Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1985. 420 pages

Many pre-colonial histories of the West African savanna begin with a description of Arabic, European, and oral sources. The Arabic materials correspond to the perspective of the literate local alive. They require the traditional skills of the Islamicist. The European sources consist of travellers' accounts and archives from local posts. They demand the talents of the archival historian. The oral materials, consisting of more formal traditions and less formal recollections, require the skills of collection and analysis of the field-worker. In most cases they have been tapped as a supplement to the first two categories.

The evidence for the study of the Umarian movement seems to fit this division very well. But here I wish to insist upon an analysis of evidence which stresses the conditions under which it was created and transmitted. In the middle and late nineteenth century partisans and opponents of the jihaad formulated their impressions in a world of competing Islamic causes, growing violence and increasingly decisive European intrusion. Some of these formulations were quickly written down. Some were transmitted orally for several generations, while others have survived primarily as oral traditions until the present day. By looking carefully at the processes of formulation, transmission, recording, and use of the accounts, the historian can gain important new insight about the events, relationships, and impact of the jihaad .

The place to begin an analysis is with the Fulɓe, Mandinka, Soninke, and other societies of the nineteenth-century Western Sudan where the jihaad was played out. In the terms employed by Jack Goody, these societies possessed specialized and restricted literacy in Arabic 1. It was specialized in the sense of being controlled by a relatively small élite of clerics, and restricted in the sense that it was used for a limited range of subjects. All of the people, including the clerics, used a local spoken language for most purposes most of the time. Over a considerable period of time the spoken and written languages had developed complementary relations with each other.

The responsibility for transmitting historical data by written and oral means was clearly delineated in these highly stratified and relatively centralized societies. Across the social structure five distinct categories of person can be identified.

Slaves formed a very large group in the nineteenth century. Although some of them enjoyed considerable influence as soldiers or bureaucrats, all shared in the kinlessness and ultimate powerlessness which defined their condition. Rarely did they receive an education beyond the apprenticeship of work; rarely did they become the objects or bearers of history. Only with assimilation to the lineage of the master did slaves acquire status in the society, and that process usually required several generations 2.

A second category consisted of endogamous groups, often called castes in the literature, who performed critical services for the society or state. Most of them possessed skills in fashioning iron, wood, cloth, pottery, and other essentials of the material life. Others fulfilled the function of « Griot », a West African term connoting the roles of historian, minstrel, and courtier 3.

The griot was responsible for attending to the needs of his patron, be he a village chief or a great king. To the accompaniment of musical instruments, he recited genealogies, recounted the exploits of past heroes and generally entertained the court. By virtue of his inferior and hereditary status and his intimate knowledge of the society, he often arbitrated in disputes between lineages, mediated between families to arrange marriages, and served his patron as counsellor and ambassador. Anne Raffenel, a Frenchman who travelled widely in the Upper Senegal in the 1840s, had this to say about the social position of some of the leading traditionalists of the Khasso kingdom:

Khasso has the distinction of furnishing male and female griot for the Mandinka chiefs, especially the Bambara. The griots of which Sanimussa [a Mandinka chief of the Upper Faleme valley] was so proud came from Khasso.... The role [of griot] is not such a bad one. The griots are very important to their masters. They are treated handsomely and live in luxury, for fear that they will find another patron. Fully confident, their fickleness is equalled only by their greed. They lead a privileged existence and know how to take advantage of it. Whoever wants to see the master must first purchase the griot's favour. It's the griot who handles marriage negotiations and who is rewarded when they succeed 4.

The story recounted in Chapter 3 about Jeli Musa, griot and ambassador of the Mandinka king of Tamba at the outbreak of the jihaad, is another illustration of the social and political importance of these traditionalists in the Western Sudan.

The training of the griot followed the pattern described by Milman Parry and Albert Lord for the Southern Yugoslavian bards 5. The apprentice listened to the recitations of accomplished performers, learned the formulas and themes, and eventually gave his own versions. He steadily acquired a repertory of stories, genealogies and dynastic narratives and developed an ability to select his material in relation to the composition of each audience. As his reputation grew he might journey to other regions and learn other collections of traditions. In contrast to the Yugoslavian model, the griot inherited his profession, learned to perform from members of his own family at an early age, and earned his living from the gifts of his patrons. His repertory included a large number of fixed texts, such as genealogies.

Above the slaves and endogamous groups lay several categories of free persons. In addition to simple farmers and herders, this stratum included the ruling lineages, who were the patrons of the griots, and the Muslim traders and clerics, who were the custodians of literacy in Arabic. Clerical education, in its emphasis on apprenticeship and memorization of fixed texts, resembled the training of the griot. Between the ages of five and ten the pupil began Koranic school, usually in his own village and in the company of his male contemporaries. After learning to read and recite the Koran, the more able pupil left his peers behind and attached himself to teachers who specialized in particular treatises on the Arabic language, Islamic law, and theology. This made it necessary to travel from school to school; at each stop the student performed domestic and agricultural chores for his master and laid the foundations for a personal library by copying the master's manuscripts. In time the student became a teacher, establishing his own reputation for knowledge of a particular work or branch of Islamic learning 6. He might also accede to the position of local judge (qaadi), leader of worship (imam) or accountant and broker in the market place. The peripatetic pattern emerges in a chronicle about a very distinguished cleric in the early 1800s:

Karamokoba was taught by his father, Muhammad Fatim. When his father died he went to Kinta in the land of Yani and studied Koranic commentary under Shaikh Uthman Dari. Then he returned to Didi. Then he went to Gurjuru where he read the Mukhtasar of Shaikh Khalil under Shaikh Ibrahim Jani ... Then he left there and went to Junbughu and read grammar and conjugation under Fodi Umar Ture... 7

Karamokoba became the founder of the famous Jakhanke school of Tuba in Futa Jalon.

While the level of Islamic education was often mediocre, most clerics could read simple texts and correspond in Arabic. Some became accomplished poets, grammarians, theologians, and legal experts. These more proficient scholars might also write chronicles (ta'rikh). The art of writing chronicle was rarely taught and rarely formed the basis of a cleric's reputation. Because of this lack of emphasis and by virtue of the close ties between the clerical and ruling classes, most of the traditional historical literature of the Western Sudan consists of dates, genealogies of chiefs and scholars, events associated with their careers, and accounts of major battles. It is replete with stereotypes of reformers who refuse to visit the courts of kings, or tyrants who rip babies from the wombs of their mothers. Rarely did the scholars probe the problems of causation, motivation, and bias, or present the perspective of the subordinate classes 8.

The Islamic revolutions brought some significant changes to the social structure and educational patterns in Fulɓe societies. The gap between cleric and chief was diminished, since the new ideology called for the learned man to rule. In practice, the new leaders often had only rudimentary Muslim education, but they were often responsive to the indications of the law and the interventions of the scholars. A higher proportion of the children of the free classes attended Koranic school and a somewhat larger number undertook clerical careers. More teachers could be maintained because of the ideological commitment to Islamic learning and the increased supply of slave labour for basic productive tasks. Hyacinte Hecquard, French explorer in the Upper Senegal in the mid-nineteenth century, has left impressions of village education in the Fulɓe state of Futa Jalon:

[In Futa-Jalon] each village has several public schools. The wealthy entrust their children to a well-known marabout [cleric] who takes responsibility for their education until they know the Koran.... When the pupils have read the Koran, they learn to write Arabic. All of the free Fulɓe know how to read and write, but it is expressly forbidden to give instruction to slaves 9.

In Ɓundu he found a similar pattern:

Islam is the only religion in Ɓundu. No non-Muslim can reside there except under the protection of one of our commercial posts. As among blacks in general, the inhabitants of this country emphasize doctrine less than worship, whose rituals are scrupulously observed. There is virtually no village where they do not maintain schools where the children learn to read and write 10.

As I will show in Chapter 2, Fulɓe scholars in Futa Jalon devised equivalences between Fulfulde sounds and Arabic letters and used this alphabetic system to create a Fulfulde vernacular literature 11. It was designed for pedagogical purposes, and specifically for recitation to those who could not understand Arabic, but it could also be used for writing historical narrative, in prose or poetry, as the Umarian chronicles demonstrate.

The griots and scholars did not live in isolated compartments. Griots listened to the translations of Arabic documents and the recitation of Fulfulde material. Clerics attended performances based on the continuing oral tradition. Both groups mingled at the court. Both reflected the views of the ruling classes. The Islamic movements increased the cross-fertilization and even mixed the traditional social categories. Some griots learned to read, write and recite Arabic and began to use chronicles in their sessions. This did not necessarily diminish their ability to improvise in their mother tongue, as Lord maintains 12. Commoners with rudimentary Koranic instruction learned Arabic and Fulfulde transcription and wrote about the jihaad. Many people heard the accounts of griots, clerics, and disciples, recalled their own experiences and transmitted the blend of traditions orally to their descendants. The colonial situation has increased the process of mixing genre and content even more.

The extensive interaction among classes and among the various forms of composition and transmission argues against the conventional distinctions between written and oral sources. It is much more instructive to treat each source as a document which involves original testimony, transmission and a time of recording in writing or on tape. The historian can then search for the affiliations of witnesses, transmitters, and compilers to determine bias, purpose, omission, emphasis, and general reliability 13. Even the ostensibly contemporary French reference involves transmission from observer through informants to an explorer or post commander. Consequently I have chosen to divide materials according to commitment: whether they stand basically inside or outside of the Umarian tradition. Subsequently I consider the context of the document: in what ways has it been shaped by intention, ideology, and public performance?14 The Masina material, miracle literature and some other fragments constitute a mixed rubric. The French sources become part of the external category.

Membership in the Umarian community and participation in the jihaad decisively transformed the lives of many Senegambians and Guineans in the mid-nineteenth century. The vast majority were Fulɓe, descendants of the pastoralists who had migrated throughout the Western and Central Sudan and prized loyalty to clan and cattle more than attachment to land 15. They belonged to the societies of Futa Jalon, Ɓundu, and Futa Toro where recent Islamic movements had altered the basis of government and education. Now they responded to Umar Tal, the pilgrim who spoke to their Fulɓe consciousness, evoked their sense of Islamic obligation, and called them to jihaad against the « pagan » Mandinka and Bambara. Should they die fighting they would go immediately to Paradise. Should they defeat the enemy they would enjoy the material and spiritual benefits of a new Muslim society which would surpass the achievements of the earlier revolutions. What began as a commitment of months became a new way of life. The talibe, the « disciples » and soldiers of the new movement, joined the Tijaniyya, the new order which Umar propagated. They fought against notorious warriors and watched many of their own die. They reigned over strange lands and people whom they did not understand and could barely control. Their success and their predicament intensified their consciousness as a chosen people.

During the years of fighting, the jihadists generated very little writing. Umar maintained some correspondence 16. He did encourage talibe to write accounts of the early and middle periods of the jihaad. One poem, composed in Fulfulde by a man from Futa Toro, deals briefly with the campaigns between 1852 and 1855. The author probably intended his work for recitation to the faithful to remind them of their achievements and ultimately the achievement and inspiration of Umar. Fully 40 per cent of the 130 verses are devoted to praise of the leader 17. The second piece is an Arabic chronicle, in poetry and of unknown authorship. It carries the story of the jihaad a bit further, through the battles of 1856, and with much greater detail. It contains very specific dates of battles and occasional references to casualties and climatic conditions 18. Both chroniclers were eyewitnesses of much of what they describe. They almost certainly wrote before the great loss to the French at Medine in 1857. They reflect the mood of 1856, when Umar had achieved domination of Karta, was hesitating about confrontation with the French, and had not yet decided when to extend his jihaad against Segu. Another important document written during the war years is the « chronicle of succession » of Amadu Sheku which occurred near Segu in February 1860. Written by a Futa Jalon scholar who had helped educate Umar's sons at Dingiray, this account shows Umar entrusting major political responsibility to Amadu 19. Other documents give important details of the Masina campaign 20. All of these documents were available to the authors of the chronicles produced after the jihaad.

Some documents no longer extant undoubtedly existed at the time of the jihaad. The most obvious was a register, or at least one register of dates of battles, names of leaders, numbers of soldiers, and figures of casualties and booty. The attention to booty probably reflects the public accounting after each victory in which the state's conventional 1/5 share was determined 21. Someone in the main Umarian camp kept such a document. It was subsequently copied for use in the various capitals and used in the compilation of the later chronicle 22. An account of the specifically Kartan phase of the jihaad probably also existed, to judge by the existence of virtually identical narratives in several chronicles 23. It may have been an elaboration of the Fulfulde and Arabic chronicles of the early jihaad.

The death of Umar in 1864 ended the jihaad, except for defensive struggles in separate theatres, and dealt the disciples a fearful blow. The one person who could evoke their commitment and give meaning to their actions had disappeared, leaving a sprawling expanse of scarcely conquered territory and a host of inexperienced sons and nephews. It was crucial to consolidate the jihaad and tell its story, but the Tal and talibe faced the task of formulating a unified tradition from a particularly awkward posture. A large concentration of the elect lived at Segu around the court of Amadu, the oldest son with the best claims to succession. Some of the earliest disciples together with most of the wives and younger children of Umar still resided at Dingiray, the first capital at the edge of Futa Jalon. Many recruits from Ɓundu and Futa Toro could be found at Nioro, the second capital and staging area for the conquest of Segu. Finally, a small group of the faithful, who acquired new prestige by leading the reconquest of Masina in the mid-1860s and 1870s, gravitated around the court of Tijani, Umar's nephew, at Bandiagara. Given the distance between these centres, the conflicts among the Tal and talibe, and the continual revolts of the subjects, it was inevitable that the internal accounts of the jihaad would develop without any overall co-ordination.

Writing the story was not a quick or automatic process.

Who had been close to Umar? Who could tell all? How could an account be corrected? For whom was it destined? Whose position would it enhance? One problem which the Umarians faced was a preference for oral transmission. As in the early Christian church and the early Muslim community, 24 the disciples had no need of written documents in order to relive the events of the jihaad. They preferred oral recitation as a more pure, spontaneous, and democratic way of rendering their experience. Only as they felt the need to communicate beyond the circle of participants did complete chronicles emerge. A second problem was the absence of training. Umar had written very little history. Most of his sons and relatives were too young, too poorly educated or too preoccupied. The majority of the talibe had more talent on the battlefield than in putting pen to paper. The ultimate barrier was authority: in the wake of the founder's death, who could commission an account of the jihaad and gain its acceptance in the wider Umarian and Muslim communities? Amadu delayed the process of reckoning by attempting to conceal the news of his father's death, and he did not regularly use the title of Commander of the Faithful until 1874 25. It was the rivalry between Amadu and his relatives which finally forced the Umarians to produce their versions.

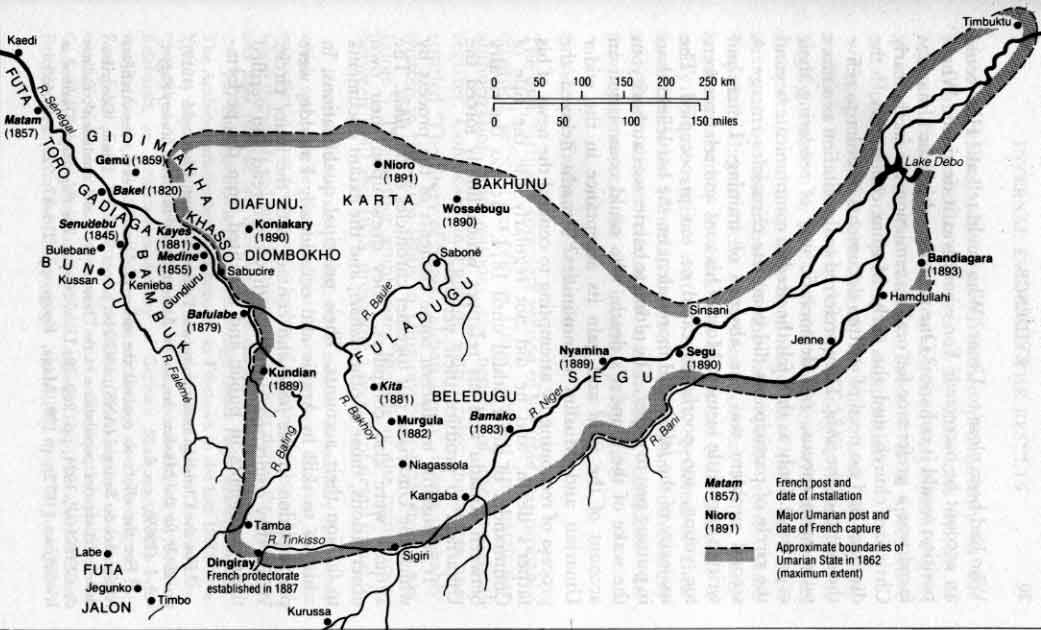

It is possible to discern some elements of the process by which the Umarians put together chronicles of the jihaad. The authors were also compilers. They drew upon their own observations, those of other talibe, and the extant documents to fashion their accounts. Their principal qualifications, in addition to skill in Arabic and occasionally Fulfulde, were participation in the jihaad and contact with the inner circle. While they composed in private, they often read and verified their statements in public and benefited from the performances of griots, who figured rather prominently in the Umarian capitals. In the cases of the chronicles written at Segu and Bandiagara, the courts exercised a significant degree of influence over the content. Table I is a speculative reconstruction of the process of composition.

The process of formulating, blending, and editing the traditions and committing them to writing as chronicles was largely complete by 1900 26. Some traditions were not written down at all and may have been forgotten. Others have been recorded by researchers in the last twenty years. More frequently the chronicles have been recopied, recited, translated, and thereby fed back into the extant oral traditions of today. These earlier written accounts, because of their formation in the Umarian foyers of the late nineteenth century and their shorter chains of transmission, constitute the privileged sources for the internal perspective.

The first, virtually complete version of the jihaad was probably recorded before the death of Umar, without any particular authorization and without the benefit of the statistical register. Composed in Fulfulde with Arabic characters and entitled « The Story of Shaikh al-haj Umar », it was probably written in the early 1860s in Dingiray by a talibe from Futa Jalon 27. The author emphasizes the life of the community between 1840 and 1853, providing a wealth of detail found in no other source. Particularly precious are his immediate, spontaneous glimpses of Umar. After 1853 the account becomes condensed, hesitant, and derivative 28. It scarcely mentions the Karta campaigns, confuses the battles for the Segu kingdom, and omits any description of the Masina phase. The author, like many of the disciples from Futa Jalon, did not join in the later jihaad and relied on second-hand testimony. I call this chronicle Dingiray/Reichardt.

The second account in order of composition was actually compiled by a Frenchman. Eugene Mage spent two years (1864-6) in Segu as the official envoy of the French Government to the Umarian state. Soon after his arrival he composed a synthesis of the testimony of the local talibe which occupies about forty pages in the account of his voyage 29. The explorer explained his method and results as follows:

Expecting at that time to spend only a short period in Segu, I hurried to collect the history of Al-hajj [the pilgrim] from the words of the Talibés. The first narrative which I obtained from Samba Njay (a Soninke disciple from near Bakel], our host, was quite incomplete. Subsequently, by conversation as well as questions, I amassed a number of facts which I integrated with the original narrative and used as a corrective. I do not claim to present this recital as the history of Al-hajj Umar for I know how much, especially in the wars against us, the truth is often twisted. But I do give it as the life of Al-hajj as it is told at Segu and will be told to future generations. The details may be new but the basic story will be the same, conforming to the orientation which Al-hajj wanted to give it 30.

Mage spoke no Fulfulde and not very good Wolof. He was forced to rely on the translation of his interpreters or the few talibe — such as Samba Njay — who spoke French. He none the less essentially succeeded in his endeavour to provide the version of the jihaad current in Amadu's capital in 1864. The explorer sought the best available information for his superiors, who were interested in developing commercial relations after a period of tension and hostility, and he avoided existing French stereotypes of events and relationships. The young Amadu was in no position to impose censorship on the information available to Mage. He deferred to the older and more experienced disciples for the story of the jihaad and was preoccupied with suppressing revolts. In summary, Mage gives a complete and indispensable account, much more valuable than the largely derivative narrative put together by Paul Soleillet during a later visit to the same City 31. I designate this version Segu I/Mage.

Table 1.1. Hypothetical Reconstruction of the Internal Chronicles.

The next chronicle came from Bandiagara under the title, « The Recollection of the Beginning of the Jihaad of our Shaikh » 32. This Arabic account ends in about 1880 with the re-establishment of Umarian control over much of Masina. The author and compiler, a talibe and secretary to Umar named Abdullay Ali, became an important adviser and commander under Tijani. He wrote at the behest of his patron and accurately reflected his perspective. In the place of Amadu's inheritance of the Umarian mantle, he offered the succession of Tijani; instead of the emphasis on Segu, he elaborated on the reconquest of Masina.

The Bandiagara version is essentially military history. It is particularly useful precisely because it does not attempt to give a theological justification for the jihaad or the harsh treatment of the « pagans ». In contrast to all of the other accounts, Bandiagara omits Umar's early career and pilgrimage and begins with the campaigns of 1852, when the author joined the community. Abdullay Ali does endeavour to present a complete narrative, drawing on the testimony of other disciples for campaigns in which he did not participate. He obviously had access to the register of dates and casualties in battle, for which he is the most consistent source. I call his account Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali.

An anonymous chronicle was composed in Segu in the period between the early 1870s and early 1880s 33 under the title, « The manner in which our Shaikh conducted his pilgrimage and jihaad from beginning to end. » 34 The author praises Umar's learning and power to perform miracles, stresses the cohesion of the talibe and their loyalty to their leader, and deplores the ignorance and treachery of their opponents. Amadu's succession is made quite explicit, while campaigns in which Umar did not participate are omitted. The chronicle generally reflects the perspective of Segu, and it is often accompanied by an account of Amadu's emigration to the east in the 1890s. It runs parallel to the Nioro chronicles, mentioned below, in its treatment of the Karta campaign, suggesting access to this no longer extant account. It is the most widely distributed narrative in contemporary Senegal and Mali 35. I call this version Segu 2/anonymous.

The most carefully crafted narrative is a long poem composed in Segu in the 1870s and 1880s by Mamadu Ali Thiam 36. Written in Arabic form, metre, and characters but with Fulfulde words, it was designed to reach an essentially unlettered audience through recitation. Thiam used the Fulfulde chronicle of the early and middle jihaad and the statistical register. He wrote and read his work at the court and then revised in the light of comment and criticism, taking perhaps twenty years to complete the whole. The result is a highly refined and concentrated statement dedicated to the perspective of Amadu, and appropriately labelled Segu 3/Thiam 37.

Mamadu Ali hailed from the western part of Futa Toro, not far from Umar's birthplace. He responded to his master's preaching in 1846 and participated in most of the major campaigns. He was the faithful soldier who never achieved much prominence in the jihaad or the life of the Segu court. His manuscript is marked by a number of themes which do not appear in other accounts. Umar receives the authorization for jihaad while on the pilgrimage. He patterns his actions in the years immediately before the jihaad on the model of the Prophet. On four separate occasions he installs Amadu as his successor. Throughout the narrative, Mamadu Ali stresses Umar's authority as pilgrim, khalifa of the Tijaniyya and worker of miracles, and he relishes the joys and sacrifices of the talibe. He gives exact dates for the major battles and details on the process of recruiting. By contrasting his carefully honed version with the less censored notes of Mage, the historian can discern major controversies and the innovations which Amadu introduced into the Umarian tradition.

At the turn of the century three Arabic manuscripts based primarily on oral testimony were written in Nioro with the encouragement of French colonial officials 38. None of the original versions has survived nor are the informants identified. The principal author and compiler of all three works was Mamadu Aissa Jakhite, an important judicial authority under French rule and the grandson of a prominent Soninke disciple of Umar. Mamadu Aissa collected and recorded accounts beginning with legendary events and concluding with the reign of Amadu. He made use of the Karta chronicle which is no longer extant. He drew much of his perspective from his own family, which came into sharp conflict with the Fulɓe talibe and the sons of Umar who sought to separate Nioro from the control of Segu. This explains his emphasis on Amadu's succession and perhaps the harsh depiction of talibe conduct in the conquest of the Upper Senegal and Karta. The pilgrimage receives a very brief treatment and the jihaad is rarely justified in theological terms. Unfortunately, the most detailed and interesting translation also contains substantial editorializing; in the absence of the original text, it is impossible to determine the extent of transformation 39. These narratives will be called Nioro I/Labouret, Nioro 2/Adam, and Nioro 3/Delafosse.

Another internal perspective on the Umarian jihaad emerged in Bandiagara at the turn of the century under the aegis of the only member of the Tal family who found favour with the French and approximated the position of the Northern Nigerian élite under British rule. Agibu, a son of Umar by his prestigious Bornu wife, survived the Masina revolt and the internecine struggles which ensued after Umar's death. He received the command of the post of Dingiray from Amadu Sheku.

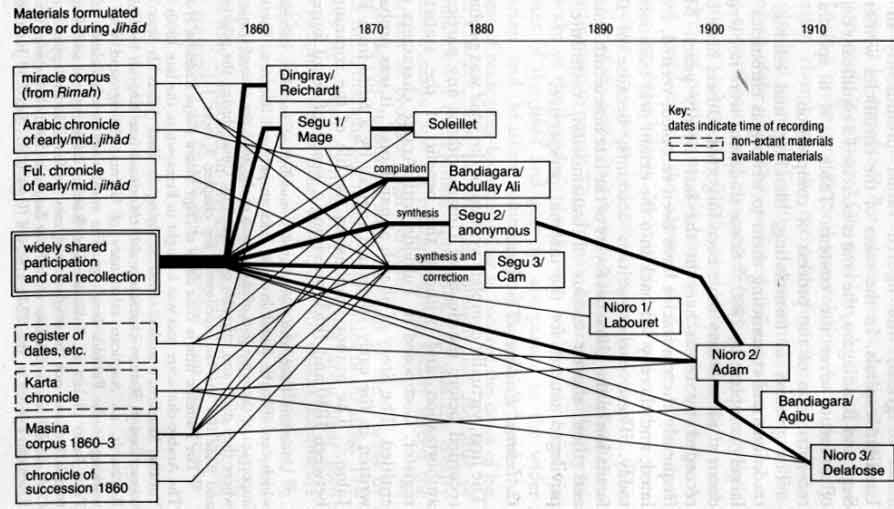

Table 1.2

The Internal Chronicles, in Probable Order of Composition

| Place & designation | Author/ compiler | Language of composition | Approximate Date | Patron | Comment |

| Dingiray/Reichardt | unknown | Fulfulde in Arabic | early 1860s | none | original? MS. not available; detailed for 1840-53 |

| Segu I/Mage | Mage | French | 1864 | none | written from testimony of talibe and griots; complete |

| Bandiagara/ Abdullay Ali Color | Abdullay Ali | Arabic | 1870-early 1880s | Tijani | written by ex-secretary of Umar, at behest of Tijani; complete and detailed |

| Segu 2/ anonymous | unknown | Arabic | 1870-84? | Influence Amadu | written by talibe; favourable to Amadu; complete but condensed |

| Segu 3/Cam | Mamadu/Ali Cam | Fulfulde in Arabic | 1870-90? | Amadu Sheku | written by talibe at Segu court; complete and carefully crafted |

| Nioro I/Labouret | Mamadu Aissa Jakhite | Arabic | 1890-1 | none | original MS. not available; compiled by descendant of talibe, very episodic |

| Nioro 2/Adam | same | same | 1900-1 | none | none original MS. not available; compiled by descendant of talibe, complete and detailed; editorialized |

| Nioro 3/Delafosse | same | same | 1910-11 | none | original MS. not available; compiled by descendant of talibe, complete |

| Bandiagara/Agibu | Agibu and entourage | French | 1908 ff | Aguibu | Agibu fragments of oral tradition relayed by Agibu and heirs to French |

In the late 1880s he began negotiations with the French, a process which culminated in his participation in Archinard's campaigns and appointment as colonial chief over portions of Masina. Bandiagara, formerly Tijani's capital, became and has remained his family's fief. By conscious decision his descendants attended French schools and acquired positions of influence within the colonial administration which have carried over into present-day Mali. The « Agibians » did not produce any complete chronicle of the jihaad, but they have had a great impact on the interpretation of it, the reign of Amadu and the French conquest 40. In particular, they have asserted that Amadu was the son of a slave woman, and by implication unfit for rule; that Agibu was the favourite son; and that Agibu was named by Umar to succeed Amadu. The historian must examine such claims critically and in the light of the family's desire to justify its alliance with the French. I designate these fragmentary accounts collectively as Bandiagara/Agibu.

After the Umarian forces moved against the kingdom of Segu in 1859 they came into sharp conflict with the Caliphate of Hamdullahi. Both sides were Fulɓe, both were the products of Muslim revolutions, both saw themselves as the vanguard of Islam in the Western Sudan. The conflict and the campaign which the Umarians launched in 1862 generated a voluminous correspondence and several treatises of justification and explanation. All of the material was written in Arabic, consonant with the scholarly audience for which it was destined, and came from three main sources:

Umar, in addition to his letters to Amadu III, wrote a tract justifying his cause 41. A few years later a Masina scholar wrote a much less polemical version of events up through the deaths of Amadu III and Umar 42. Ahmad al-Bekkay encouraged opposition to Umar and wrote to Amadu III, the Masina people in general, King Ali of Segu, and Umar 43. The controversy over the Masina campaign has not been resolved and sustains a lively body of oral tradition today 44. Although this phase of the jihaad is obviously well documented, the very intensity of the debate often obscures the events, sequence and the most appropriate interpretation.

A significant number of miracle stories appear in the sources. Some emerge in particular contexts in the internal narratives to attest to Umar's spiritual power. Others have less specific moorings in the chronicles and do not reinforce the Umarian mission. Rather, they reflect recurrent motifs in West African literature and suggest that a common cosmology underlay the ideologies of Islam and traditional religion; that cosmology could appropriate the highly polemical jihaad to its accommodationist impulses. For this reason, and because of the inherent difficulties in interpreting supernatural phenomena 45, it is appropriate to put this body of material in the category of mixed evidence. The major miraculous phenomena associated with the Umarian jihaad are given in Table 3.

|

Miraculous Phenomena Associated with Umar |

|||||||

|

|

|

||||||

| Signs |

|

|

Griot | Talibe narratives | Umar's works | Other | |

|

|

|||||||

| Birth at time of Futa Toro jihad against Cayor |

|

|

|||||

| Birth causes brackish water to become fresh |

|

|

|||||

| Umar fasts in first monthly by nursing only at night |

|

|

|||||

| Umar refuses to work in family fields, walks on water to escape |

|

|

|||||

| At school, Umar refuses to gather wood with pupils |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||||

| Umar bests scholars at Al Azhar |

|

|

|

|

|||

| Umar heals mad son of Damascus ruler |

|

|

|

||||

| Umar heals Sharif of Hijaz by casting out jinn |

|

|

|||||

| Umar refuses prayer with Imam he knows was not circumcised |

|

|

|||||

| Temptation by the devil |

|

|

|||||

| Refusal to look for gold coffer |

|

|

|||||

| Calming Red Sea waters |

|

|

|||||

| Foiling assassins in Bornu ; famine later visited upon Bornu |

|

|

|||||

| Providing water to troops on Sokoto campaign |

|

|

|||||

| Vision of Alfa Amadu, Muhammad Bello et al. in Sokoto |

|

|

|||||

| Baby Amadu cries at Umar's blessing in Maasina |

|

|

|

||||

| Foiling assassin around Segu |

|

|

|||||

| Umar's hut will protect town of Kangaba |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||||

| Foiling assassin in Jolof |

|

|

|||||

| Woodcarver goes mad trying to remove tombstone of Umar's parents in Halwar |

|

|

|||||

| Meeting and call of Alfa Umar Cerno Baïla Wan |

|

|

|

||||

| Sumptuous feasts for guests at Jegunko |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||||

| Umar mediates at Dingiray while Tamba attacks |

|

|

|||||

| Fire prevents Tamba from entering Dingiray |

|

|

|||||

| Elephant startles Tambans |

|

|

|||||

| Umar puts Tambans to sleep |

|

|

|||||

| Umar's wife Fatima remains imperturbable during attack |

|

|

|||||

| Prayer beads encourage talibe in siege of Tamba |

|

|

|||||

| Prayer beads bring victory at Menien |

|

|

|||||

| Umar provides food for hungry army in Upper Senegal |

|

|

|||||

| Umar dries up river bed to permit crossing in Upper Senegal |

|

|

|||||

| Umar tames jinn and sorcerers of Jakhunu |

|

|

|

|

|||

| Umar provides water for thirsty army in Karta |

|

|

|||||

| Foiling assassins in Futa Toro |

|

|

|||||

| Umar makes mosque shake in Futa Toro |

|

|

|||||

| Umar provides water for thirsty army at Bassaga |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||||

| Umar provides water for thirsty army at Markoya |

|

|

|||||

| Umar changes from yellow to black robe to protect self against Segu magic |

|

|

|||||

| Umar makes rain stop temporarily at Jabal |

|

|

|||||

| Great dust clouds at Sansanding |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||||

| Amadu III makes rain come. Umar keeps powder dry |

|

|

|||||

| Mountains tremble and river floods at Cayawal |

|

|

|||||

| Umar and talibe walk through fire to escape siege |

|

|

|||||

| Umar and talibe walk past sleeping Maasinans to escape |

|

|

|||||

| Opponents kill serpent of Umarians by sorcery |

|

|

|||||

| Umar's horse guides Tijani for reconquest operation |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||||

| Umar as master of jinn | ï | ï | |||||

| Umar tries to see a robe which assures Paradise | ï | ï | |||||

| Umar enlists jinn of Samba Rutta to fight for him | ï | ï | |||||

| Umar give ritual protection against pain of death |

|

ï | |||||

| Umar asks for blessings on his family |

|

ï | |||||

One cluster of these stories consists of miraculous signs of the election and power of Umar, loosely attached to his birth, childhood, pilgrimage, and visits to the states of Bornu and Sokoto. Umar was the source of many of these proof texts, both through discussions with his followers and by the works he wrote during the period of the 1830s and 1840s 46.

What I call the « orthodox miracles » are embedded in the narratives of the jihaad and occur in emergencies related to the environment, such as thirst and hunger, or created by the enemies of the movement. Umar succeeds in obtaining divine intervention to overcome the crisis and thereby demonstrates the support which he enjoys from the founder of the Tijaniyya, the Prophet, and ultimately God. The favourite formula consists of a period of meditation set between the recognition of the emergency and its resolution 47. Umar emerges from his retreat, reveals his authorization from on high, and sets the situation right. In the minds of the Umarian community, meditation and miracle were closely linked and served to confirm the conviction of participation in a divinely ordained mission.

The « unorthodox miracles » never appear in the internal chronicles. In them Umar may take the form of an animal and consequently soil the image of God in man. He may issue a curse and thus unfairly manipulate his spiritual resources. He may seek the support of subordinate divine forces to struggle with divine but evil powers, thereby calling into question the omnipotence of God. As one might expect, these events appear in the accounts of griots, who have little concern for the theological implications of the jihaad but great sensitivity to entertainment value and the eclectic religious belief and practice of their listeners.

The griots enjoyed a freedom to criticize their patrons and ultimately to change patrons. While some attached themselves closely to the Umarian leadership and integrated chronicles into their recitations 48, many retained their conventional autonomy. More recently, with the decline in power and wealth of the chiefly estate during the colonial period, the oral historian has begun to travel more widely, cultivate relations with a broader clientele, and develop a repertory to cater to a wide variety of audiences. The Umarians who paid the fiddler in the mid-nineteenth century can no longer call the tune.

Consequently, many griots take some liberties with the tradition of Umar and the jihaad 49. Without adopting a position of hostility, they enliven their accounts with stories offering a variety of perspectives. These stories often fit the rubric of 'unorthodox miracles', as the following sample, about the death of a serpent and the revolt of Masina against Umar, illustrates:

Bekkay [Ahmad al-Bekkay], notified of the revolt, went towards Hamdullahi [occupied by the Umarian forces]. He stopped for meditation and saw in his vision that Umar possessed two powers, one in heaven and one on earth. The second power came from a long serpent; Umar, if he saw the serpent surrounding the town in his meditation before the attack, knew that he would triumph. Bekkay saw that he could kill the serpent and did. In Hamdullahi Umar realized what had happened and that his cause was doomed. Umar said:

« Bekkay has done evil to God, Tijani [the founder of the Tijaniyya] and me. He has prevented me from realizing my goals. Amadu ibn Amadu [Caliph of Masina, killed the previous year] is in the presence of the Prophet poisoning my name. I am going there to defend my name. » 50

The story carried a certain measure of reassurance for friends and foes of the jihaad. It said that Umar was dead, circumventing the enforced silence of the Segu court 51. It said that he had gone with dignity and that the onus for manipulating divine forces was on his opponents. It assimilated Islam to older myths and prepared the listener to accept destiny and the larger forces of heaven and earth. In similar fashion, the miracles which attested to Umar's divine election and power were important articles of faith for the talibe. Without this initial belief they would not have accepted Umar's assurances of Paradise and might never have enlisted in the jihaad. The historian can use these supernatural statements to understand contemporary belief and motivation, subsequent interpretation, and the cosmology common to all sides of the struggle.

At first blush it might seem superfluous to scrutinize the nature of the French material 52. Almost all of it is dated, located and tied to a particular author-virtues which much of the African evidence can scarcely claim. It cannot be wisely used, however, unless its origins and purposes are assessed. This involves an analysis of the French presence in the mid- and late nineteenth century in the Upper Senegal valley, the principal arena of contact with the Umarian forces.

The European officials who wrote most of the archival and published accounts consisted primarily of commanders of permanent forts at Bakel, Senudebu and Medine and persons on special geographical, diplomatic, and military assignments. Rarely did they possess skills in Arabic and local languages, familiarity with local custom, or the inclination to pursue anthropological or historical inquiries. As a result, they relied on local Africans for much of the information which they communicated to their superiors 53.

One fund of information consisted of the Senegalese traders who worked the commercial networks of the Upper Senegal valley. Umar and his successors depended upon these men for critical supplies of guns and powder, particularly through the market at Medine. As a result, the traders often had accurate news about the jihaad and the Umarian state. They were not always eager to divulge their insight, especially when the French planned military expeditions which threatened long established relationships and the profits of the trading season. At the same time, since they depended upon the French for protection they could often be coerced into revealing what they knew 54.

Other Africans in the Upper Senegal arena were more favourable to French expansion. This was particularly true of the employees who served the colonial administration as interpreters, telegraph and railroad agents, supply clerks, and the like. They tended to spend many years in a post, knew the surrounding area well, and quickly seized the opportunity to initiate and, where possible, control the new European official 55. They might grow wealthy from booty from French expeditions or by controlling the flow of information. They were inclined to relate what their superiors wanted to hear or what would benefit their own careers, knowing that loyalty was more important than accuracy in gaining promotion. For them, expansion meant advancement since it extended the colonial networks to new posts and created new ranks in the hierarchy.

A striking example of upward mobility in the Upper Senegal is the case of Mademba Seye, a Wolof graduate of the « School of Chiefs » in St Louis and an employee of the telegraph service as of 1869 56. After the French established their colonial administration in the Soudan in the 1890s, Mademba became chief of Sansanding province. Lieutenant Gaston Lautour offered these impressions of Mademba in 1899:

Mademba is Wolof. As such, he is anathema to the natives, incensed at having a despot of a rival nation imposed on them. Installed just after the conquest, as a reward for the aid he gave us, he has managed to avoid riots, rebellions and risings. Having at last become rich, he has accumulated in his fortress numerous slaves, herds, guns and munitions... 57

More than a few employees followed the same path of demonstrated loyalty and touched similar, if less conspicuous rewards.

European officials also obtained intelligence from the chiefly families adjacent to their posts and from refugees from the interior. Both groups tended to oppose the Umarian jihaad and state. They often pressed for expansion to restore or enhance their own position. In each of the three posts in the Upper Senegal, French fortunes were closely tied to a local dynasty. The most important instance for purposes of this essay was the relationship at Medine in the Khasso kingdom, where Governor Faidherbe and King Juka Sambala established a treaty of alliance in 1855 to counter the Umarian threat 58. Juka and his family remained critical determinants of French knowledge and policy for the rest of the century. The refugee community included some exiled royalty, such as the Kulibali of Karta who had been displaced by the jihaad, 59 and slaves who had fled from exacting masters. The French often recruited them as agents for secret missions within the Umarian state 60.

A final category of African collaborator consisted of the military personnel organized in various support services and, most visibly, in the Senegalese Riflemen's Corps. The vast majority of these men had been slaves in the indigenous societies and had low status in the tiny community of the post. Confined to barracks and military routine, they had little opportunity to acquire or communicate information, but they did spread a negative image of the social structure from which they had escaped 61.

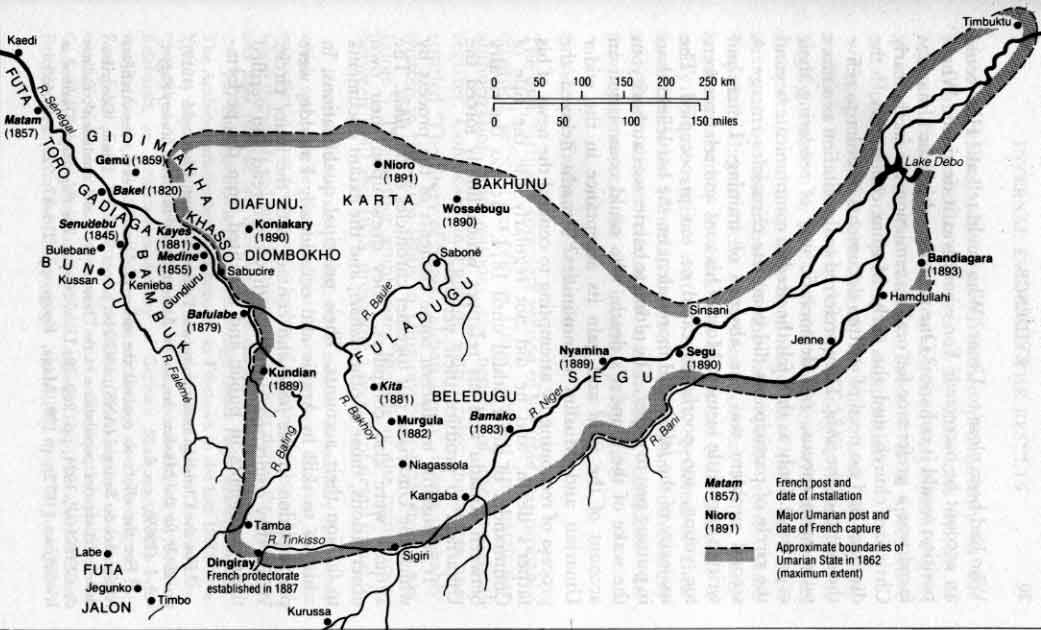

This structure of intelligence existed throughout the mid- and late nineteenth century, but it must be put into a chronological framework to be fully useful (see Table 4). Until 1854, the French conducted a holding operation in the Upper Senegal which depended on good relations with local and regional authorities. Officials were intent upon maintaining commercial ties and collecting information. Bakel served as the basis for several explorations in the 1840s and 1850s which provide a base line for judging Karta and Mandinka societies on the eve of the jihaad 62.

Table 1.4

French Documentation on the Umarian Jihaad and State

| Characteristic activity | Dates | Permanent posts | Comment |

| Commercial operations predominantly | Up to 1854 | Bakel (1820) Senudebu (1845) | Limited post data; important explorer accounts (Raffenel, Hecquard) |

| Military expansion and commercial operations | 1854-60 | Bakel, Senudebu, Medine (1855) | Abundant post data; correspondence w. chiefs; some exploration; hostility |

| Commercial operations predominantly | 1860-78 | Bakel, Senudebu Medine | Limited post data-, important explorer accounts (Mage, Soleillet) |

| Military expansion under Commandant supérieur | 1878-93 | Bakel, Medine, Bafulabe (1879) Kita (1881) Bamako (1883) |

Routine post data; expeditions and secret missions; early ethnography; hostility |

| Colonial rule ('Soudan') | 1893ñ | Medine, Kayes (1891) Nioro (1891), Bamako Segu (1890) Bandiagara (1893) | Systematic ethnography with interviews and document collection; authoritarian but less hostile |

A period of expansion followed under the leadership of Louis Faidherbe. The Governor erected the fort at Medine (1855), conducted an unsuccessful experiment in gold-mining in Bambuk (1858-60), and established a network of « Mande speaking » allies — such as Juka Sambala — opposed to the Fulɓe of the jihaad. His initiatives coincided with Umar's expansion into the Upper Senegal, with two principal consequences for the documentation. On the one hand, French material is indispensable for the reconstruction of the campaigns of 1854-9. On the other, the competition for control of the valley injects an attitude of hostility into the accounts. The local allies, encouraged about recovering territory lost to the Umarians, often supplied false information in the hopes of precipitating European intervention 63. In recognition of this danger, Faidherbe sent a number of his lieutenants on exploring missions 64, but he also manufactured his own propaganda to counter the appeal of the jihaad 65. It is ironic that the image of an intransigent Umar, largely generated by the French, has been retained and belaboured by modern Senegalese nationalists anxious to portray the Fulɓe leaders as a hero of resistance to European conquest 66.

The time of confrontation gave way abruptly to commercial collaboration in the 1860s and 1870s. The French, after their expensive failure at gold mining, confined their territorial imperatives to the peanut-producing regions of the coast. The Umarians, losers in the epic battle at Medine in 1857, settled for control of the area east of the Upper Senegal, with recruitment and trading privileges to the west. An 1860 agreement calling for mutual respect and encouragement of trade expressed the operative relationship, although it was never ratified by either side 67. Two very important explorer accounts mark the beginning and end of this phase:

The letters of the Commandant of Medine draw heavily on the experience of the merchants and document important internal developments in the western parts of the Umarian state.

A new period of French expansion began with the conquest of Sabusire in 1878. Thereafter, under the leadership of Commandants Supérieurs for colonial Soudan, the French conducted annual campaigns during the dry season, whittling away at the Umarian domains until they took the capitals of Segu (1890), Nioro, (1891), and Bandiagara, (1893). In this phase, traders were often excluded from newly-conquered areas and post reports became routine. The most valuable information comes from the staff of the Commandant Supérieur, but it suffers from the same attitudes of hostility which characterize the documentation of Faidherbe's term. Unable to gain the trust enjoyed by Mage and Soleillet in their relations with Segu, officials relied on the intelligence supplied by their subordinates, secret agents, exiled thieves, and former slaves. On occasion, the ambition for promotion of a man like Louis Archinard led to the deliberate falsification of evidence 68. At the same time, the conquest of Bambara and Mandinka areas that had been subject to the Umarian regime led to the recovery of important testimony from the victims of the jihaad 69.

Conquest gave way to colonial rule in the 1890s. Suddenly the French faced the task of administering a vast area with a small staff and little knowledge. They made extensive use of royal allies and subordinate personnel like Mademba. They brought in additional Europeans, some of whom acquired sufficient familiarity with their jurisdictions to become pioneers of West African anthropology and history 70. The principal concern was now law and order. The rulers hastened to identify, count and describe the populations under their control, collecting a great deal of oral tradition and Arabic documentation in the process 71. The descriptions and traditions suffer from haste and an absence of critical method, but they do provide an important baseline for the societies at the turn of the century.

The value of the French evidence is directly related to the quality of the original testimony, the reliability of the chain of transmission, the concerns and abilities of the European authors, and the general context of relations with the Umarian state. The periods of French expansion and competition with the Fulɓe regime generated greater quantities of data, as the Masina conflict did for that phase of the jihaad, but greater insight often comes through the accounts written in times of relative peace and commercial prosperity. The absolute chronology in all the material is invaluable and compensates for glaring weaknesses in many of the other sources, but it is mainly applicable to the middle jihaad of 1854-9 when Umar was operating in or close to Senegambia.

F. External Evidence: The African Materials

The African external material comes primarily from two directions:

Members of the chiefly estate and their griots supply the dynastic perspective. Some of their testimony was given to the French in the nineteenth century in the circumstances described in the previous section; some has been recorded in the last twenty years 72. The accounts deal with the Umarian impact in one area rather than the jihaad as a whole. The best-known corpus comes from Khasso, the kingdom caught between the Umarian and French spheres of control. The chiefs such as Juka Sambala developed a clear rationale for their collaboration with the French. They acknowledged their submission to the Umarians in 1854, but claimed that the Fulɓe violated their understanding of the relationship in two ways: by infringing on the internal autonomy of the dynasty and by raiding the Senegalese Muslim traders who had long frequented the Khasso markets 73. An equally developed tradition comes from Segu. The initial formulation of the griots of the displaced Jarra kings has now spread to a variety of informants in the Middle Niger region. These accounts explain the conquest of Segu in terms of Umar's magical power, rather than his military strength, and emphasize the revolts against Umarian rule in the later period 74.

The theological statements focus on the justification for jihaad rather than its impact. Some Sufi clerics expressed their refusal to participate in terms of the corrupting effects of power 75. More complex arguments were formulated by the Kunta leader, Ahmad Al-Bekkay, who also figures prominently in the Masina material. Al-Bekkay perceived the threat which Umar posed to Kunta hegemony as early as the 1830s, and he organized his criticisms along two principal lines: the « heretical » claims of the Tijaniyya, especially the almost infallible status assigned to the founder and his agent Umar, and the political compromises and injustice which ineluctably ensued from the military jihaad. In one letter addressed to Umar he warned that jihaad leads to kingship and kingship to oppression; our present situation is better for us than jihaad, and safe from the error to which jihaad leads 76. Such statements were grist for the mill of Faidherbe's propaganda in the 1850s and for the francophile clerics that he cultivated in St Louis 77.

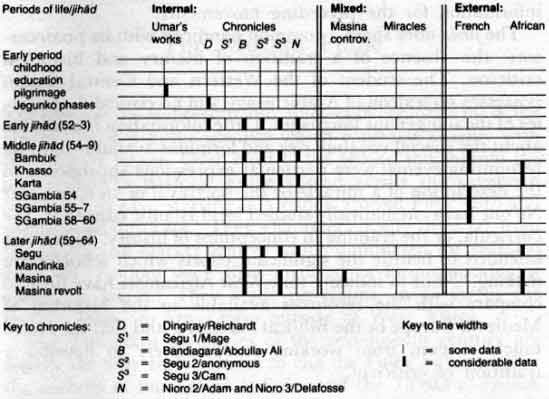

The various sources and categories of sources, together with the analysis of original testimony and transmission, do not add up to a complete data base. More oral evidence from a variety of perspectives could be collected. Additional Arabic material is undoubtedly available in personal libraries, while the enormous « Archinard » collection in Paris will require extensive scrutiny for years to come. Moreover, the material discussed in this chapter is very unevenly distributed, as Table 1. 5 indicates. None the less, for every period of the jihaad it is possible to find both internal and external perspectives, on the one hand, and both informal recollections and more intentional statements, on the other. This is a sufficient basis from which to undertake a new synthesis of the Umarian jihaad.

Table 1.5 Summary of Source Coverage for Umar's Career and Jihaad

Taken together, the sources for the Umarian movement differ significantly from those available for the Fulɓe jihaads of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The contemporary accounts, essentially French or French-mediated, are much richer. The received tradition is not unified and consistent, as is palpably the case for Northern Nigeria and Masina. The partly overlapping, partly independent chronicles, when properly compared and analysed, yield a great deal of insight into the process of jihaad. In addition, the Umarian movement is accessible to new inquiry. Since the campaigns occurred in the mid-nineteenth century, it is still possible to find elderly informants whose parents and grandparents participated in the events. Their recollections constitute a vital complement to the earlier recordings, which often dwell on military history and the concerns of political and religious leaders. By comparison, it is very difficult to find new information for the preceding movements.

The jihaad does share a common handicap with its predecessors: the absence of a tradition of literary and historical criticism. The student of the Western and Central Sudan possesses no lexicon of Arabic usage and no critical dictionaries of the indigenous languages. Little information is available about the special vocabularies and formulas available to those recounting events: were particular expressions appropriate to the description of a miracle or the portrayal of an opponent? No one has systematically studied local Islamic education, the curricula, or the training in conceptions of history. This is not intended to belittle the significant efforts which scholars are making, 78 but to indicate that West Africanists have little to compare with the resources available to the historian of Medieval Europe or the Biblical narrative, and that they have much to gain from working co-operatively to develop a tradition of criticism.

Notes

1. Jack Goody, The Domestication of the Savage Mind, 1977, pp. 152-3.

2. I have used the categories of caste and estate developed by Abdoulaye Bara Diop (La société wolof, 1981, pp. 33 ff.) to shape this section.

3. The word « griot » appears in European accounts of the Senegambian coast as early as 1637 and may come from the Wolof word for traditionalist, gewel. R. Mauny, Glossaire des expressions et termes locaux employés dans L'Ouest Africain (Dakar-IFAN, 1952), p. 40. The principal category of griot in most of the relevant Western Sudanese societies is called gawlo in Fulfulde, jeli in Mandinka and Bambara, and jaari or jarijo in Soninke. The maabo is a griot with similar functions and attachments but descended from weavers who, at some point in the last few centuries, ceased to weave. The bambaaɗo is a griot attached to pastoral Fulɓe patrons. For a general description of the artisan and griot stratum, see P. Curtin, Economic Change in Precolonial Africa (1975), vol. 1, pp. 31-4.

4. Anne Raffenel, Nouveau voyage dans le pays des Nègres (1856), vol. 1, p. 164.

5. A. Lord, The Singer of Tales (1960), pp. 13 ff. For a useful description of the training of griots in the Gambia, see G. Innes, “Stability and Change in Griot Narratives”, ALS 1973.

6. The best and most detailed description of the process is Mervyn Hiskett's treatment of Uthman dan Fodio in The Sword of Truth (1973), pp. 15-58. For the transmission of learning in one lineage, see I. Wilks, “The Transmission of Islamic Learning in the Western Sudan”, in Goody, ed., Literacy. See also Stewart's description of learning in Southern Mauritania (Social Order, pp. 28 ff.) and Eickelman's description for Morocco (“The Art of Memory: Islamic Education and Its Social Reproduction”, CSSH 1978).

7. T. Hunter, “The Jabi Ta'rikhs: Their Significance in West African Islam”, IJAHS, vol. 9, no. 3 (1976), p. 440. See also his thesis, “The development of an Islamic tradition of learning among the Jahanka of West Africa”, University of Chicago, Ph.D. 1977. Karamokoba belongs to the lineage described by Wilks, op. cit.

8. Two partial exceptions are Ahmad Baba, the Timbuktu scholar of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, and Musa Kamara, the scholar of Futa Toro of the early twentieth century. On the first see A. Cherbonneau, “Essai sur la littérature arabe du Soudan”, Annuaire de la Société Archéologique de Constantine, vol. 11 (1854-5), pp. 1-48, and M. Zouber, Ahmed Baba de Tombouctou (1556-1627), sa vie et son oeuvre (1977). On the second, see Amar Samb's introduction to his translation of one of Kamara's works, “La vie d'El Hadji Omar par Cheikh Moussa Kamara”, Bulletin de l'IFAN, B, 1970.

9. Voyage sur la Côte et dans l'Intérieur de l'Afrique Occidentale (1855), p. 328.

10. Ibid., p. 390.

11. See Alfa Ibrahima Sow, “Notes sur les procédés poétiques dans la littérature des Peuls du Fouta-Djalon”, CEA, vol. 5, no. 19 (1965). Other West African languages were also written in Arabic characters and Koranic instruction manuals were composed in the mother languages of the pupils. On the similarities of transmission of oral tradition and Islamic education, see R. Santerre, Pédagogie musulmane d'Afrique Noire (1973), p. 131.

12. Lord, Singer, pp. 124 ff.

13. Essentially the system of analysis suggested by Vansina in Oral Tradition, 1965. El Masri has done this for one of Uthman's manuscripts (see chapter 2, note 50).

14. The distinction between more formal and more informal oral data is advanced by Philip Curtin in “Field Techniques for Collecting and Processing Oral Data”, JAH, vol. 9, no. 3 (1968), pp. 371-6.

15. For the classic statement of the laawol pulaaku or « Fulɓe way » see A. H. Ba and G. Dieterlen, Koumen: texte initiatique des pasteurs peul, 1961.

16. Much of this correspondence and other documents generated during the 1852-64 period is found in the Archinard collection in Paris (BNP, MO FA). Particularly important are two appeals to jihaad (5721, fo. 93, and 5744, fo. 71), a letter from a Trarza Moor follower who had emigrated to Karta (5744, fo. 70), a letter from al-Kansusi of Morocco to Umar (5573, fos. 623) and several letters set in the period between 1862-4 (5713, fos. 33-5, 49 and 56). Umar's letters to the French of June 1847 and October 1854 are in the ANS, 13G 139, pieces 16 and 94, respectively (Arabic original and French translation). Umar's well-known letter to the Senegalese traders, published in French translation in F. Carrère and P. Holle, De la Sénégambie française (1855), pp. 204-7, can be found in the Archives Nationales Françaises, Section Outre-Mer (ANF, OM) SEN. 1-41b (contained in Faidherbe's letter to the Ministry, 11 Mar. 1855). Correspondence between the French and the Umarians based in Konyakary in 1860 is contained in ANS 15G 62.

17. BNP, MO, FA 5732, fos. 23-8. The author was Muhammad b. Mahmud b. Hamat of Nabbaji in eastern Futa Toro. This may be the same document as that attributed by Henri Gaden to Lamin Tafsir Amadu, a maabo of Hayre. Gaden, ed., of Mohammadou Aliou Tyam, La Vie d'El Hadj Omar. Qacida en Poular (1935), p. viii.

18. BNP, MO, FA, 5559, fos. 1-6.

19. BNP, MO, FA, 5683, fos. 150-1. The author was Muhammad b. Ibrahim b. Umar of Labe province.

20. BNP, MO, FA, 5457, fos. 1-4; 5713, fos. 49, 56.

21. M. Khadduri, War and Peace in the Law of Islam (1955), pp. 118 ff.

22. And probably in the Arabic chronicle of the earlier jihaad (see note 18).

23. Those which I call Segu 2/anonymous, Nioro 2/Adam, and Nioro 3/Delafosse.

24. For the Christian community, see Frederick Grant, The Gospels (1957), pp. 28-9; for the Muslim one, see N. Abbott, Studies in Arabic Literary Papyri, vol. 1 (1959), pp. 6-28.

25. For the effort to conceal the news of Umar's death, see Archives Nationales du Sénégal (ANS), 13G 244, pieces 58-62: E. Blanc, 'Contribution à l'étude des populations et de l'histoire du Sahel soudanais', Bulletin du CEHSAOF, 1924, pp. 269-70; U. al-Naqar, The Pilgrimage Tradition in West Africa (1972), p. 120; Mage, Voyage, pp. 216-17, 223, 246, 439.

26. Umarians have also formulated a number of ancillary documents which can often be found in West African personal libraries. The most important of these are lists of the leaders of the jihaad, the sons of Umar and where they died, and miracles performed by Umar during the pilgrimage and jihaad (for the last document, see chapter 3, note 11).

27. The Fulfulde title is Haala Shaiku al-Haji Omaru Fotiyu Kedwiiyu ɓii-Saidi. The Arabic-character text was brought to Freetown in the late 1860s by a Yoruba Muslim who had been studying in Futa Jalon. It was then transcribed in Roman characters and translated into English by Charles Reichardt, an Anglican missionary of German background who was working on the Fulfulde language. The vocabulary clearly belongs to the Futa Jalon dialect of Fulfulde. The Roman transcription and English translation, but not the original text, may be found in the appendices to C.A.L. Reichardt, Grammar of the Fulde Language (1876); see also p. xix and Reichardt's letter in the CMS archives (CAI/0182, dated 30 June 1869).

28. Except for one remarkable episode describing the alienation of a leading Futa Jalon disciple from the rest of the community. See Reichardt, Grammar, pp. 310-13 of the translation, and chapter 7.

29. Found in E. Mage, Relation d'un voyage au Soudan occidental (1867), pp. 139-86. I use the 1867 rather than the 1868 edition of his work. Mage was accompanied by Dr L. Quintin who wrote very little about his trip.

30. Mage, Voyage, pp. 139-40.

31. Soleillet's account has the added disadvantage of heavy editing by Gabriel Gravier, an arm-chair French geographer. See P. Soleillet, Voyage à Segou (1878-9), rédigé par G. Gravier d'après les notes et journaux de P. Soleillet (1887). Soleillet is indispensable, however, for his descriptions of the trials and tribulations of Umar's son Amadu.

32. The Arabic title is Dhikr Ibtidaa Jihaad Shaikhuna. Copies of the Arabic text may be found in the libraries of Alfa Baba Thinbely of Bandiagara, Madani Tal of Segu, and the Fonds Brevié (cahiers 10 and 3) of IFAN. A literal French translation is available in the Fonds Brevié, cahier 10, while a more polished form appears in M. Sissoko, ed., “Chroniques d'El Hadji Oumar”, Education africaine, 1936-7.

33. The dating rests on the following arguments. First, on five separate occasions the manuscript mentions « traditionalists » (ra'uun) whose testimony is being recorded, suggesting that the writing occurred after a certain period of development of traditions. Second, in the pilgrimage sequence, the manuscript mentions two wives of Umar. One is identified as the mother of Amadu and the other as the mother of Habib. This suggests composition after Habib came to prominence in the early 1870s as a rival to Amadu. Third, the document does not mention another son, Muntaga, who became embroiled in another controversy with Amadu in 1884. Fourth, the references to the death of Tijani in 1887 in the Kidira and Bamako versions appear to be later additions to the text. Finally, Dr Colin (“Le pays de Bambouk”, Revue d'Anthropologie, vol. 1, 1886, p. 433) mentions a document written by an Umarian disciple that had been in the possession of a Medine trader a few years before, and which may well be this manuscript. I am indebted to John Hanson for insight into the circumstances of composition of this chronicle.

34. The Arabic title is Kaifiya Shaikhuna... wa Qudumuhu ilaa Bait Allaah ... wa 'Ibtidaa' Jihadihu ila Tamaamihu. B. G. Martin wrongly attributes this document to Tierno Malik Diallo of Kidira in eastern Senegal, who was simply the custodian of one copy of this document at the time Philip Curtin made a microfilm of it in 1966. See Martin's article, “Notes sur l'origine de la “Tariqa” des Tiganiyya”, Revue des Etudes Islamiques, 1969, p. 269. The chronicle was apparently consulted by Henri Gaden in the preparation of the translation mentioned in note 36 below. Gaden, ed., Qacida, pp. vii, 21, 50, and 79.

35. I have found copies of the manuscript in the libraries of Madani Tal of Segu, Baka Sylla of Bamako, Malik Diallo of Kidira, Senegal (see note 34), and Seydu Nuru Tal of Dakar, and in the Fonds Brevié (cahier 11) and Fonds Curtin of IFAN.

36. Published by Henry Gaden in a Roman transcription, French translation and French commentary under the title, La vie d'El Hadj Omar. Qacida en Poular (1935).

37. Thiam finished the text some time between 1884 and 1890. The text was apparently even used for instruction in writing Fulfulde. On the details of the manuscript and composition, see Gaden, Qacida, pp. v-ix.

38. The French translations of the Nioro chronicles are available as follows.

39. Nioro 2/Adam.

40. The principal published accounts are A. de Loppinot, « Souvenirs d'Aguibou », Bulletin du CEHSAOF, 1919, and Ibrahima Ouane, L'Enigme du Macina, 1952. De Loppinot was a colonial administrator in Bandiagara and wrote his impressions in 1908, the year following Agibu's death. He makes some obvious blunders that cannot be attributed to Agibu's testimony, such as the confusion of Agibu's mother (from Bornu) with the mother of Habib and Mokhtar (from Sokoto) on p. 38. Ouane (Wan) was a grandson of Agibu. He mixes some Arabic documents and French sources with his grandfather's recollections. Some of Agibu's views emerge in the account of Soleillet (see note 3 1). I collected information from Bougouboly Alfa Makki Tal, another grandson of Agibu, in August 1976 at Bandiagara.

41. Excerpts from Umar's and Amadu's letters are contained in the Kamara compendium (see note 10) and in Ouane, Enigme, pp. 181-3. A sharp letter from Umar to Amadu is found in BNP, MO, FA, 5684, fos. 138-42. I have located two complete letters from Amadu to Umar: an earlier angry epistle found in BNP, MO, FA, 5681, fos. 6-11, and a later conciliatory one, available only in French translation, in ANS 15G 74, last section, pièce 3). The Umarian tract, Bayaan Maa Waqa'a baina Shaikh 'Umar wa Ahmad ibn Ahmad, may be found in BNP, MO, FA, 5605, fos. 2-29, and in the libraries of Madani Tal of Segu and Seydu Nuru Tal of Dakar. Substantial selections from it can be found in the Kamara compendium and in Muhammad al-Hafiz, Al-Hajj 'Umar al-Futi, Sultan al-Dawla al-Tijaniyya (1963). An annotated French translation of the Bayaan has been published by S. Mahibou and J. L. Triaud and published as Voilà ce qui est arrivé. Bayaan maa waqa'a dal-Hajj 'Umar al-Fuuti (Paris, CNRS, 1983).

42. Entitled Maa Jaara baina Amir al-Muminin Ahmad ... wa baina Al-hajj 'Umar. The author identifies himself as Muhammad b. Ahmad b. Ahmad. Fatimata Diarah (in “L'organisation politique du Maasina /Diina/, 1818-1862”, thèse de 3e cycle, Paris 1, 1982, pp. 24-5) suggests that the author may have been Hammadun Abba, qaadi of Sokura. Copies of the manuscript may be found in the libraries of Alfa Baba Thinbely of Bandiagara and Alfa Abdu of Toggel quarter in Mopti.

43. Some of Ahmad al-Bekkay's letters may be found in BNP, MO, FA, 5259, fos. 72-3; 5716, fos. 32-40 and 184, and in ANS 15G 74, last section, pièce 4 (French translation only). Letters to Umar may be found in BNP, MO, FA, 5259, fos. 66-70 (ANS 15G 74, last section, pièce 2, is a French translation of fos. 68-70); 5519, fo. 54; and 5716, fos. 32-40.

44. Amadou Hampâte Bâ has collected a great deal of oral and written tradition in Arabic and Fulfulde dealing with the conflict (for a description, see Alfa Ibrahima Sow, Inventaire du Fonds Amadou-Hampâte Bâ, 1970), in anticipation of publishing a definitive study and sequel to his Empire peul du Macina, vol. I (with J. Daget, 1962), which stops in 1853. Bâ, however, has ancestors attached to both the Umarian and Masina sides of the question and may not be willing to pronounce himself on the conflict in print. Much of Bâ's perspective emerges in the thesis of Diarah cited in note 42.

45. See the comments of Murray Last in his article, 'A note on attitudes to the supernatural in the Sokoto', JHSN, 4.1 (1967).

46. For a list of some of these signs, see J. Salenc, ed. and trans., “La vie d'Al Hadj Omar”, BCEHSAOF, 1918. This is a translation of a treatise found in the Moroccan Tijaniyya headquarters in Fez in the early twentieth century. The author of one part of the manuscript, Ahmad b. al-Abbas, spent a considerable time in Segu in the 1860s. Most of the signs were originally described by Umar in his major work, Rimaah Hizb al-Rahim 'alaa Nuhuur Hizb al-Rajiim, chapters 28-30.

47. The Arabic term is khalwa. Many instances appear in Segu 3/Cam.

48. Amadu Wendu Node N'Diaye, a gawlo of Matam whom I interviewed several times in March and April 1968, fits this category.

49. I would include in this category my own interviews with Ali Gaye Thiam (Matam, Senegal, in February 1974; a maabo), and Hamady Sayande N'Diaye (Matam, in February 1974; a maabo); Philip Curtin's interview with Saki N'Diaye (Dakar, in April 1966; a gawlo); my interviews with Jeli Musa Diabate (Kayes, Mali, in September 1976; a jeli); and a performance at Radio Mali in Bamako by Binta Mandani Gawlo N'Diaye (June 1976; a gawlo). On the freedom of the griot, see L. Makarius, “Observations sur la légende des griots malinké”, CEA, vol. 9, no. 36 (1969).

50. Curtin interview with Saki N'Diaye (see note 49).

51. See note 25.

52. The British in Bathurst, Gambia and Freetown, Sierra Leone had little contact with the Umarian movement. At the beginning of the nineteenth century they competed actively with the French for knowledge and influence in the interior, but at mid-century they restricted themselves to local operations.

53. Ronald Robinson has made the larger point, that Europeans depended upon African collaborators not only for control of the interior but also for information, in his essay, “Non-European Foundations of European imperialism”, in R. Owen and R. Sutcliffe, eds., Studies in the Theory of Imperialism, 1972.

54. French merchants with established interests along the river were also unenthusiastic about French military expansion. See L. Barrows, “General Faidherbe, the Maurel and Prom company, and French expansion in Senegal”, UCLA, Ph.D. thesis (1974), 274-5, and his article, “The merchants and General Faidherbe”, RFHOM 1975, pp. 774-5.

55. Note the remarkable manipulation of Sir Charles MacCarthy in 1822-4 by the Gold Coast Fante who were hostile to Asante. B. Cruickshank, Eighteen Years on the Gold Coast (1853), vol. 1, pp. 145-8. W. Cohen uses an 1887 quote from Gallieni to show the same phenomenon in Mali in The Rulers of Empire (1971), p. 16. Compare Bruce Berman's analysis of informational processes in his work, “Administration and Politics in Colonial Kenya”, Yale University, Ph.D. thesis (1973), chapter 3.

56. See Abd-el-Kader Mademba's description of his father's career in “Au Sénégal et au Soudan français”, Bulletin du CEHSAOF, 1930.

57. G. Lautour, Journal d'un Spahi au Soudan, 1897-9 (1909), p. 263.

58. The relationship between the French and Juka Sambala and the reporting on Umarian events can be followed in the Medine letters in ANS 13G 108-9.

59. The most prominent Kulibali exile was Dama, son of Garan. See chapter 9, section C.

60. Whereas they usually chose traders or administrative employees for official delegations

61. One outstanding exception to the low status of the military was Mamadu Rasin Sy, a member of the nobility of Futa Toro who joined the Riflemen, became an officer and assumed a number of important diplomatic and military assignments in the 1880s and 1890s. Méniaud, Pionniers, vol. 1, pp. 50, 145, 228, 409, 466, 490-4, and 517.

62. The most valuable accounts are Anne Raffenel's Voyage dans l'Afrique occidentale (1846) and his Nouveau voyage (cited in note 4) and Hecquard's Voyage (cited in note 9). No comparable work exists for Segu.

63. A case in point is the information on Umar's Karta campaigns which appears in the Medine letters in ANS 15G 108.

64. The principal accounts are contained in J. Ancelle, Les Explorations au Sénégal, 1886.

65. See the examples of his propaganda in C. Gerresch, “Jugements du Moniteur du Sénégal sur Al-Hajj Umar, de 1857 à 1864”, BIFAN, B, 1973,

66. See Introduction, note 8.

67. The 1860 negotiations are discussed in detail in Y. Saint-Martin, L'Empire toucouleur et la France. Un demi-siècle de relations diplomatiques (1967), pp. 91 -110. See chapter 6, section E.

68. A. S. Kanya-Forstner, The Conquest of the Western Sudan (1969), pp. 176-83.

69. Some of this testimony appears in ANS 1G50, 52, 83, and 115; and ANM ID32, 43, 47, 48, and 51.

70 .The most impressive of the scholar-administrators for the colonial Soudan were:

71. Some of these documents appear in the « Monographies » of the administrators at the turn of the century. One can discern, for example, passages from the Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali chronicle in the essays of Underberg and Briquelot (ANS IG122 and 158). At the same time, the French stimulated some of the local citizens to collect their own traditions, as in the Nioro case (see note 38).

72. Much more systematic inquiries should be undertaken throughout western Mali. I have only collected data in Khasso, Segu, and Masina, and used material collected in Nioro.