained.

He preached, filling their hearts with hopes for the after life,

Making this world seem like a treadmill, the other like the desired goal

The Differentiator [Umar] said: 'Hasten to battle, when the armies meet

Whoever devours the space between them will have the victory 27.

The widespread confidence in the Umarian mission and the reality of Paradise helped galvanize the army and was probably a decisive factor in the victories.

The importance of Umar's presence was also demonstrated in natural crises. On a scorching day in April, between Fanga and the triumphal entry into Nioro, men and mounts were beginning to droop and drop from thirst. On some low ground Umar asked his soldiers to search for wet earth and then dig down:

From beneath the tree there gushed forth water to fill the place. They drank and washed themselves, they watered and washed their animals. They were astonished at the purity and sweetness of the water, and called that place the «Stream of Help» 28.

Almost all of the internal chroniclers cite this event as one of their leader's main miracles. For chroniclers and talibe, it was testimony to his empowerment by God and their resulting election.

In contrast to Bambuk, Umar clearly intended to rule his new territory. He established his headquarters in Mamadi Kanja's palace in Nioro and began to accumulate there the gold, cloth, and other goods that he had been sending to Dingiray. He dispatched a trusted lieutenant, Cerno Jibi Ban, to build a fort at Konyakary. Cerno Jibi was responsible for overseeing the movement of men and material from Senegambia and maintaining communications with the south; to accomplish this he used the commercial centre of Gunjuru, a few miles from Medine on the south side of the Senegal 29. In the vicinity of Nioro Umar installed a few recruits with their families. Beyond these elements of administration Umar did not go. Most of the indigenous groups who submitted to his authority were granted considerable autonomy. They were called tuburu, “those who have converted” 30. They retained their chiefs and land, but were required to give hostages as a token of their loyalty. They would be asked to furnish contingents to the army and would only be allowed to keep half of the booty, rather than the four-fifths of Islamic law or the even larger portion which some talibe kept. The Massassi, as the old ruling class and leaders of the only resistance Karta had thus far offered, received harsher treatment, but they were not executed for the most part. Consequently they were in a position to lead the summer revolt which dramatically challenged the jihaad and changed the nature of its rule.

The symbol of the Bambara grievances was the limitation on wives. Members of the royal family were accustomed to an abundance of wives as a demonstration of their prestige and a means of maintaining alliances. Mamadi Kanja reputedly had fifty. The Massassi obviously did not accept the Islamic rationale for the limitation. As one prince trenchantly remarked, “This is not true religion, they want our women for themselves.” 31. The underlying issue was the reversal of fortune. In the new order of things the Kulibali would be expelled from their palaces, stripped of rank and wealth, closely watched, and reduced to the status of neophytes in Islam. This went against all their training and expectation and it produced a temporary unity that had not existed before. The Massassi, taking advantage of their knowledge of the terrain, the partial dispersion of the Umarians and the element of surprise, launched a revolt in late May, first in the northern and subsequently in the central and southern zones.

After sending their families to the south, they attacked the jihadists simultaneously in Nioro and Kolomina, a Bambara centre just south of the capital. In both towns the invaders had taken over the old Massassi palaces and implemented the new demands. Their isolation from the indigenous quarters and the countryside provided ample opportunity for plotting the revolt. In Nioro the Bambara held the Umarians hostage for two weeks, cutting off supplies of grain, meat, and water. Some of the talibe panicked. Without Umar's approval they massacred about 400 people who had been enclosed with them and who were suspected of harbouring spies. Their superior firepower finally enabled them to break the siege and kill a substantial number of the Massassi. Meanwhile, a Bambara prince named Gelajo Desse rose up in Kolomina against Alfa Umar Baila, to whom the Shaikh had given the responsibility of applying the new order. Alfa Umar lost a host of soldiers and remained a prisoner in the palace until Nioro detachments liberated him in mid-June. The words of the Segu chronicler reflect the bitter turn that the conflict was now taking: Gelajo Desse, “the immoral one, was killed, dragged, thrown into the clay pit, the bastard who will never be cleansed” 32. In late June the Umarians pursued the survivors to Gimbanne where they won another major but costly victory.

At this point the Bambara shifted the combat to the south where the rains, a more precipitous terrain and a more friendly local population would work in their favour. The swollen streams helped neutralize the Umarian advantage in cavalry; the moisture affected the gunpowder, while poor discipline and communications prevented the jihadists from co-ordinating their efforts in one strategy. At Kanjari in July they were badly mauled. At Karega in September they were on the verge of elimination when Umar brought in new troops and won a crushing victory. The booty was enormous: 10 to 12 prisoners per talibé according to Mage's informants 33. The army then eliminated the remaining pockets of resistance and drove the survivors either into Fuladugu, an area to the south-east under Segu domination, or the Upper Senegal, where Faidherbe offered refuge. When the troops returned to Nioro in late 1855, the southern zones resembled scorched earth.

Umar left patrols in the south. He renewed his charge to Cerno Jibi to watch over the south-west. He sent a small garrison to the western Soninke district of Kanyareme and a more important group to Bakunu in the east. In Nioro the Shaikh built his own palace out of stone, in the Dingiray pattern. His architect and engineer was Samba Njay Bacily, a former mason in St Louis who had enlisted at Farbanna the year before 34. In the treasury inside the new palace Umar began to lay in stocks in anticipation of a severe “hungry season”.

The requirement that the tuburu turn over half of their booty to the treasury did not sit well with the Jawara Soninke, who constituted the most precious of the local auxiliary forces. Most of the Jawara lived in Kingi, the northern province which extended from Nioro to the east. In joining the jihaad they had expected to end their long struggle against the Kulibali and restore the autonomy and power which they had always prized. In exchange for troops they assumed that they would be free of tribute to the new regime.

At the end of 1855 the Jawara refused to hand over the booty acquired against the Massassi. They withdrew from the Nioro area to a cluster of villages around Jabige, 30 miles to the east. Under a war leader named Karunka, they began raiding the cattle and trade caravans heading for the capital. On one occasion, as the “hungry season” of 1856 approached, they went so far as to kill and enslave some talibe 35.

By this time a Masinanke army had moved into northern Bakunu. Hamdullahi had watched the jihaad in Karta with growing alarm, especially after Sambunne, a former vassal, had enlisted and helped extend Umarian influence to the east. The Caliph did not control Bakunu, but he did have a strong proprietary interest born of numerous raids and several transfers of population to Masina. It was with this concern that he dispatched a large army of surveillance under one of his leading generals 36.

An alliance of Masina and Jawara might spell doom for the jihaad. Umar accordingly moved against the Soninke in June. His cavalry surprised them at night, devastated their villages around Jabige, and drove the survivors into Bakhunu. There the Umarians joined up with their Fulbe allies under Sambunne, while the Jawara linked their cause to some disaffected local groups, some Awlad Mbark factions and possibly the Masinanke. The jihadists suffered a defeat at Bambibero, but they quickly regrouped under Umar's personal command to win a resounding victory at Bassaka. This battle brought in considerable prisoners and other booty and seemed to break the back of the resistance 37.

At this point the Soninke traditions provide precious insight into the changing character of the jihaad. According to an account collected in the early twentieth century, Umar demanded 300 Soninke soldiers in addition to those already captured. The Jawara complied and Karunka himself surrendered. Alfa Umar Jakhite, the Soninke cleric from Ɓundu who had played such a large role in the Karta campaigns, then informed Karunka of plans to execute him, and the war leader escaped with a few followers to the south. A furious Shaikh Umar gave the orders for what the Jawara remember as “the day of those seated in the sun”. The 300 soldiers were exposed for hours to the gruelling June heat, without food or drink, and then were decapitated by the executioner's sword. This incident was ample evidence of the growing bitterness between supporters and foes of the jihaad 38.

By this time the Masinanke and Umarian leadership had exchanged a number of delegations and messages about their relative rights in Bakhunu. The Shaikh claimed that Hamdullahi was interfering with the fulfillment of the jihaad. The Masinanke general retorted that Bakunu was already under Islamic hegemony. In August Umar decided to end the inconclusive debate and sent Alfa Umar Baila to surprise the rival camp at Kassakeri. After intensive combat the superior weapons of the jihadists prevailed. The toll was heavy on both sides. The battle helped crystallize the growing antagonism between the two champions of Islam. In the short term it battered Masinanke prestige and cleared eastern Karta of a formidable foe 39.

At the same time it provided Karunka a respite to organize resistance in the south, in the same area where the Massassi had briefly succeeded the year before. The rain made cavalry movements difficult. The Jawara leader fashioned an alliance with several local groups and attacked the Umarian garrison which had been posted at Farabugu. Some jihadists from Nioro contained the attack until the main army could arrive from Bakunu. About one week after Kassakeri the Umarians liberated Farabugu, drove the enemy east and won a decisive victory at Jangunte. Jangunte ended Jawara resistance just as effectively as Karega spelled the end of Massassi efforts the year before. But it fell within the traditional jurisdiction of the king of Segu, and Umar consequently dispatched a delegation to reassure the Fama that he harboured no designs on Segovian territory. In his weakened condition he could ill afford opposition on another front. He nonetheless installed a 1,500-man garrison, under his trusted Hausa disciple Abdullay, and rebaptized the town as Jangirde, “the school”. Then he returned to Nioro to lick his wounds and reflect upon next steps 40.

D. The Effects of Revolt and Repression

The struggles of 1855 and 1856 revealed the weaknesses of the Umarian army and administration. The lack of discipline of the troops was apparent: they panicked, they disobeyed orders, they displayed cruelty and greed. Their Shaikh was not consistent: at times he admonished them, at times he gave the cruellest orders of all. In contrast to his position above the fray in Farabanna, he was now rushing about like a fire-fighter snuffing out the latest blaze. Had the French mounted a concerted effort to block the flow of arms and aid the rebels, the jihaad might have had the same fate as the Massassi regime in 1855. The reputation for invincibility established from Dingiray to Nioro was destroyed. The reputation as liberator from the Bambara yoke was, at the very least, badly tarnished.

In military terms, the Umarians were still more than a match for any opponent in massed combat and open terrain. They maintained a decided edge in fire-power by circumventing the French embargo and obtaining British supplies from the Gambia. But the requirements for ruling Karta were much more exacting. Few of the Senegambians had military experience that went much beyond riding and raiding, and fewer still had experience in the administration of subjects of a different culture or the implementation of Islamic law. The Shaikh had always stressed the dismantling of “pagan” institutions rather than the creation of Islamic ones. In the short period before the revolts he gave no training to his lieutenants about how to run the territory and integrate the population into the new regime. Once the revolts began he had to devote most of his energy to suppression. It is little wonder that some of his subordinates, isolated in garrisons in a vast and strange land, grew accustomed to slave labour, confiscated food supplies and generally took advantage of the civilian population. In these instances the local inhabitants perceived the new order as arbitrary, foreign, and similar to the garrison state which it had replaced.

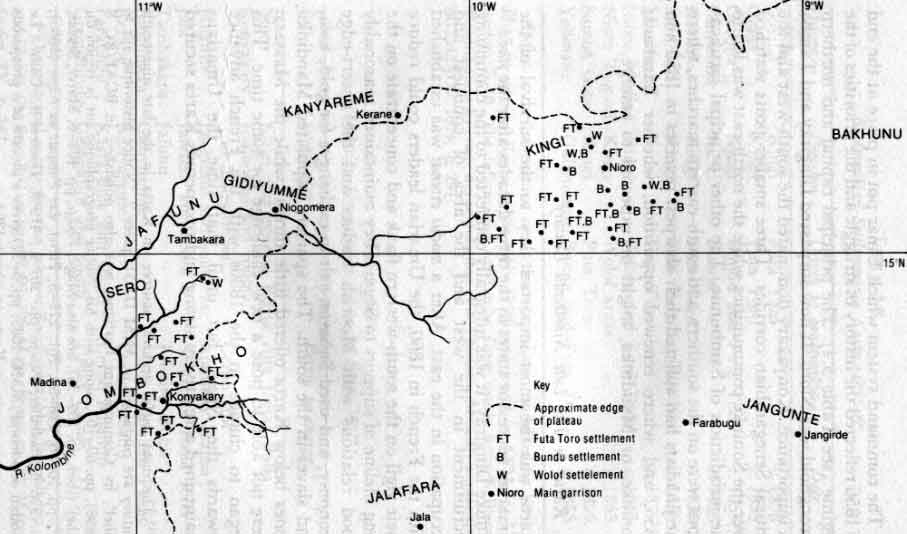

The Karta campaigns disrupted the agricultural cycle for two years and took a heavy toll of lives on both sides. On the basis of very rough but probably conservative estimates (see Table 2), the Umarians lost about half of the original force which marched up the Kolombine valley. The desertion of some Bundunke and Khassonke recruits further diminished their strength. Umar recognized the problem early on. Even before the Massassi revolt he sent recruiters back to Fuuta-Tooro, and he maintained a constant pressure on all of his Senegambian sources throughout 1855 and 1856.

In the course of the two years the conduct of warfare had grown more harsh. Male prisoners were now routinely executed. Women and children were enslaved. Neutral villages were no longer spared. Hand in hand with the escalation of warfare went an intensification of the rhetoric. In the internal narratives the Umarians who died in battle were martyrs who departed immediately for Paradise. The local allies who remained faithful were generous, valiant, and obedient to God. Those who revolted were betrayers of Islam, filthy bastards who deserved execution. This language corresponded to a psychological dehumanization of the enemy which helped excuse the increased violence.

The Bambara equivalent to the Umarian rhetoric is harder to find, but it does emerge in an interesting episode in the French archival record of 1883. In the presence of the French commander at the Kita fort, a member of the Massassi lineage encounters one of Umar's sons who had become governor of part of Karta:

Mari Sire was a brother of old Dama Massassi. Nuhu … was a son of al-hajj Umar. They did not shake hands.

— Good morning, Mari Sire. I wanted to see you because it is said you are one of the bravest Bambara.

— That is possible. I am not brave in comparison to the French, but I am against the Tokolors [sc. Umarians] and I will gladly run my sword through your body.

— Why speak that way? I'm not waging war. Don't forget that you are a pagan and I am a son of al-hajj Umar. And above all, don't smoke in my presence. Remove your pipe: the smell makes me sick.

— I prefer to keep smoking. If you want me to set it aside, remove your beads. It irritates me, seeing those beads around your neck. And if you're not waging war, it's only because the French prevent you.

— Now look here, Mari Sire, I can be your friend, your daughter is my wife.

— Never, my daughter is not your wife! You stole her, she is a prisoner. As long as she is with you I will never regard her as my daughter…

The officer then stepped in to separate the two men 41. For the Bambara, the jihadists cloaked their oppressive regime, symbolized in the taking of women, behind ridiculous rituals like fingering beads.

Despite his prominent role in combat, Umar became more isolated from his troops. When he was not out campaigning, he was usually surrounded by his jomfutun in Nioro. The Tijaniyya teaching which had loomed so large in earlier years virtually disappears from the internal narratives. Alfa Umar Baila and some other Senegambians were still active in the inner circle, but a number of other talibe had died in battle or been assigned to garrison duty elsewhere. In their place one could now find Karta inhabitants who had sworn and maintained allegiance to the jihaad throughout the revolts:

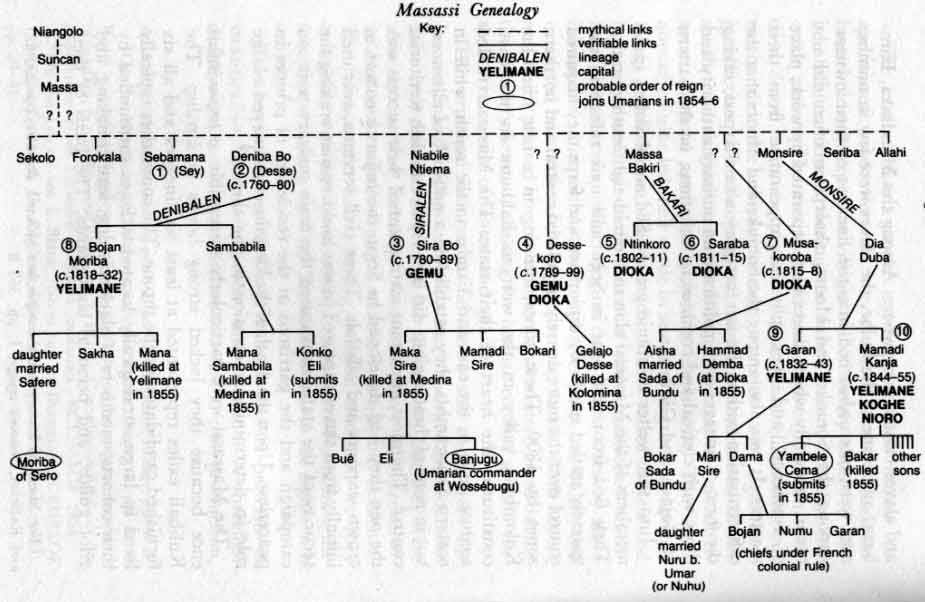

Umar encouraged some of his talibe to settle on the land around Nioro, especially in the villages vacated by the Jawara during the revolt of 1855-6. The result was to give a strong, Senegambian Fulbe character to the region and to provide the capital with added insurance against revolt or invasion. On the basis of archival and oral sources, the following settlements can be cited:

Table 5.2 — Approximate Casualties and Prisoners in The Karta Campaigns, 1855f

| Date | Battle |

|

|

|||||

| Statement on killed | Est. or Figure | Statement on killed | Est. or Figure | Statement on prisonners | Est. or Figure | |||

| Conquest | 1/55 | Kholu | some | 100 | heavy | 500 | 1,730 | 1,730 |

| 2/55 | Yelimane | some | 100 | very heavy | 1 ,000 | heavy | 500 | |

| 2/55 | Medina | heavy | 500 | heavy | 500 | heavy | 500 | |

| Sub-total | 700 | 2,000 | 2,730 | |||||

| Massassi Revoltand 1855 | 6/55 | Nioro | heavy | 500 | heavy | 500 | ||

| 6/55 | Kolomina | heavy | 500 | heavy | 500 | |||

| 6/55 | Gimbanne | heavy | 500 | heavy | 500 | |||

| 8/55 | Kanjari | 1,000b | 1,000 | heavy | 500 | |||

| 9/55 | Lakamane | some | 100 | heavy | 500 | heavy | 500 | |

| 9/55 | Karega | 1,000c | 1,000 | heavy | 500 | very heavy d | 2,500 | |

| Sub-total: | 3,600 | 3,000 | 3,000 | |||||

| Jawara Revolt and 1856 |

|

Jabige | minimal | heavy | 500 | |||

| 6/56 | Kingi raids | heavy | 500 | heavy | 500 | |||

| 6/56 | Jongoji | heavy | 500 | heavy | 500 | |||

| 6/56 | Kefebugu | heavy | 500 | |||||

| 6/56 | Bambibero | 1,500e | 1,500 | minimal | ||||

| 6/56 | Bassaka | fairly heavy e | 200 | very heavy | 1,000 | heavy | 500 | |

| 7-8/56 | Jawara offensive | fairly heavy | 200 | minimal | ||||

| 8/56 | Kassakeri | heavy | 500 | very heavy | 1,000 | |||

| 8/56 | Jangunte | minimal | heavy | 500 | ||||

| Sub-total: | 2,900 | 4,500 | 1,000 | |||||

| TOTAL: | 7,200 f | 9,500 | 6,730 | |||||

The command system which Umar put in place at the end of 1856 reflected the history of struggle and the priorities of the regime (see Table 5.4). The principal capital and northern stronghold was Nioro. It now surpassed Dingiray and Tamba in importance. Konyakary dominated the south-west and the critical Senegambian corridor. Three smaller posts watched over the Soninke communities while the north-east was left to the jurisdiction of Sambunne. The other principal fortifications were on the southern and south-eastern marches, where the jihadists had suffered their sharpest reverses in 1855 and 1856, and where renewed opposition, whether Bambara, Soninke, or Mandinka, might be expected to emerge.

| Village | Province | Origin in Senegambia | Date |

| Gajaba | Kingi | Fuuta-Tooro | c. 1856 |

| Gassa | Kingi | Fuuta-Tooro | c. 1855 |

| Getema | Kingi | Ɓundu and Fuuta-Tooro | c. 1855 |

| Gimbanne | Kingi | Ɓundu | c. 1856 |

| Korkojo | Kingi | Fuuta-Tooro | c. 1855 |

| Mandalla | Kingi | Fuuta-Tooro | c. 1856 |

| Missira | Kingi | Fuuta-Tooro | c. 1856 |

| Nioro Medina | Kingi | Ɓundu and Fuuta-Tooro | c. 1855 |

| Nioro Tuguni | Kingi | Wolof areas | c. 1855 |

| Samba Gore | Kingi | Fuuta-Tooro | c. 1856 |

| Yelimane | Gidiyumme | Ɓundu and Fuuta-Tooro | c. 1855 |

Table 5.4 — Umarian Garrisons in Karta in Early 1857a

| Post | Jurisdiction | Person in charge |

| Nioro | Kingi and general Karta | Alfa Umar Baila |

| Konyakary | Jombokho and routes to Senegambia | Cerno Jibi |

| Jangirde | Jangunte and southeast | Abdullay Hausa |

| Jala | Jalafara and south | Sulaiman Baba Raki |

| Tambakara | Jafunu | Jubairu Bubu |

| Niogomera | Gidiyumme | Modi Mamadu Pakao |

| Kerane | Kanyareme | Cerno Amadu |

| Farabugu | Karta-Bine and south | Cerno Khalidu |

| Gemukuruba | Gemukura and south | Umar Lamin |

Karta was the most important key to the survival of the Umarian successor states in the three decades after the jihaad 43. Unlike Dingiray, it was integrally connected to the continuing recruitment in the west and the area of conquest and occupation in the east. After a modus vivendi was established with the French in 1860, the Umarian leaders could reduce their vigil on the south-western flank and concentrate on the long lifeline of support to Segu. They maintained reasonably good relations with Moorish traders and the desert-edge economy, and used Saharan salt in exchanges for gold, kola, and slaves in the south. The sparsely populated Mandinka zones below Karta offered little threat, while the Massassi were not able to pose a new challenge for some time. This began to change in the 1880s with the French advance towards the Niger, but until that time the Umarians maintained a relatively strong and prosperous Karta secured by a belt of garrisons which bore a striking resemblance to the Massassi heartland in the early nineteenth century.

One explanation for this success lay in a certain measure of indigenous support. A more important ingredient was large scale colonization. The pattern which Umar began around Nioro in 1855-6 was enlarged, while a second area of settlement was developed around Konyakary in the southwest (see Map 2). Both areas were critical to the control of Karta and the west-east corridor. Konyakary assured the continued supply of men and material from Senegambia, while Nioro protected the north and the surest route to the Middle Niger. The settlers were primarily Fulbe from the Senegal River valley and especially from Fuuta-Tooro. Men predominated but probably not as much as in the days of the jihaad. They left because of conditions at home, often associated with increasing French domination, and in response to envoys from the east. From my preliminary findings, the largest flow of recruits corresponded to the two periods when Amadu Sheku, Umar's oldest son and principal successor, resided in Nioro and intensified the call to recruitment 44.

Map 5.2 — The Umarian colonization of Karta in the late 19th century

The first stay in the Karta capital corresponded to 1870-4 and the first major revolt within the Tal family. Habib and Moktar, sons of Umar by Mariam Muhammad Bello, used their mother's prestige and their Dingiray supporters to cut off the western part of the jihadic state 45. They took the forts of Kunjan and Konyakary without a struggle. They were on the verge of taking Nioro away from Mustafa, the Hausa servant that Umar posted there in 1859, when Amadu arrived in 1870. The oldest son needed three more years to capture his brothers and end the revolt. Part of the delay came from a second rebellion, masterminded by the Massassi remnant, who seized the occasion provided by the Umarian power struggle. The Bambara attacked the weak south-eastern flank of the state. In 1874 Amadu finally destroyed their base, drove the Massassi back into exile, and had himself officially proclaimed Commander of the Faithful in the presence of Tijaniyya leaders from West and North Africa 46. Then he returned to Segu, where he kept Habib and Moktar in prison until their deaths in the early 1880s.

The four-year campaign disrupted the economy of Karta and the fragile unity of the Umarians. A relatively peaceful and prosperous period ensued under the command of Muntaga, Amadu's brother and new appointee. Caravans and envoys again moved in all directions. But the double menace of Bambara revolt and Tal discord struck a few years later. The Massassi moved back into the south-eastern zone in 1879, this time to stay. Their salient served as a screen to Muntaga, who began to establish his own autonomy in Nioro. Both of the rebellions were encouraged by the French as part of their strategy of expansion towards the Niger 47.

To save his kingdom Amadu was obliged to return to Nioro in 1885. This time the Commander of the Faithful was not sufficiently strong to deal with both threats, and concentrated on Muntaga. Using all of the military and moral force at his command, he isolated his adversary in the palace and virtually forced him to commit suicide. By 1886 he had destroyed the other centres of revolt 48. In the four years remaining before the French conquest, he recreated some of the old prosperity of Karta. His calls for new recruits coincided with French consolidation in the Senegal River valley. Many Fulbe were threatened with a loss of slaves to French posts, and they migrated by the thousands to Nioro. There they reinforced Amadu's authority over against the more entrenched talibe and played a leading role in resistance to the French. Their action made Fergo Nioro, “emigration to Nioro”, a kind of later equivalent to participation in the original jihaad 49.

The new arrivals also assisted Amadu in achieving the closest approximation to an Islamic society produced by the Umarian enterprise 50. In this arrangement Nioro was the main capital and controlled the northern provinces directly. The south-west fell to Konyakary and the south to Jala. The tithe on agricultural and livestock production was collected systematically from the indigenous population. Qadis dispensed justice at the village and provincial level; the Nioro court was the ultimate appeal. Any property without an inheritor reverted automatically to the state. Caravans paid a tax of 5 to 10 per cent. A substantial portion of these revenues were distributed to the talibe by Amadu, who overcame some of the reputation for frugality which he had acquired in Segu. The educational system had the same pyramid as the judicial and economic: Koranic schools in most villages, and in all settler villages, formed the bottom layer, while Nioro with its more specialized scholars constituted the top. The net effect of these institutions was to encourage the spread of Islam, in breadth and depth. This occurred particularly in Jombokho and Kingi, and particularly among those most closely associated with the new settlers.

The colonists of the late nineteenth century found the same kinds of opportunities as the talibe who emigrated under Umar. Karta offered land, the opportunity to acquire a labour force of slaves, and freedom from most taxes. It provided the satisfaction of participating in a more self-consciously Islamic society and getting away from the growing French influence in the west. The social stratification of Fulbe society changed very little. Persons of modest commoner origins could now claim the dignity of talibé, and perhaps acquire a chieftaincy in a new quarter or village, but most people remained within the vertical patronage relationships by which they had come. They settled, fought, and generally identified themselves as belonging to the unit of some specific Fulbe noble. Around Konyakary and Nioro the settlers were sufficiently numerous to alter the demographic equation, dominate the administration and army, impose their language, and in general re-create a familiar life style. For these reasons they preferred Karta to what they understood as the isolated and hostile atmosphere of Segu 51.

The population of the western and northern parts of Karta at the turn of the century was probably about 150,000 52. Roughly one-third was slave. Some 40,000 lived in Jombokho, perhaps 50,000 in the Soninke Kolombine areas, and 60,000 in Kingi. If one adds in the 20,000 Senegambian Fulbe whom the French expelled in the early 1890s 53, the final total reaches 170,000. By my estimates about 40,000 of these were settlers: 10,000 lived in Jombokho, where they constituted perhaps 25 per cent of the population, and 30,000 in Kingi, where they approached 50 per cent. Even allowing for the absorption of local wives and slaves, these figures dramatically demonstrate the ability of the jihaad and state to mobilize and maintain Senegambian Fulbe migration. The history of these parts of Karta, and the phenomenon of colonization, should be a high research priority.

In the eastern and southern portions of the region the Umarians achieved much less on all fronts. The regime consisted principally of garrisons of sofas and talibe who tried to protect the trade routes and a small number of friendly villages 54. The relations with the majority were neutral if not hostile. New settlements were not established, Senegambian and Islamic institutions were not created, and the Muslim faith did not spread. The causes can be found on several sides: in the continuing Massassi and Segu Bambara resistance, the absence of strong indigenous support, the distance from Senegambia, and the failure to colonize.

Notes

1. The sending of the letters is mentioned in Umar's treatise justifying his expedition against Masina (BNP, MO, FA 5605, fos. 2-29). See chapter I, note 41.

2. See chapter 1, notes 17 and 18.

3. The best description of Karta in the mid-nineteenth century is Raffenel, Nouveau voyage, I, passim. See also Carrère and Holle, Sénégambie française; Monteil, Bambara; E. Pollet and G. Winter, La société soninké (1971), chapters 1-3; Soleillet, Voyage, pp. 194 ff.; and Tauxier, Bambara, pp. 112 ff.

4. G. Doutresoulle, L'élevage au Soudan français (1952), pp. 179-86; R. Law, The Horse in West African History (1980), pp. 29, 53-8.

5. This observation comes from a number of nineteenth-century sources. The boundary between the cloth and cowry zones apparently corresponded more or less to the buffer zone between the states of Karta and Segu. Carrère and Holle, Sénégambie française, p. 187; Mage, Voyage, p. 457; Soleillet, Voyage, pp. 99, 253-4. See also Curtin, Economic Change, 1, pp. 237, 269-70.

6. Pollet and Winter, Société, passim, especially map 2 facing p. 52. See also Curtin, Economic Change, 1, pp. 142-5. On the importance of Lake Marghi and the Kolombine system in general, see Doutressoule, L'élevage, pp. 52 ff.

7. On the Mandinka chiefdom or kafu see Person, Samori, I, pp. 64 ff. Karta in its original and restricted sense consisted of the southern provinces of Jalafara, Karta-Bine and Jangunte. E. Blanc, “Contribution à l'étude des populations et de l'histoire du Sahel soudanais”, BCEHSAOF 1924.

8. On the Jawara see E. Blanc, “Notes sur les Diawara”, BCEHSAOF 1924, and G. Boyer, Un Peuple de l'Ouest soudanais: les Diawara (1953), pp. 39-41.

9. For Massassi history and the tonjon, see Monteil, Bambara, pp. 290 ff., and Raffenel, Nouveau voyage, I, pp. 363 ff.

10. On the organization of the Massassi state, see Raffenel, Nouveau voyage I, pp. 189 ff., 244 ff., 323 ff., and 435 ff.

11. On religious practice, see Monteil, Bambara, pp. 119 ff., and Raffenel, Nouveau voyage, I pp. 236-9, 311, 318-22, 395 ff.

12. Most of the expansion of Karta was carried out by Musakoroba (c. 1795-1808) and Bojan Moriba (c. 1815-32). Tauxier, Bambara, pp. 125 ff., On the Jawara troubles, see Raffenel, op. cit., pp. 244 ff., 299-300, and 325 ff.

13. Raffenel was forced to turn back as he approached Jangunte, the westernmost province under Segovian control. He then spent several months in the Massassi garrison town of Futobi as a virtual prisoner until his departure in December 1847. Raffenel, op. cit., pp. 296 ff., 311-13, 463. For his estimate of Mamadi Kanja, see page 236.

14. Raffenel, Nouveau voyage, I, p. 436 (see also pp. 405-6, and chapter 4, note 8). Mage ( Voyage, p. 63) thought that Karta was a weak state on the eve of the jihaad.

15. ANS 13G 167, pièce 15 (19 Aug. 1855, Commandant Bakel to Governor); interview with Demba Sadio Diallo cited in chapter 4, note 59. Segu 3/Cam, p. 78; Tauxier, Bambara, p. 154. All of the internal narratives treat the Karta campaign in some detail, but the richest are BNP, MO, FA 5559, fos. 1-6; Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali; Segu 3/Cam; Nioro 2/Adam Nioro 3/Delafosse; and Segu 2/anonymous. The last three are very similar to one another.

16. Segu 3/Cam, p. 62; Pollet and Winter, Société, pp. 44-5, 69. The Soninke of Jafunu quickly embraced the jihaad, Gidiyumme was more cautious, probably because of the stronger Massassi presence there.

17. For the Kulibali lineages see Monteil, Bambara, pp. 118, 214; Raffenel, Nouveau voyage, I, pp. 380-1; Tauxier, Bambara, pp. 112 ff. The Umarians none the less needed inside information and special tactics, such as the wooden ladders for scaling walls which their Jafunu supporters constructed, to overcome the defences of Yelimane and Medina. Pollet and Winter Société, p. 69. See also Blanc, “Contribution”, pp. 274-5.

18. On Wulibo see Nioro 2/Adam, p. 736; Nioro 3/Delafosse, p. 360; BNP, MO, FA 5693, fos. 16-17; 5713, fos. 23, 60.

19. Segu 2/anonymous. The description is very close to that provided by Faidherbe's informants (ANF, OM SEN I 41b, 27 July 1855, Governor to MMC). In Tagno Umar had received the submission of a Sirabalen Massassi who was also a Muslim cleric. Nioro 2/Adam, Nioro 3/Delafosse.

20. Muhammad destroyed some of the objects of the temple on his return to Mecca in AD 630. Umar was probably conscious of imitating this hallowed precedent, and his chroniclers certainly had it in mind. This scene is stressed in the earliest accounts (BNP, MO, FA 5559 and 5732 and Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali, where the objects are called asnam).

11. See chapter 4, notes 2-5. See also BNP, MO, FA 5732, v. 70.

22. BNP, MO FA 5559 fos. 1-6, Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali, p. 255. In Nioro 2/Adam, pp. 737-8, one battalion is called Bossea rather than Yirlaaɓe. On Umarian military organization and its changes see Segu 3/Cam., pp. 138, 148-9, 153, 159-61; Delafosse, Haut-Sénégal-Niger, II, p. 320; and Mage, Voyage, pp. 174, 293.

23. Many of the men from Fuuta-Jalon were performing garrison duty in Dingiray, Tamba, and other installations.

24. The original meaning is probably “the meeting of slaves”, jon-futu (Monteil, Bambara, p. 191). By extension it came to mean a palace guard or a turret for defence. Dingiray/Reichardt, pp. 250-7; Segu 3/Cam, pp. 147, 153; Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali, p. 255; Reichardt, Vocabulary, p. 344.

25. By the summer of 1855, Umarian recruiters were taking newly enslaved persons with them to Senegambia to show the fruits of jihaad. ANF, OM SEN 1 41B (27 July 1855, Faidherbe to MMC); ANS 3B 77, pièce 12 (15 Dec. 1856, Faidherbe to Commandant Podor).

26. Political leaders often preferred slaves to free men because of their greater loyalty. See Peter Lloyd, “The political structure of African kingdoms: an exploratory model” (in M. Banton, ed., Political Systems and the Distribution of Power, 1965), pp. 78 ff.

27. Segu 3/Cam, p. 57.

28. Segu 2/anonymous. The accounts in the Nioro sources, Bandiagara/ Abdullay Ali, Segu 3/Cam and BNP, MO, FA 5732 are almost identical, suggesting a common miracle corpus which is no longer extant. See chapter I, section B.

29. Gunjuru was an old Soninke and Jakhanke commercial and clerical centre. Umar began using it for liaison with Tamba early in 1855 if not before. Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali, pp. 9-10, Monteil, “Le site de Goundiourou”, BCEHSAOF, 1928; chapter 3, note 91.

30. For the meaning of tuburu see Mage, Voyage, pp. 228-9, 290-3, and Soleillet, Voyage, pp. 367-8.

31. Segu 2/anonymous. On the Massassi and their wives see Raffenel, Nouveau voyage, I, pp. 380-1. On Mamadi Kanja's accumulation, see ANF, OM SEN I 41b (27 July 1855, Faidherbe to MMC).

32. Segu 3/Cam, p. 68. On the revolt in general see the internal narratives cited in note 15 and Carrère, “Siège”, passim.

33. Mage, Voyage, p. 153. See Blanc, “Contribution”, pp. 274-87, for the Massassi villages destroyed in 1855.

34. On Samba Njay Bacily and his critical role in construction and artillery, see Mage, Voyage, pp. 132, 153, 169; Soleillet, Voyage, pp. 325-7; Y. Saint-Martin, “L'artillerie d'EI Hadj Omar et d'Ahmadou”, BIFAN, B, 1965.

35. On the Jawara revolt, in addition to the internal narratives cited in note 15, see ANS 15G 108, pièce 25 (17 Dec. 1855, Commandant Holle to Governor); ANM ID 51, pièce 7 (1954 report on the Jawara); Segu 3/Cam, p. 84; Blanc, “Notes”, pp. 93-6; and Boyer, Diawara, pp. 43-7.

36. On Masina and its role in eastern Karta or Bakhunu, see Bâ and Daget, Empire peul, pp. 173 ff.; Raffenel, I Nouveau voyage, pp. 132, 137, 430, 493. The Umarian version of the conflict is given in BNP, MO, FA 5605, fos. 2-29, and 5684. fos. 138-42. The Masina version can be found in 5681, fos. 6-12; Ma Jaara; Diarah, “Maasina”, pp. 354-62; ANS IG 122, “Notes sur l'histoire du Masina” (Capt. Underberg, I Mar. 1892).

37. The only direct evidence linking the Masina army and the Jawara revolt concerns the battle of Jongoji in June, after Jabige and before Bassaka, and it comes from Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali, p. 7.

38. Blanc, “Notes”, pp. 95-6. See also ANM ID 51, pièce 7 (1954 report on the Jawara). Alfa Umar Jakhite protested within the Umarian ranks but was not heeded. This incident may have started his disaffection from the Futanke talibé ranks. 39. The Kassakeri battle may have lasted as long as three days. Nioro 2/Adam, p. 742. For Kassakeri's location and role as capital of northern Bakunu, see Lartigue, “Notice géographique sur la région du Sahel”, BCAF/RC 1898, p. 124.

40. For Umar's delegation to Segu, see Mage, Voyage, pp. 143, 154-5. See also note 13, above.

41. From Archinard's archives and found in Jacques Méniaud, Les Pionniers du Soudan, Il, pp. 332-3. Nuhu was governor of Jafunu at the time. Dama, Mari Sire's brother, was one of the refugees welcomed at Bakel in 1855. See ANS 13G 167, pièce 17 (13 Oct. 1855, Commandant Bakel to Governor). See also Méniaud, Pionniers, I, p. 156, and II, pp. 330-8; Monteil, Bambara, p. 117; Tauxier, Bambara, pp. 157-8.

42.

43. The most useful archival sources on Karta in the late nineteenth century are contained in ANM ID 51; piece 2, “Notice historique sur le Sahel”, by Commandant Lartigue, was also published in BCAF/RC 8 (1898), pp. 69-101, along with his “Notice géographique sur la région du Sahel” (ibid. pp. 109-35). See also Mage, Voyage, pp. 403-6; Marty, Soudan, IV, pp. 204-6, 238-54, 261, 272-8; Piétri, Les Français au Niger (1885), pp. 226 ff.; Soleillet, Voyage, pp. 367 ff., 479 ff. Docteur L. Colin (“Le Soudan occidental”, RMC 1883, pp. 5-32) gives a picture of a prosperous commercial economy in Karta in about 1882.

44. See Robinson, Chiefs and Clerics, pp. 51, 59, 67, 73, 82-3, 86, 91, 102, 112-13, 191-2.

45. See Oloruntimehin, Empire, pp. 178-94. Oloruntimehin's account is very confused, but it does make use of the main sources in Piétri, Soleillet, and the archives of Medine (ANS 15G 109).

46. For a corpus of letters and statements celebrating Amadu's triumph over the Bambara and his proclamation as Commander of the Faithful, see BNP, MO, FA 5640. See also Piétri, Français, pp. 102-10, and Soleillet, Voyage, pp. 365-80. Amadu may have begun using a seal, which proclaimed him Commander of the Faithful, in 1868. BNP, MO, FA 5713, fo. 59.

47. The main sources can be found once again in Oloruntimehin, Empire, pp. 225 ff.

48. Particularly Lambedu in the south. Four brothers of Muntaga, including Amidu and Muniru who survived, and Daye and Daha who did not, were involved in the revolt.

49. Robinson, Chiefs and Clerics, pp. 49-51, 127-8, 136-7, 142-9. Amadu did have to contend with the very substantial revolt of the Soninke of the Kolombine valley in 1886-7 in support of the Soninke cleric Mamadu Lamin Drame. See Blanc, “Contribution”, pp. 305-14; Monteil, Khassonkés, pp. 369 ff.; Pollet and Winter, La Société Soninke, pp. 69 ff.

50. ANM ID 51, pièce 2 (Lartigue, “Historique”); Galliéni, Deux campagnes, p. 34; Méniaud, Pionniers, vol. 2, pp. 60-1.

51. Blanc, “Contribution”, p. 275; Galliéni, 1879-81 p. 592; Piétri, Français, p. 251; Y. Saint-Martin, Relations, p. 144; Soleillet, Voyage, pp. 376-8.

52. I have used ANM ID 51, pièce 4 (1899 census figures compiled by Lanrezac) and 5D 29 (a 1904 census for Khasso, with figures for portions of Jombokho).

53. For details on the expulsions of 1891 and 1893, see Méniaud, Pionniers, vol. 1, p. 513, and vol. 2, pp. 336 ff.

54. The strongest Umarian garrison in eastern Karta in the late nineteenth century was Wossebugu, under Banjugu, a Massassi who joined the jihaad. See note 42 above.