The Battle of Medine: Deployment of 21 April 1857 adapted from: Cissoko, “Contribution”

Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1985. 420 pages

When Umar turned back to Senegambia to replenish his army after the exhausting wars of Karta, he encountered a greatly strengthened French presence. Since 1854 his opposition to the Europeans had moved through a spiral of escalation: from the Governor's arms embargo to Umar's trade embargo, from raids on shipping to attacks on the jihadic network in the upper valley. The original structure of the movement, the recruitment of men and material in the “west” to wage the war against the “pagans” in the “east”, was in jeopardy. Umar could not resume his position on the Farbanna mountaintop and arbitrate the destinies of Senegambia, he could not ignore the challenge which the French and their allies had hurled at his mission.

This chapter tells the story of the clash of Umarian and French in the region which they both strove to control. It opens with the dramatic confrontation at Medine in 1857, shifts to the tense manoeuvering along the river valley in 1858-9, and moves to a surprising resolution in 1860. By the time the French won their second great victory over the Umarians in late 1859, at the Gemu fortress in Gidimaka, the structure of the jihaad had been significantly altered. While the basic meaning of “west” and “east” was preserved, the centre of gravity now shifted to the Middle Niger, with Karta and eastern Senegambia in an important but secondary logistical role. The period from Medine to Gemu marks the transition from early to later jihaad and from western to eastern theatre. Most of the encounters of this period are well documented. Internal and external perspectives, archives, written and oral traditions—all converge to put Umar and his movement in striking relief as they stride across the Senegambian stage for the last time.

The decision to turn back to the west was made by the fall of 1856. By that moment the Jawara revolt had been quelled, garrisons and commanders assigned, and the heavy losses of the two previous years assessed. Umar had not yet chosen when to prosecute the jihaad against Segu. For the moment the reigning Bambara king accepted his explanation for the Jangirde garrison and tolerated his new regime. But the Shaikh had to attract recruits and supplies for an eventual campaign in the Middle Niger; he had to support his extended operations in Karta, and counter the growing influence of Faidherbe in Senegambia. If he did nothing to reassert his hegemony in the “west”, he could expect to see the jihaad collapse. If he did not punish the “apostates”, those who once affirmed his cause but now embraced the French alliance, he would lose his power to interpret the meaning of Islam in Senegambia.

Geography and politics led him to Khasso. The principal east-west routes ran between the bluffs above the river, right through the long valley where most of the villages of Khasso lay. Trade caravans, armies, and recruiters had no suitable alternative. It was also where Faidherbe had made his greatest inroads into the Umarian sphere: the fort of Medine high above the river, the destruction of Gunjuru, the alliance with chiefs who threatened the underbelly of Karta and blocked the way to Futa Toro and Bundu. The first Umarian initiative came from Cerno Jibi and Konyakary. In August 1856 Jibi took the small chiefdom of Kontiega and executed its leader, Sani Musa (see Chapter 4, Table 1) 1. In February 1857 he recaptured Kholu, scene of the great victory that opened the Karta campaign, and executed Mali Mamudu. In early April the main Umarian force moved on to the river at Sabusire and drove its chief into exile. Most of the rest of Khasso quickly swung back into the Umarian camp. At this point the jihadists were ready to attack the one remaining centre of resistance, Medine, where most of the surviving signatories of the 1855 treaty had taken refuge with the one local leader who epitomized betrayal of the cause and collaboration with the “infidel”: Juka Sambala Jallo.

The decision to attack Medine has been the subject of considerable controversy in the Umarian literature. The internal narratives maintain that the initiative came from the talibés, that Umar tried to dissuade them and then reluctantly assented 2. They exonerate Umar from responsibility for defeat and thus from any stigma of imperfection. The French, with equal simplicity, assert that Umar sought the confrontation. It suited their purposes to portray the “intransigent” author of the 1855 letter as someone bent on destroying the fort which stood in the way of his boundless ambition. Both views are partly correct. The mujaahid chose to lead his legions through Khasso. He chose the month of April, when the low level of the river and the withering heat would reduce the capacity for resistance to the minimum. He could hardly ignore the danger of a clash at Medine, where the compromised Khassonke would certainly congregate for protection. At the same time, the unanimity of the internal sources suggests that Umar knew the outcome of open confrontation and much preferred the policy of boycott and raid, which he had sustained since February 1855. In the words of the Segu chronicler, the Shaikh believed that “the way to make war on the European is to seize all the routes so that no one goes to their places of trade” 3. The talibés had many grievances against the French and their allies, and they had begun to create their own momentum and priorities within the jihaad. It is clear that they pressed very hard for a direct attack on Medine.

Map 6.1

The Battle of Medine: Deployment of 21 April 1857 adapted from: Cissoko, “Contribution”

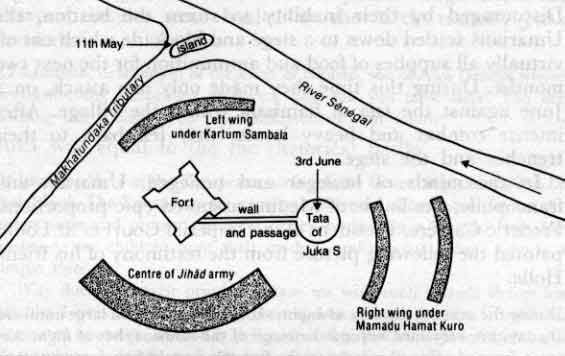

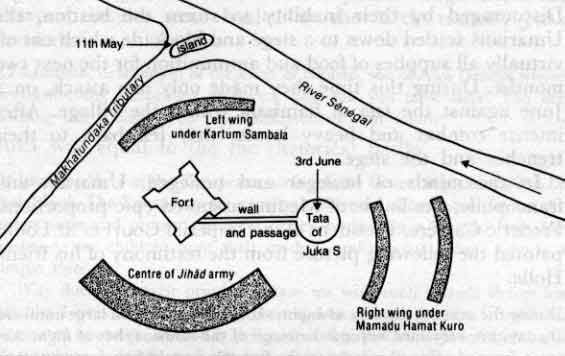

Umar ultimately authorized the attack and encouraged its prosecution as the hot dry season wore on. The battle was joined on 20 April 1857 (see Map 1). About 15,000 jihadists armed with muskets surrounded the village and fort. Inside were perhaps 10,000 persons, principally Khassonke and Bambara, principally old people, women, and children who had fled from their homes. Only about 1,000 could be designated as soldiers. Only 64 of them were trained in the use of artillery and small arms : Commander Paul Holle, 7 European soldiers, 22 Senegalese soldiers, and 34 Senegalese boat-hands with rudimentary military experience 4. Three factors compensated for their overwhelming numerical inferiority : the dominating position of the bluff, the reinforced walls, and 4 canons, which were mounted at the corners of the fort.

The attackers were repelled on 20 April. On 11 May they advanced again. Cerno Jibi succeeded in taking an island in the river close to the fort and capturing a cannon with the range to break down the walls, but a French counter-offensive was able to drive them out in the course of the day 5. Discouraged by their inability to storm the bastion, the Umarians settled down to a siege and blockade which cut off virtually all supplies of food and ammunition for the next two months. During this time they made only one attack, on 3 June against the tata of Sambala within the village. After intense combat and heavy losses, they fell back to their trenches and the siege.

In the minds of besieger and besieged, Umarian and francophile, the battle of Medine assumed epic proportions. Frederic Carrère, President of the Imperial Court of St Louis, painted the following picture from the testimony of his friend Holle:

During the next few days the al-hadjists showed themselves in large numbers. By day they remained beyond the range of the cannons, but at night they crept forward along the rocks to the fort. One could hear not only their voices, one could even understand the words: “Al-hajii, call your friends in Nioro, Futa, Bundu and Gidimakha ! God is great, he is for us. Muhammad is the true Prophet of God, the last to come. He will give us the victory!” Paul Holle, impatient with the cries of the multitude, wanted to make him [Umar] understand the futility of these threats and placed over the gate a sign on which was written the following: “Long live Jesus!!! Long live the Emperor [Napoleon III] !!! Conquer or die for God and the Emperor!!!” 6

The Umarians demonstrated dramatic courage against the fire-power of Medine. Mamadu Hamat Wan, the alleged assassin whom the French had tried to seize in Futa Toro in 1854, lived up to his epithet, “he who does the impossible”, by planting a banner on the top of Sambala's tata before falling to the ground 7. During the June assault the jihadists poured into a hole in the wall, absorbed a hail of bullets and filled the breach with their own bodies. Holle talked to one of the dying men: — Why did your al-hajji not lead the assault? The dying man, casting on Paul Holle a look of profound pity, cried: — My God, my God! I give thanks, I am dying, I see Paradise! 8 In the struggle of words that accompanied the gunshots, the sharpest insults were hurled at the “arch traitor”, Juka Sambala:

— “O Sambala, descendant of the kings of Khasso, son of Awa Demba whose protection the Europeans implored, how low you have sunk! You are nothing but a slave, you have dishonoured your family!”9

Juka was equal to the rhetorical battle:

— “If I am the slave of the Europeans, so much the better. It pleases me to be their slave. The Europeans are generous and good. They have pity on the unfortunate and protect the weak. They never take a woman from her husband, nor children from their mother—unlike your al-hajji, who is a simple thief.

Why does your false prophet pursue me with such hatred? Before his assaults I prayed. Alone among the children of Awa Demba I drank no fermented beverage. But today, tell your al-hajji that in disdain for him and his teaching I drink—and not just wine but brandy.”10

Prayer and alcohol had become potent symbols in the sharply polarized world of Senegambia.

Juka did not rely on French power alone. To his Khassonke and Bambara men he explained that he was using a special cask of gunpowder which had been blessed by the founder of the Islamic state of Futa Toro, Almamy Abdul Kader. Such “Futanke” ammunition, he made them believe, would neutralize the Futanke legions who stormed the tata 11. Such arguments were important psychological fuel in the long months of siege.

The intensity of the rhetoric conformed to the heroism of the struggle. But behind the words and actions was another, more stark reality: the increasing despair of the besieger, the growing hunger of the besieged. The jihadists balked in the face of the withering fire of cannonballs, shrapnel, and bullets. It was only new reinforcements who could be persuaded to lead the June attack. Fresh recruits from Bundu and Futa Toro were intercepted before reaching Medine, and the morale in the blockading army steadily sank. On the other side the picture was equally dim. The defenders had to survive on a diet of peanuts, millet, coffee, and brown sugar. To sustain morale Holle made Sambala believe that a significant reserve of powder remained when in fact he had only one shot per gun. The commander made plans to blow up the fort should the Umarians make one last charge.

In the middle of July the stalemate was resolved. As the water level rose in the river, Faidherbe brought two gunboats and about 800 men to a point only a few miles below Medine. With the help of the cannon of the boats he broke through the trenches, liberated the fort, and put the besiegers to flight. In the succinct and grudging words of the internal narratives, the reinforcements of the Christians came in boats of smoke, whereupon the Muslims abandoned [the siege] and returned to the Shaikh. He said to them: I told you that you could not defeat the cannon 12.

The francophile accounts of the lifting of the siege are more expansive. Carrère's account, written on the basis of Holle's impressions, forms the basis of one tradition. The versions of Juka's family have formed another important strand 13. Two images of the energetic Governor have survived with particular tenacity. The first pictures Faidherbe taping down the safety valves of the furnace so that the steam-powered gunboat could go at full blast through the dangerous shoals of the Upper Senegal 14. The second describes the man with glasses, the “four eyes” with extravision who leads the furious bayonet charge across the Umarian trenches 15.

By the late nineteenth century the heroism and personal force shown by Faidherbe at Medine had become enshrined in a more fabulous legend which had the effect of adding legitimacy to the French domination of Muslim Senegal: “Faidherbe was born in Mecca of a French merchant and an Arab woman. He studied for a long time at the great mosque. It was in Mecca that he became embroiled with al-hajji Umar. Consequently his actions were an acceptable expression of the divine will.” 16

Immediately after lifting the siege Faidherbe sent out patrols into Khasso and inflicted heavy losses on recruits arriving from Futa Toro 17. The strength of the Europeans and the knowledge that reinforcements would soon arrive persuaded Umar to take his army out of reach to the south-east. Consequently Faidherbe had a free rein to eliminate what remained of the Umarian recruitment network in eastern Senegambia, especially after about 500 fresh troops came in early August. He began with Somsom, the fortress near Bakel which had survived attacks by Bokar Sada, the Bakel Commander, and his small artillery. The Governor brought large howitzers and land-mines to break down the walls; so frightened were the defenders that they left by night 18. The French took 400 women and children prisoner, destroyed the structure, and thereby removed an important relay point on the route from west to east. The capture left Bokar in almost complete control of Bundu for the first time. The troops then returned to the east, destroyed the headquarters of Kartum Sambala on the right bank, and put Juka in the driver's seat in Khasso 19.

After these rapid strokes Faidherbe returned to a more traditional mode of operation. Fearful of the toll of the hot and wet season, he sent most of the European troops back to St Louis. He dispatched a gunboat with Bokar and a Bambuk chief to clear the Faleme valley, and then had Bokar installed officially as Almamy in November. The Bundu leader would reside in Senudebu, where the garrison was increased in number to 110, four times its normal size 20. After a fair autumn harvest and a resumption in the gum trade, French prospects in the upper valley looked good at the end of 1857 21. Faidherbe had already obtained authorization for the vast gold-mining operation in the Faleme for 1858, and no obstacles seemed to stand in his way.

The Governor took one more step before settling down in St Louis for the dry season. In concert with his policy of weakening Futa Toro, diminishing its capacity to affect river trade and denying supplies for the jihaad, he built a fort at Matam in the eastern region. He offered no payment for the land, basing his argument on the claim that up to 200,000 francs in goods had been confiscated from inventories in eastern Futa to support the work of Umar 22. When some of the populace protested, he bombarded and burned thirty-four riverfront villages with the cannon of the gunboats. By November the construction was complete; a small garrison and gunboat was posted and a fragile order prevailed. A few months later Faidherbe put his man for all seasons, Paul Holle, in charge of this strategic post.

The Governor also responded to the more fundamental challenge expressed in Umar's letter of February 1855. To blunt the threat and demonstrate that French hegemony and culture were compatible with Islamic piety, he took several steps which reflected his earlier tenure in North Africa. In 1856 he took the “School of Hostages” for sons of chiefs, long used as an instrument of influence and leverage on Senegambian leaders, away from the control of the lay Christian society, the Brothers of Ploermel. He created a more secular curriculum, allowed some Islamic instruction, and relocated the classes at the Bureau of External Affairs, an institution patterned on Algerian precedents 23. In 1857 he established a system of “Muslim Justice” consisting of a Tribunal, which tried cases of family law involving Muslims under a judge of Futanke origin, and an Appeals Council 24. At about the same time he reorganized the indigenous troops into four companies of Senegalese Riflemen commanded by French officers and gave them more respectable and flexible terms of service. He made a concerted effort to recruit free men as well as former slaves and indentured servants, who had customarily filled the ranks of the earlier units 25. His most brilliant step was the sponsored pilgrimage to Mecca. In 1860-1 he sent Bu El Moghdad Seck, assessor to the Muslim Tribunal and interpreter at External Affairs, while the following year he sponsored Hamat Njay An, the judge of the Tribunal. Seck became a particularly valuable ally of the French cause. He saw his pilgrimage as a way to counter the “demagogic” influence of Umar 26. All of these measures concerned primarily the population of St Louis, but they had a large echo in Senegambia through the trading diaspora.

It was with the same purpose of weakening Umar and creating a francophile Muslim community that Faidherbe developed an active propaganda machine in the wake of the deliverance of Medine. In one Arabic circular, published simultaneously in French in the newspaper which Faidherbe had started in 1856, literate Senegambians could read:

Al-hajji has indeed made the pilgrimage, but he seeks only his own advancement, women and wealth. And he will substitute that for Muhammad's Sunna, saying he did it as a mujaahid. Al-hajji has indeed made the pilgrimage, but he turns away from the path to have his wealth. He would change the Sunna of Muhammad's guidance and stray from the path in his jihaad 27. The Governor lost no occasion to remind his audience of the traditions of tolerance of France, the violence of jihaad and the opposition to it by prestigious clerics like the Kunta 28.

While these policies were often patterned on the earlier French experience in Algeria, they did represent an intelligent response to the challenge posed by Umar. They gave some legitimacy to Muslims who operated within the French sphere. They weakened the ethnic equation which the French had often made between “fanatic” and Tokolor and the religious equation which the Shaikh was trying to establish between piety and jihaad.

A glimpse at the Umarian camp after Medine would have done nothing to shake Faidherbe's confidence that he had established French hegemony in the upper valley. The jihaad had lost 2,000 of its bravest soldiers in the siege and rescue of Medine 29. The army had little food and little prospect of any before the autumn harvest, and it lived in fear of the return of the “boats of smoke”. In the face of these conditions many of the survivors deserted in late July and August, bringing the total force down to about 7,000, less than half of what it had been a few months before. To make matters worse, the garrisons in Tamba and Nioro were on the defensive while those in the upper valley had gone into hiding. The very survival of the jihaad was at stake.

It was time to retreat and regroup. Umar told his disciples that they would “hide in the hills” until their “bodies recovered their strength” 30, and in August he led them up the Bafing River to Kunjan, a village which they had briefly occupied in 1854. This movement allowed the jihadists to avoid the French, whose boats could not pass the rapids of Khasso, and any Kartan enemy anxious to exploit their weakened position. In the Bafing they faced no opposition whatsoever. They could easily confiscate the grain and livestock of the dispersed settlements and chiefdoms. They could control local gold production, re-establish ties with Tamba and obtain weapons from Sierra Leone. They spent the last five months of 1857 convalescing in Kunjan, where they built a solid fortress of mortar and stone. The new bastion replaced Gunjuru as the link between the southern and northern domains of the jihaad.

With a garrison of several hundred sofas and talibés, it fulfilled its functions of liaison, protection of trade, and raiding base until the French conquest of 1889 31.

The recovery of body and spirit took some time. The jihaad was now obviously vincible and vulnerable. Many of its pillars had been martyred, others had been posted to key locations in Karta. Most of the Kunjan community had little indoctrination in Tijaniyya ways or the imperatives of jihaad; they were not prepared for times of tribulation; they had not been moulded into a cohesive unit. These problems of commitment surfaced repeatedly. On one occasion Umar carried rocks for the construction of the fort to set an example for the talibés, grown accustomed to slave labour. Some followers began to steal from others, some began to encourage desertion from the ranks. In these conditions Umar relied heavily upon his kinsmen from Toro, who stood guard around the camp, and he intensified his rhetoric and promises: “I swear by the highest authority that the army is fore-ordained by Him who created the seven heavens and the seven earths, and that it cannot be destroyed by infidels or hypocrites or libertines until the coming of the Imam, Muhammad the Mahdi.” 32. This was his only documented reference to the Mahdi, the rightly guided one who would come at the end of time, and its use suggests the desperation and determination of Umar to forge ahead with his mission.

The Kunjan period had many of the characteristics of the time in Jegunko and Dingiray. Umar was accessible. He was constantly preaching and setting the example. He reasserted his domination of the jihaad in the face of the chastened survivors of Medine. Most of the leaders of garrisons in the north and south visited the fort. Alfa Umar Baila came in from Nioro. Some of the Shaikh's wives, sons, and his nephew Tijani came up from Dingiray, under the care of Alfa Amadu, the older brother of the mujaahid 33. It was an opportunity to create a new sense of unity before launching the second stage of the war.

The logic of the situation now impelled the jihaad towards the Niger. Since the French had established their capacity to control the Upper Senegal, Umar could no longer have free rein over Senegambia's agricultural and commercial wealth. A state limited to Karta and Tamba would not survive: cut off from the more productive lands of the Senegal and Niger valleys and from the supplies of the coast, it would soon dissolve into petty chiefdoms or fall to external control. The solution was to acquire a base in the fertile Middle Niger and link it with the livestock potential of northern Karta, the agricultural productivity of the Kolombine, the recruitment possibilities of Senegambia, and the access to gold and slaves in the south. By the end of 1857 Umar had begun to plan his mission against Segu. He dispatched a contingent of 1,500 men, out of his beleaguered force of only 7,000, to establish control of the Mandinka territories below Jangirde and south-west of Segu. Then he turned his energies back to the west. To succeed against the Middle Niger kingdom and maintain his position from Dingiray to Nioro, he needed substantial recruits, on a scale even greater than that of 1854. The only place to turn for this level of support was Senegambia.

The changed conditions in the “west” called for a new strategy. Umar could not afford another confrontation like Medine. He could not eliminate the Juka Sambalas and Bokar Sadas nor force the French back into the old dhimmi mould. He could, however, preach the corruption of association and dependence on European power by adding the weapon of hijra to the arsenal of jihaad. Hijra was the holy act of removal from opposition and pollution which Muhammad had inaugurated in AD 622 as he went from Mecca to Medina 34. It had not been an important concept in the Umarian move from Jegunko to Dingiray nor in the growing conflict with the patently “pagan” king of Tamba. It had been present by implication in the 1855 letter. Now it was critical to make explicit the doctrine of hijra and to demonstrate the bankruptcy of the once Muslim societies of Senegambia, which were guilty of mortgaging their moral and economic independence to a European official in St Louis. This judgement had to be rendered by Umar with all the authority at his command and tendered particularly to the Fulbe of Bundu and Futa Toro, who identified most closely with the tradition of jihaad and the Islamic state. So rendered and so tendered it might help achieve the scale of support which the new phase of the mission required.

Umar's tactics once again emphasized the dry season, when the European capacity for retaliation was at a low ebb. The Shaikh hoped to move quickly through Bundu and Futa Toro to announce the hijra. He would avoid the posts of Bakel and Matam and the boats in the river, and use Njum Tata in western Bundu to obtain supplies from the Gambia 35. He endorsed the effort of the residents of eastern Futa to build a barrier of rocks and sticks above Matam as a way to delay the French advance at high water 36. After renewing the call to boycott trade with the French and reinforcing the crucial garrisons of Konyakary and Nioro, the mujaahid embarked for Bundu with about 2,000 men.

Umar arrived in the Faleme in March. Bokar Sada immediately abandoned his new Almamyship by fleeing to the Senudebu fort. The Shaikh, with his penchant for the symbolic act, quickly moved to Bulebane, the traditional capital of Bokar's lineage, and there began to call for emigration. At times he used parable to portray his meaning. According to the Futa Jalon chronicle :

he filled a vessel with little stones and walked with it softly. He did not lose any, but put it down to the ground. He filled again another one and carried it with him, running at the same time, and thus lost the stones right and left. He said: “You see, whoever moves now resembles the first example. Whoever stays behind until he is driven by force, he is like what I have shown you by the second example.” 37.

At other times Umar exhorted his audience more directly: “Emigrate, this country has ceased to be yours. It is the country of the European, and life with him will never be good 38.” Bundu and Senegambia were polluted, the good Muslim must take his family and property to the new jihadic society of the east. Where exhortation failed, Umar was ready to coerce by burning homes and crops and kidnapping the hesitant.

The result of his intervention was a massive hemorrhage of the Bundu population which had not recovered from the civil wars of the early 1850s nor the exodus of 1854. Virtually all of the inhabitants, perhaps 10,000 people and including almost every member of the royal house, left for the east in late April and settled on the land around Nioro. In their wake they dragged two cannon abandoned by the Commander of Bakel in an earlier, unsuccessful campaign against Njum Tata 39. The jihadists were jubilant: they had weapons of incalculable value for the Segu theatre, continued access to Gambian supplies and a substantial number of new recruits. Some of the veil of despair from Medine had been lifted.

In the middle of May the recruitment column skirted Bakel. It stopped at the sites of Somsom, which the French had levelled in 1857, and Borde, where the French had twice taken prisoners and sold them in the local market. Umar, by his gestures, was determined to dispel the aura of European power 40. He then moved into Gajaga and repeated his message to the Soninke. Many responded, some by going directly to the east, others by transferring their villages to the north bank. There they could reinforce the embargo on the gum trade and the new network of stations emerging in Gidimaka to replace the grid which the French had destroyed on the south bank 41.

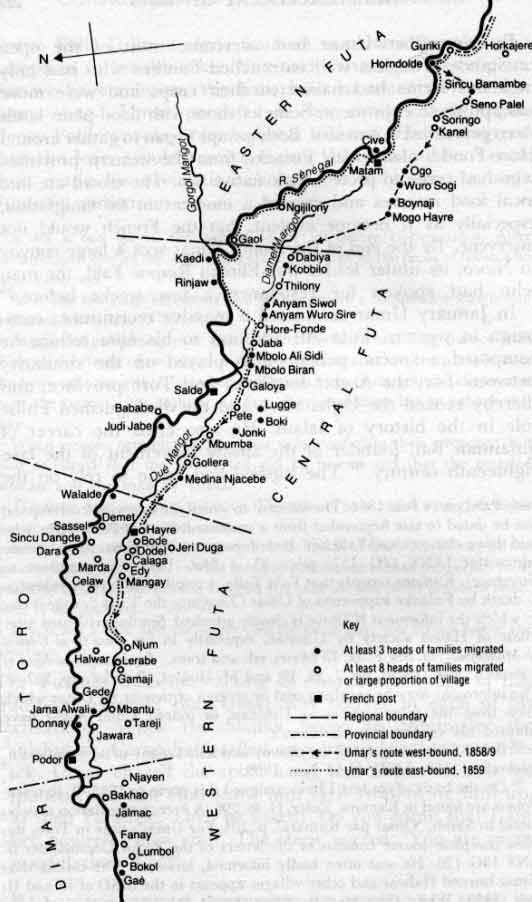

In late May Umar arrived in eastern Futa to generate a massive emigration. The dam still held out the hope of delaying the French advance. The mujaahid spent a month at Horndolde, several miles above the dam, meeting with representatives of the different regions of Futa and exploiting the grievances over the Matam events of the year before. At the end of June he dispatched a convoy of recruits and booty to Nioro. Then he abruptly headed west to the heart of Futa Toro, where he made the ceremonial capital of Hore-Fonde his headquarters for the next six months. In January of 1859 he recruited still further west, in his native Toro, and only in February did he begin to sweep back to the east with the largest single migration which Senegambia has ever known. In June his procession swept through Gidimaka to arrive in Nioro in July—fully twelve months after leaving Horndolde.

For an entire year the leader of the jihaad lived well within the sphere of influence which Faidherbe had carved out for the French, and yet the great antagonists of Medine never clashed. How can one explain. the abrupt movement from Horndolde to Hore-Fonde? How can one explain the absence of confrontation? Only by exploring the priority which both sides put on avoiding conflict and the potential compatibility of the jihadists' goal of hijra, on the one hand, and the French commitment to the exploitation of gold, on the other.

The Europeans did not relish large scale combat with the Umarians in any season. They knew the courage of their opponents. They had barely averted disaster at Medine and made a serious blunder at Njum Tata. More emphatically, the Governor had an overriding goal. He had secured from Paris the support necessary to launch the long-awaited gold extraction in the Faleme Valley 42. In July he mounted the river with a fleet of gunboats, sloops, barges, and floating stables and began to install mining equipment at Kenieba, a Mandinka settlement on the border between Bundu and Bambuk. Kenieba, like Medine in 1855 and Matam in 1857, would absorb most of the Governor's resources in 1858. What he needed was calm, so that his engineers, soldiers, and sailors could work on the mines and machines.

Umar had a different agenda. He needed desperately to convert the civilians of Senegambia into settlers and soldiers for the east. Bundu had made its best contribution, but as in 1854 only Futa Toro could provide the scale of manpower required. Umar convoked representatives from the major lineages and regions to deliberations at Horndolde and repeated his message of hijra. The convoy which departed for Nioro consisted primarily of inhabitants from the eastern region under the spell of the mujaahid's rhetoric and the French aggressions at Matam. The response anticipated from the rest of Futa did not come. Most of the representatives said they would consult their village councils, where Umar could not bring pressure to bear. This was tantamount to refusal and has helped to give Futa Toro, despite its gigantic contribution to the jihaad, a reputation for recalcitrance 43. It also put the Shaikh in a desperate predicament: he could not return to the east with a small harvest of men, nor could he stay on the riverfront in July when the rising water would bring the approach of Faidherbe's flotilla. Consequently he took a bold gamble: he crossed the valley to the higher land and struck west to Hore-Fonde 44. There he would be safe from the French gunboats. There he could exert moral and physical pressure to emigrate.

Faidherbe did not take Umar's decision lightly. He kept informed through his commanders at Bakel and Matam and their networks of informants. He sent two gunboats to anchor in central and eastern Futa, posted Paul Holle to Matam, and put three garrisons on the western edge of Futa to curtail recruitment in the Wolof areas 45. He was determined to contain Umar and, at the same time, to avoid confrontation. In September he left instructions to that effect to his interim replacement: “We must avoid at all costs expelling al-hajji towards the east before our Kenieba installation is complete” 46. In October he wrote a report to his superior in which he stated the goals and risks of his policy:

The danger of this holy war is that Al-Hajj Umar, renouncing open combat with us, in which he failed, now seeks to empty the country around our posts... If he returns to Karta with part of the population of Futa without attacking the Wolof states, we must let him go, then make an expedition against Gemu, and then offer him peace or war as king of Karta. If he manages to carry Futa and invades the Wolof states we must fight him with all the means at our disposal 47.

Having taken his precautions and set down his guidelines, Faidherbe spent the last months of the year in France on leave.

The French did encourage opposition in Futa. They worked primarily through Eliman Rinjaw Falil, the only elector who refused the trip to Farbanna in 1854; Mamadu Biran Wan, the resilient Almamy from Mbumba; and a Tijani teacher from western Futa who had taken strong exception to the jihaad. Hamme Bâ was known as the Madiyu or Mahdi for his radical proclamations and acts back in the 1820s. Now a village chief of limited influence, he served as an invaluable source of information for the French in 1858-9 48. None of the three men realized until November that their European allies had no intention of intervening 49.

At Hore-Fonde Umar had no easy task. He had a relatively small force, perhaps 500 men with several hundred more to ferry recruits and supplies to the east. At the outset he would have to persuade rather than coerce 50. His Futanke audience had a vivid impression of French might, reinforced by the gunboats in the river and the deliverance of Medine. Some of them had been present at the siege and deserted in the aftermath. The economy of the middle valley, in contrast to that of Bundu, was still relatively prosperous. It had not been devastated by civil war and could recover much more quickly, through flood-plain farming, from disruptions like the construction of Podor or Matam. Several lineages from the central provinces had a considerable stake in the economy in the form of land, cattle, and slaves. They shared the reluctance of Juka Sambala and Bokar Sada to cast their lot with a new order, especially one headed by a cleric of modest family from western Futa. Had the French been willing to intervene, or even provide logistical support from the gunboats, this potential opposition might have denied Umar his goal.

The resistance was particularly strong in the early autumn. It was often expressed as attachment to the land. According to a widespread local tradition, the Futanke complained that “they were tired, that they could not go because of the paralyzed one who could not be transported. When Umar asked who the paralyzed one was, they said that it consisted of the floodplain land that could not be carried with them” 51. The established leadership mobilized in defence of privilege. Eliman Rinjaw Falil protested publicly against the pressure to emigrate: “Leave us now. Each who wishes will certainly come with you, and each who does not will stay. He who goes will, upon returning, find us here” 52. He and the other chiefs resented the Toro preacher and the message of equal merit within the jihaad. When Umar sent out the word to “summon all the good Futanke”, they diluted his appeal by translating it “summon all the Futanke of good family”. The mujaahid then made a pointed clarification of his meaning:

He whose father was a good man, and who is also good,

let him come.

He whose father was evil but who is himself good,

let him come.

He whose father was a good man, but who is himself evil,

let him not come at all 53.

The Shaikh had enormous moral authority. On his arrival in Hore-Fonde Almamy Mamadu was automatically deposed. The jihaad clearly superseded the institutions and personnel of the Almamate. This displacement is communicated in the commonplace wisdom of Futa: after Umar there were no more Almamis 54. While in fact heads of state were elected up until the 1880s, they did not command the allegiance of their predecessors.

Umar used his position in the ceremonial capital to great advantage. He began to function as head of state, receiving the tax on harvests and making local appointments. He used gifts of slaves and promises of future wealth to persuade people to emigrate 55. He exploited the presence of the French patrols to drive his message home: “Leave, your country is no longer your own. It belongs to the European, and life with him will never be good” 56. In sum, he succeeded in getting many Futanke to adopt his terms of reference: that a refusal to leave was tantamount to opposition to jihaad and Islam.

The traditions of Futa contain many stories which attest to the authority of Umar, the “evil” designs of the opposition and the growing momentum for hijra. The mujaahid eliminated the mosquitoes in several “loyal” wards of Hore-Fonde, survived the scrutiny of local scholars and foiled several assassination plots 57. One particular account is instructive by its theme of social and religious justice. Umar pressed his case against a polluted society by directly challenging the local authorities.

Cerno Falil Talla, a cleric from an important lineage, took exception to his remarks: “You told us to fight for religion, but we have religion. We have built mosques and we fast every year.” Umar persisted in his charges, whereupon Cerno Falil convoked him before a tribunal. The two agreed that the loser would receive eighty lashes in public. Umar then made his accusations before the judge and a large Futanke audience:

You let a boy go to the age of 18 or 20 before circumcision. After circumcision you let the attendants stare every day at the penis of those who have been cut.

After the marriage ceremony you let the groom's companion watch him deflower his bride.

Instead of protecting your girls, you let the boys host long parties with them at the home of members of the artisan castes. When the party is over the boys take the girl back to her parents on horseback, and the clerics and even the parents say nothing. In fact, they encourage her to behave this way.

When people commit adultery you only confiscate their property, but God ordained that the unmarried girl be beaten and that the married woman and the man be killed.

The tithe does not go to the poor. The tithe of a deceased man goes to his family rather than to the state.

Futa has not respected the mosque as the house of God. Those who do not are condemned to death. For the mosque you should choose the person most qualified to direct the prayer. Instead you take the son of the previous imam, even if unqualified.

If you sell a field and the buyer dies the same day, you do not honor the contract.

The Futanke audience, acting as chorus and judge in this tradition, affirmed that Umar was correct in each of his accusations. When the Shaikh began to administer the punishment, Cerno Falil called on a “spirit [jinn] to cover his back. Umar chased the spirit away and began to beat his opponent. He had God show him Hell swallowing him up, and then Paradise. Then he asked: “Do you admit that I am more powerful than you?” The cleric agreed: “You are more powerful than I.” ” 58.

By November Umar had overcome most of the open resistance. The less well entrenched families who had only highland farms had harvested their crops and were more susceptible to enlistment. Some of those with flood-plain lands were persuaded not to sow. Both groups began to gather around Hore-Fonde, along with Futanke from the western provinces who had come to protect their native son. The crowd ate into local food reserves and created a momentum for emigration, especially as it became evident that the French would not intervene. By the end of the month Umar sent a large convoy to Nioro; its titular leader was Eliman Rinjaw Falil, the man who had spoken for resistance a few weeks before 59.

In January Umar conducted a massive recruitment campaign in western Futa. In addition to his hijra refrain he composed a special poem which played on the similarity between Tur, the Arabic for Sinai, and Toro province, and thereby evoked the Uqba story and the distinguished Fulbe role in the history of Islam. He also cited the career of Sulaiman Bal, founder of the torodbe movement of the late eighteenth century 60. The mujaahid had come to rely on the quantity and loyalty of Toro recruits, most recently in the difficult aftermath of Medine, and he was determined to squeeze his homeland dry of recruits. The long association of Toro with the jihaad and the continuing resentment over Podor made the people responsive to his call. Consequently, by the time Umar arrived, male recruits and families were already assembling at rendezvous points designated by his agents. The Shaikh named chiefs to head the Selobe, Wodaabe, and Ururbe constituencies and to collect the tithe on the harvest at a central depot. For the first time since his departure from Kunjan he felt sufficiently secure to drop his Hausa bodyguard 61.

Map 6.2

Migration from Fuuta Toro by Village, 1846-89 (tentative)

About the middle of February 1859 Umar gathered his followers, loaded his grain, and swept back up the middle valley, leaving behind a region almost as exhausted as Bundu 62. He had fulfilled his expectations of enlistment, but the timing of his departure also had three external motivations. The first came from the French. The garrisons posted on the western border had prevented any effective mobilization in Wolof country. Now Faidherbe was back and about to mobilize his gunboats, which could circulate around Podor at any season 63. It was prudent to move up river and out of reach.

The second motivation came from the electors and eligibles of central Futa. During January Umar had forced ex-Almamy Mamadu to accompany him to diminish the danger of conspiracy 64. Now another group of “conspirators” had united to choose a new Almamy in the hopes of stemming the tide of migration. It was important for Umar to prevent this coalition from consolidating its position and dismantling the stocks of food and weapons placed at Hore-Fonde 65. The final reason was the most compelling of all: urgent messages from Nioro and Konyakary about threats to the state. In particular, a French-supported coalition had taken a heavy toll of the Konyakary contingents and killed Cerno Jibi 66. Any delay now could well spell disaster.

The massive procession followed the highlands to HoreFonde, crossed the flood-plain in Bosseya and swept through the riverine villages of eastern Futa which had been avoided in 1858. In the central provinces he put his men in battle array, named a representative in place of the newly elected Almamy, and marched through the ripening fields of the opposition leaders 67. By this time the “conspirators” had fled to the north bank.

The mujaahid made a special effort to win over one of his foes, the young Bossea elector named Abdul Bokar Kan. Abdul had fought with the jihaad in Bundu, but he abandoned the cause after Medine and returned to Futa. When he received a gift of slaves from the Shaikh in anticipation of the hijra, he promptly sold them and made his refusal known. Now Umar kidnapped Abdul's father and mother in a last effort to enlist the energetic son. The effort failed and Abdul showed his spite by sniping at the column as it moved into the upper valley 68. Moreover, he and the other electors of the central provinces succeeded in their basic design of containing emigration and restricting the confiscation of grain and animals.

In eastern Futa, by contrast, the caravan swept up many a reluctant family and stores of millet and livestock. Some of the resisters were tied by their necks and forced to march. Some small villages disappeared entirely. In short, the country was laid waste on a scale resembling that of Bundu and befitting the message of permanent hijra from pollution which Umar had repeated throughout the year 69. At Matam and Bakel the mujaahid kept his distance from the French and confined his fire to the local refugees. Only at Arondu, where a gunboat protected the Soninke who had refused his call, did he break his rule against confrontation with the Europeans 70. He may have intended to teach a last lesson, he may have hoped to secure more cannon, or the new recruits may have forced his hand. In any case the jihaad paid dearly, with over 200 soldiers killed, for this choice. In June and July the caravan, estimated at 40,000 by the Bakel Commander, made its way to Nioro 71. The Fergo, as the hijra was called in Fulfulde and Futanke tradition, became the watershed of nineteenth century Futanke and Senegambian history.

The French and their upper valley allies had not been idle in 1858-9. Bokar Sada, faced with the prospect of ruling a wasteland, succeeded in getting large numbers of Bundu citizens to return from Konyakary under the protection of the Arondu gunboat. The Medine Commander encouraged desertion and kept communications open to the Jawara, who resumed their revolt in central Karta with the help of a new regime in Segu 72. The Umarian lieutenants faced other revolts, and they had to organize and settle the new arrivals and find sources of food until the communities could produce their own. Cerno Jibi was so frustrated at one point that he responded to a request for aid with the quip: “If my beard is burning, I can hardly help put out the fire burning someone else's” 73. In January he bore the brunt of an invasion coordinated by the French and was killed with many of his men in Tomora. For years he had performed consistently and brilliantly on the critical south-western flank of the state. The news of his death brought Alfa Umar Baila from Nioro and precipitated Shaikh Umar's return from the middle valley.

Faidherbe, after his return in 1859, extended his sway over a weakened and weary Senegambia. He allowed the mujaahid to “empty the country around the posts”, as long as it meant primarily the younger and more turbulent men of Futa and upper valley. The gunboat at Arondu kept the emigrants north of the river and away from the Faleme mining. As the caravan moved east, the Governor established a protectorate over Toro, Hayre, and Halaybe. In the summer he completed another post in Futa, this time at Salde in the centre, brought Mamadu Biran back as Almamy and passed a treaty of protection in the eastern region. The French now had a fort in each section of the middle valley and recognition of their hegemony in the west and east 74. The “fanatic Tokolor” of 1854 had now been effectively domesticated.

In October 1859 Faidherbe delivered on part of his plan of the previous year: he moved against the major Umarian stronghold in Gidimaka. Gemu was the centrepiece of the new north bank recruiting system. It had the added advantage of blocking both the gum trade, which came down from the north to the river, and the desertion of new recruits from Konyakary and Nioro 75. The Governor brought over a thousand soldiers from St Louis and as many allies from the Upper Senegal to a point on the river above Bakel. In scale the campaign resembled those of Podor, Medine, and Kenieba in previous years. After a night march the army attacked the well constructed and heavily defended fortifications under a gruelling sun. Six hours later the artillery prevailed and razed Gemu to the ground.

The toll was high on all sides 76. Umarians numbering 250 joined the list of martyrs, while 1,500 passed into the role of slaves and servants of Bokar Sada and the other “auxiliary” chiefs whose reward it was to share the booty. On the victorious side sixty-seven of the regular troops were dead and 180 wounded, together with an undetermined number of casualties among the allies. Faidherbe glossed over the heavy toll on the basis of his mission to eliminate the Umarian network in Senegambia.

Table 6.1

Approximate Casualties and Prisoners in The Senegambian Theatre, 1855-9a

| Umarian toll |

|

Opponent toll | Figure or estimate | ||||||

| Date | Battle | Statement on killed | Killed | Wounded | Prisoners | Statement on killed | Killed | Wounded | |

| 1854/5 Bakel Theatre |

3/55 | Marsa | 12 | 25 | 4 | ||||

| 4/55 | Near Bakel | some | 50 | some | 50 | ||||

| 4/55 | Bakel | some | 50 | some | 50 | ||||

| 4/55 | Manael | some | 50 | ||||||

|

Sub-total:

|

162 | 25 | 4 | 100 | |||||

| 1855/6 Bakel Theatre primarily |

7/55 | Near Bakel | some | 50 | some | 50 | |||

| 8/55 | Manael | some | 50 | 40 | 10 | 51 | |||

| 7/55 | Horndolde (Futa Toro) | some | 50 | ||||||

| 9/55 | Gunjuru (Khasso) | some | 50 | ||||||

| 10/55 | Gagny | some | 50 | ||||||

| 12/55 | Gege | some | 50 | ||||||

| Marsa | some | 50 | |||||||

| 1/56 | Marsa | 12 | 25 | 4 | |||||

| 2/56 | Somsom | 5 | |||||||

| Dece | some | 50 | |||||||

| 3/56 | Borde | some | 400 | ||||||

| Debu | 100 | ||||||||

| Tulde Yero | 30 | ||||||||

| 4/56 | Nae |

200

|

|||||||

| 4/56 | In Gidimaka | some | 50 | ||||||

| 4/56 | Makha Yakare (Khasso) | some | 50 | ||||||

| 4/56 | Ambibedi | some | 50 | ||||||

| 5/56 | Easane (Khasso) | some | 50 | 50 | |||||

| 5/56 | Senudebu | 60+ | |||||||

| 6/56 | Alana | 7 | |||||||

|

Sub-total:

|

964+ | 25 | 544 | 110 | 51 | ||||

| 1856/7 Bakel and Medine Theatres |

7/56 | In Logo | some | 50 | many | 250 | |||

| /56 | Dramane | some | 50 | ||||||

| /56 | Makhana gunboat | many | 250 | ||||||

| 7-11/56 | Jibi's campaigns | some | 50 | many | 250 | ||||

| 9/56 | Borde | 66 | |||||||

| 2/57 | Kholu | many | 250 | ||||||

| 2-3/57 | Njum | 150 | 140 | 28 | |||||

| 3/57 | Amaje | many | 250 | many | 250 | ||||

|

Sub-total:

|

800 | 206 | 1,028 | ||||||

| Medine battle | 4/56 | Sabusire | many | 250 | |||||

| 2-4/57 | In Tomora | 300+ | |||||||

| 2-7/57 | Medine | 2,000 | 31 | 95 | |||||

|

Sub-total:

|

2,000 | 581+ | 95 | ||||||

| 1857/8 All Theatres |

8/57 | Somsom (Bundu) | 50 | 400 | 27 | ||||

| 8/57 | Kanamakhunu (Khasso) | few | 10 | 800 | |||||

| 8/57 | Ndangan/Sansanding (Bundu) | 75 | 500 | ||||||

| 9-11/57 | In Damga | 34 villages | 500 | ||||||

| 10/57 | Matam | 150 | |||||||

| 10/57 | In Bambuk | 300 | 400? | ||||||

| 10/57 | Farankadu et al (Bambuk) | heavy | 500 | ||||||

| 11/57 | Gidimaka | 30 | |||||||

| 11-2/57-8 | Njum (Bundu) | many | 250 | many | 250 | ||||

| 3/58 | Konyakary | some | 50 | 50 | 50 | ||||

| 3/58 | Tambunkane (Gajaga) | some | 50 | ||||||

| 5/58 | Samba Kanje | some | 50 | ||||||

| 6/58 | Sutukulle (Khasso) | 2 | 6 | ||||||

|

Sub-total:

|

1,467 | 50 | 2,150 | 833 | |||||

| 1858/9 and Fergo Umar | 1/59 | InvasionJombokho | some | 50 | some | 50 | |||

| 1/59 | Tuntare (Tomora) | heavy | 500 | some | 50 | ||||

| 2/59 | Korahamme (Tomora) | many | 250 | ||||||

| 2/59 | Lanel | some | 50 | ||||||

| 4/59 | Matam | 25 | few | 10 | |||||

| Waunde | some | 50 | |||||||

| 5/59 | Idawaish | some | 50 | some | 50 | ||||

| Dramane | some | 50 | |||||||

| Arondu | 220 | 14 | 18 | ||||||

|

Sub-total:

|

895 | 524 | 18 | ||||||

| 1859/60 Gidimaka Theatre |

5/59 | Ahl Sidi Mahmud | some | 50 | some | 50 | |||

| 10/59 | Gemu | 250 | 1,500 | 100 b | |||||

| Komendao | some | 50 | |||||||

| 11/59 | Melga | some | 50 | 400 | |||||

|

Sub-total:

|

400 | 1,900 | 150 | 200 | |||||

|

Total

|

6,688+ | 100 | 4,804 | 3,326 | 364 | ||||

During 1859 the economy of Futa Toro, the Upper Senegal and much of Karta collapsed with exhaustion. The intense polarization between the Umarian and French missions over five years had been costly. Some of the toll had come in battles and skirmishes of the previous years (see Table 1). By my estimates, over 10,000 persons had died in combat and about 5,000 more had been taken prisoner. In addition, both sides to the confrontation had been forcing people into armed camps where they had to abandon their traditional agricultural and pastoral pursuits. The departure of 40,000 people in the Fergo and the demands which their displacement put upon the upper valley finally tipped the balance and produced widespread famine. The French archives leave little doubt about the collapse:

Table 6.2

Echecs of The Famine of 1859/60

| Date | Place | Citation |

| 2/59 | Matam | 5 to 6 people buried each day a |

| 4/59 | Podor | bodies all over the north bank of Dué Marigot at Njumb |

| 6/59 | Bakel | groups of 10 to 15 dead women and children along the roads in Gidimaka c |

| 7/59 | Medine | 30 bodies found under a tree d |

| 8/59 | Bakel | surfeit of hides due to the slaughter of sick and weak cattle e |

| 5/60 | Makhana f | walking skeletons returning from Umarian campaign in east |

5,000 persons took refuge in Gambia and southern Senegal in 1859. Desperate bands of former slaves preyed on even more helpless groups, and instances of cannibalism are remembered in some oral traditions 77. The poverty temporarily levelled the sharply stratified societies of the region. According to a late nineteenth-century recollection from Bundu, “the inhabitants ate only grain, fruits and leaves which they collected in the bush. There was even a moment, and this is well remembered, when Bokar Sada had only one cow at Senudebu which he was obliged to milk to nourish his children and those of his cousins 78. The only persons who did not suffer significantly were the members of the St Louisian commercial community. They often acquired new dependants in the crisis, as this 1862 deposition about pawning attests:

This woman, in the time of famine, was pawned to Bakre Waly, the traitant, by the chief of Nacaga, Semunu [signatory of the 1855 treaty]. Her daughter Dila was sold at the same time to Masherby, ship's pilot at Bakel. He gave her to his mother who, while travelling to St Louis, left her with Mrs Pellegrin. Today the mother wishes to reclaim her child 79.

The exhaustion and displacement, together with the Gemu campaign, ushered in a new era in Franco-Umarian relations. The French were ostensibly masters of land and water. Their forts were functioning, their principal allies alive, their prestige intact. They had been able to pursue the exploitation of Faleme gold. By 1860, however, it was clear that Kenieba was costing too much in money and in the lives lost to climate and disease. The returns were very disappointing, and in the summer the gold-mining operations were closed down 80. At this juncture Paris and St Louis put a priority on the restoration of the gum trade in eastern Senegambia, the agricultural and livestock production upon which trade depended, and peanut-farming in coastal Senegal.

Umar had ostensibly lost the war of confrontation, most spectacularly at the battles of Medine and Gemu. He had, however, succeeded in two of his goals: drastically reducing the trade in gum and other products 81 and massively recruiting the men and matériel for the second phase of his mission. He had laid the basis for continued recruitment by discrediting the Islamic regimes of Bundu and Futa Toro and making the hijra from pollution a crucial standard of Muslim conduct. But the mujaahid could no longer afford to leave his eastern dominions to recruit, nor run the risk of a major encounter with the French. He needed a steady source of arms and men stretching from the Upper Senegal to the Middle Niger, and that could be accomplished only through peaceful relations with his former antagonists.

Faidherbe had considered the option of negotiations as early as his 1858 report to Paris. Umar was suggesting to Moorish traders by the end of 1859 that he was ready to abandon the boycott 82. The deliberations began in June of 1860 when Cerno Musa Ban, the younger brother of Jibi and the new commanding officer at Konyakary, sent envoys to Medine and Bakel. He proposed an arrangement that would recognize French hegemony in Senegambia and up to the Bafing, Umarian control in the east, and the freedom of trade throughout both spheres 83. Faidherbe came to Bakel in August, formulated a draft treaty and had it informally approved by Konyakary. Although the French failed to follow-up the draft with a delegation to seek Umar's approval, and the mujaahid became too preoccupied with the Middle Niger to take any initiative of his own, the arrangements became the working understanding of both sides for the next two decades, and they enabled the Shaikh to shift the centre of gravity of his state to the eastern theatre.

Notes

1. For the attacks before Medine see Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali, pp. 10, 18; Segu 3/Cam, pp. 100-1; and F. Carrère, “Le siège de Médine”, RC 19 ( 1 857), pp. 46-8.

2. On the controversy about Umar's role, the internal accounts are Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali, p. 18; Segu l/Mage, p. 156; Segu 3/Cam, p. 101; Nioro 2/Adam, p. 743; Nioro 3/Delafosse, p. 362, and Segu 2/anonymous. The principal external accounts are Annales sénégalaises, pp. 128 ff., Carrère, “Siège”, and the interview with Demba Sadio Diallo cited in chapter 4, note 59.

3. Segu 3/Cam, p. 101. Umar apparently stayed at Sabusire from April through July 1857 not out of disapproval of the attack but to avoid exposure or coordinate strategy.

4. Carrère, “Siège”, p. 50. The Umarian figures are more subject to dispute. Mage (Voyage, p. 156) and Faidherbe (Annales sénégalaises, p. 135) give 15,000. This is reasonable figure; the losses in battle in Karta discussed in chapter 5 were made up by new recruits from Senegambia in 1857.

5. Carrère, “Siège”, pp. 55-6. See also Annales sénégalaises, p. 130; MSD of 26 June 1857.

6. Carrère, “Siège”, p. 54. 7. Annales sénégalaises, p. 130; Diallo interview cited in chapter 4, note 59.

8. Carrère, “Siège”, p. 54.

9. Ibid. p. 62.

10. Ibid. p. 62.

11. Diallo interview cited in chapter 4, note 59.

12. Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali, pp. 19-20.

13. This perspective is represented in the Diallo interview.

14. Barrows, “General Faidherbe”, pp. 246, 337-8; Diallo interview cited in chapter 4, note 59.

15. Diallo interview cited in chapter 4, note 59; Soleillet, Voyage, pp. 341-2.

16. G. Hardy, Une conquête morale. L'enseignement en Afrique Occidentale Française (1917), p. 304. The same story appears in two of my Mali interviews: with Bokar Cisse on 1 Aug. 1976 and with Mamby Sidibe on 28 Aug. 1976, both in Bamako. A less flattering anecdote from the local oral tradition has Faidherbe playing the role of the imam of Mecca; Umar realizes that the imam is an impostor and uncircumcised, and he exposes the fraud. This emerges in interviews with Fanyama Diabate on 18 Oct. 1975 (by David Conrad), Fakama Kaloga on 11 Oct. 1975 (by David Conrad), both in Bamako, and with Jamme Tunkara, at Nara in August 1980 (by Makan Dantioko). It is also cited in Oumar Ba, La Pénétration française au Cayor, 1976, p. 24.

17. The principal source for the initiatives which Faidherbe took after Medine is Annales sénégalaises, pp. 142 ff. Much of the original material is found in ANS 15G 108 (Medine area) and 13G 167 (Bakel area). During the month of August the Governor left St Louis in an essentially defenceless position. J. Charpy, compiler, La Fondation de Dakar (1958), p. 132n.

18. Annales sénégalaises, pp. 147-50; Rancon, “Le Boundou”, p. 526. Somsom was constructed in the 1820s by Almamy Tumane Sy and was considered impregnable. Malik Samba Sy, one of Bokar Sada's rivals and later an important Umarian figure in the Nioro area, was in command there in 1857 and was keeping prisoner one of his cousins named Alkassum. ANF, OM SEN I 43b (St Louis, 29 Aug. 1857, Faidherbe to MMC). See also chapter 4, note 80.

19. Kartum's capital was Kanamakhunu, near Konyakary. This expedition speeded Kartum's decline as a force in Khasso politics.

20. For the first time Senudebu received a lieutenant as its commanding officer. ANS 13G 247, piece 14 (16 Jan. 1858, Commandant to Governor). Bokar Sada and his lineage usually resided at Bulebane, one of the traditional capitals. His move to Senudebu reflected his insecurity.

21. In March 1858 the French paid duty on gum brought to Bakel by the Idawaish Moors for the first time in several years. ANS 13G 167, piece 69 (20 Mar. 1858, Commandant to Governor).

22. Faidherbe initially claimed damages of 100,000 fr. in a letter to the chiefs of Damga (ANS 3B 96 of 13 Oct. 1857); he made the figure 200,000 fr. in a subsequent note to Almamy Mamadu Biran (ANS 3B 96 of 8 Jan. 1858). His claims should obviously be treated with caution, but they suggest that Umar was still getting considerable supplies through the collusion of the traitants. The detail of the Matam sequence is contained in ANS 13G 157.

23. Denise Bouche, L'Enseignement dans les territoires français de l'Afrique occidentale de 1817 2 1920 (1975), vol. 1.

24. Annuaire du Sénégal, 1860, pp. 74-8; Duval, “Le Sénégal et la paix”, pp. 848-9; Hardy, La mise en valeur du Sénégal de 1817 a 1854 (1921), p. 324.

25. C. Faure. “La garnison européenne du Sénégal et le recrutement des premières troupes noires (1779-1858)”, RHCF, 1920.

26. Robinson, Chiefs and Clerics, p. 106. On Bu El Moghdad's trip, see his article, “Voyage par terre entre cette colonie et le Maroc”, RAC I (1861). On the rationale for the trip, as a measure to counter the influence of Umar, see RAC I (1861), pp. 477-82; Ancelle, Explorations, p. 144; and J. D. Hargreaves, ed., France and West Africa, 1969, pp. 147-50. The sponsored pilgrimage of Senegal coincided with the growth in steamship traffic to Egypt and Jedda. The starting points in Morocco were Mogador and Tetuan. The sea route cut deeply into the overland traffic after 1850. J. L. Miège, Le Maroc et l'Europe (4 vols., 1963), vol. 2, p. 431n.

27. MSD of 27 Apr. 1858. It is also contained in C. Gerresch. “Jugements”, p. 582. For other Faidherbean propaganda see ANS 3B 96.

28. Gerresch, “Jugements”.

29. This figure combines the losses incurred during the siege, at deliverance and in skirmishes around the fort from May to July. Annales sénégalaises, pp. 128-46. It also corresponds to Umar's own estimate, given to some Tishiti Moors in late 1859 or early 1860, which they communicated in turn to the French officer and explorer Vincent. M. H. Vincent, “Voyage d'exploration dans l'Adrar”, Tour du Monde, 1861, III, p. 58.

30. Segu 3/Cam, p. 104. For the Kunjan period the historian is particularly dependent on Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali; Cerno Mamudu Khayar apparently provided Abdullay Ali with the detailed information. See also Segu 3/Cam, pp. 106-7; Segu l/Mage, p. 158; Dingiray/Reichardt, p. 308 of the translation.

31. For the trade with Sierra Leone, see the Mitchell article cited in chapter 3, note 103. For Kunjan, see Galliéni, 1879-81, pp. 587, 606; Mage, Voyage, pp. 45-9; Piétri, Français, p. 161; Saint-Martin, Relations, pp. 366-7, 380-3; Méniaud, Pionniers, 1, pp. 394 ff.; ANS IG 41; and ANM ID 32, section 4.

32. Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali, pp. 20-1. Umar apparently never claimed to be the Mahdi. See al-Bekkay's letter to that effect in 1862 in BNP, MO, FA 5259, fos. 70-1. The one person cited as encouraging desertion is a certain Abdullah b. Bubakr, who is probably Abdul Bokar Kan of Bossea in Futa Toro.

33. Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali, p. 22. Umar had not seen any of his children for three and a half years. This is also the only occasion when his wives could have become pregnant with the children who were born in the late 1850s. See chapter 9, table 2.

34. Apart from the references in the late and highly intentional Segu chronicler (Segu 3/Cam, pp. 27-8, 36-7), hijra, or its Fulfulde equivalent Fergo, first appears in the Umarian literature to describe the recruitment of 1858-9. Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali, pp. 23-4; Kamara, Zuhuur, I, fo. 317; Segu 3/Cam, pp. 109 ff. For Umar's discussion of hijra, see Rimah, II, pp. 209-36, and Willis, “Jihad”.

35. Njum Tata was the home village of Alfa Umar Kaba Jakhite, the Soninke cleric whose support was so vital at Kholu and in the Karta campaign. It was located in western Bundu on the route to the upper Gambia and British posts. Annales sénégalaises, pp. 126, 159; Rançon, “Le Boundou”, pp. 527-8, 533; Segu 3/Cam, p. 55n.

36. About 1,500 Futanke worked on the dam at Garli from February to April 1858. Annales sénégalaises, pp.163-5; ANS 13G 157, passim. Mage's informants ( Voyage, p. 159) suggested that Umar never expected the dam would work and I accepted that judgement in Chiefs and Clerics, p. 45, and then suggested that Almamy Mamadu and perhaps Umar saw the dam as a way of diverting Futanke energies from a direct attack on Matam. It seems more likely, however, that Mage's informants were trying to cover the failure of the project and that the dam was one part of a larger strategy. It is difficult to imagine that Umar would come to eastern Futa in May 1858 if he expected that the French would be able to mount the river less than two months later. The energy expended in the construction of the dam was considerable. ANF, OM SEN I 43d (excerpt from the Journal du Havre, 14 Oct. 58.)

37. Dingiray/Reichardt, pp. 263, 309.

38. Segu 3/Cam, p. 109. Rançon (“Le Boundou”, p. 529) claims that Umar brought forged letters which he claimed were written by Bundu emigrants in Karta and which sought to persuade the people to leave. This is probably a self-serving tradition from Bokar Sada's court. Umar had no need to present forged or authentic letters in order to get an audience in Bundu.

39. On Njum and the cannon, see Mage, Voyage, p. 159, and Rançon, “Le Boundou”, pp. 527-8. On Sisibe participation in the hijra, see Kamara, Zuhuur, I, fos. 159-61. For the 1854 emigration, see chapter 4, sections B and D.

40. Segu l/Mage, p. 159, and Segu 3/Cam, p. 111, are the only internal narratives to mention this important symbolic act.

41. Gidimaka and the north bank were functioning in the same manner as Bundu and Gajaga had in 1854. Faidherbe's offensive in 1855-7 made the Umarians wary of installations on the south bank.

42. The project required substantial additional credits. On the installation, usually identified as Kenieba after the closest village, see ANS 13G 250, passim; Annales sénégalaises, pp. 163-6; Curtin, “Lure of Bambuk gold”; Duval, “Le Senegal et la paix”; Rancon, “Le Boundou”, pp. 454-7. Kenieba required about 1,000 men for the work and the guard duty. In 1858-9 Kenieba had 164 soldiers and Senudebu 147, compared to 61, 64 and 19 at Medine, Bakel and Matam, respectively. ANS ID 12, piece 14 (“Composition des postes, 1858-9”). 43. For example, Salenc, “Vie”, p. 423. See chapter 9, section B.2.

44. The French convoy headed for Kenieba was forced to wait at Matam from 13 to 19 July because of delay in the rising of the river. By 19 July the river had already created a passage through the barrier sufficient for a boat. Umar was at Horndolde, about 50 kilometres upstream, and immediately left for Hore-Fonde, where he arrived 25 July. By using the chronology of the internal narratives for Umar's stops en route (Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali, p. 127; Segu 3/Cam, pp. 111-12), one can say that he left Horndolde 18 or 19 July. Faidherbe was surprised to find Umar at Horndolde and even more surprised that the Shaikh then went west rather than east, but he did nothing during his stay at Matam to pursue his arch enemy. Annales sénégalaises, pp. 163-6; ANS 13G 140, piece 27 (Matam, 2 Aug. 1858, Capt. Ravel to Governor).

45. ANS ID 13, passim. Faidherbe used the information from the observation garrisons to exaggerate the degree of Umarian threat in Cayor and thereby obtain increased support for his planned Cayorian expedition from the MMC. Bâ, Pénétration, pp. 146 ff.; Barrows, “General Faidherbe”, pp. 569-70.

46. ANS 13G 23, piece 6 (2 Sept. 1858, Faidherbe to the Governor par interim, Robin, at time of departure).

47. ANF, OM SEN I 45 (Paris, 14 Oct. 1858, Faidherbe's “Mémoire sur la colonie du Sénégal”). It is reprinted in Bâ, Pénétration, pp. 130-8.

48. On the Madiyu, see Robinson, Chiefs and Clerics, pp. 83-4. The Madiyu's letters to the French are found in ANS 13G 136 and 140.

49. Interim Governor Robin wrote to Mamadu Biran on 25 Nov. to say that he would not act until the situation was clear and that Mamadu should do nothing to disturb Umar at Hore-Fonde (ANS 3B 96).

50. Umar apparently had about 2,000 persons in his procession as he left Bundu (Annales sénégalaises, p. 162), but many of these accompanied the convoy which left Horndolde for Nioro. French sources give 400 to 500 for Hore-Fonde in October (MSD of 26 Oct. 1858) and 1,500 to 1,600 for Njum in Toro in January (ANS 13G 120, piece 114, 19 Jan. 1859, Commandant to Governor).

51. Interviews with Hamady Sayande N'Diaye at Seno Palel on 14 Feb. 1974 and with Samba Bokar Seck at Semme on 24 Apr. 1968.

52. Kamara, Zuhuur, II, fo. 11.

53. Communication from Oumar Kane, History Department, University of Dakar, 26 Jan. 1974.

54. Robinson, Chiefs and Clerics, pp. 43-61, 124-59, 203.

55. ANS 13G 157, piece 39 (Matam, 25 Dec. 1858, Holle to the Directeur des Affaires Politiques); Kamara, Zuhuur, II, fos. 30, 40-1.

56. Segu 3/Cam, pp. 113- 14.

57. Many of these stories emerge in my interview with Cerno Muntaga Tal at Dakar on 22 Feb. 1968 and in Muntaga's biography of Umar.

58. I have here combined elements from two interviews with a maabo informant, Hamady Sayande N'Diaye: one at Kanel on 25 Apr. 1968 and one at Seno Palel on 14 Feb. 1974. The incident to which the interviews correspond can be dated to late September from a communication of Paul Holle, who said that a cleric named Falil had died of wounds which Umar had someone administer (ANS 13G 157, piece 35, 1 Oct. 1858, Commandant to Governor). Kamara records that Falil Talla, a pupil of Sidiyya, was beaten to death by Futanke supporters of Umar ( Tanqiiyat); the Talla lineage is one to which the informant N'Diaye is closely attached. Similar criticisms were made of Hausa society by Uthman, especially in his Nasaa'ih al-Ummat al-Muhammadyya. See F. H. El Masri, ed. and trans., Bayaan wujuu-b al-hijra of Uthman b. Fudi (1978), pp. 7, 14, 19; and M. Hiskett, “Reform”, pp. 587-8. The informant may be recalling oral or written criticisms by Umar which drew from the same sources as Uthman, or indeed Umar might have adapted his version from Uthman's.

59. Bokar Sada intercepted the convoy and killed many of its members in December 1858. MSD of 11 Jan. 1859.

60. On the basis of context I have assigned this poem to 1858-9. Extracts from it are found in Kamara, Zuhuur, II, fo. 296. A French translation may be found in Samb, “Omar par Kamara”, p. 794. For Umar's time in Toro, the most complete source consists of the letters of the Podor Commander in ANS 13G 120. He was often badly informed, however. The claims that Umar burned Halwar and other villages appears in the MSD of 15 and 18 Feb. 1859. While they may be false, the Shaikh did apply enormous pressure.

61. Interview with Muntaga Tal cited in note 57. 62. Famine began in Toro in February. ANS 13G 120, piece 118 (7 Feb. 1859, Commandant to Governor); 140, piece 21 (7 Dec. 1858, Chief Butuneya of Podor to Governor); MSD of 1-3 Mar. 1858 and 8 Mar. 1858.

63. Faidherbe returned on 12 Feb. The gunboat Bourrasque went up to Podor in mid-February and the Governor himself went there on 23 Feb. MSD of 15 Feb. and 1-3 Mar. 1859.

64. Despite the surveillance, Mamadu Biran managed to communicate regularly with the French and spirit some of his considerable holdings in slaves to Matam and St Louis for safe-keeping. ANS 13G 140, piece 40 (Aug. 1860), and 13G 169, piece 14 (19 Apr. 1864).

65. ANS 13G 120, piece 120 (19 Mar. 1859); MSD of 8 Mar. 1859; Kamara, Zuhuur, II, fo. 102.

66. For the battles, which occurred in Tomora east of Khasso, see ANS 15G 108, piece 81 (extract from Medine letter of 7 Apr. 1859); Annales sénégalaises, pp. 170-1; Rancon, p. 532; Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali, pp. 8, 12.

67. ANS 13G 157, piece 48 (17 Apr. 1859); Soh, Chroniques, pp. 79-80; Segu 3/Cam, pp. 119-20.

68. See note 32, above; Robinson, Chiefs and Clerics, pp. 56-62.

69. Umar continued to exert pressure on Futanke after returning to Nioro. See his letter to some Denyanke and Yalalbe leaders of eastern Futa in BNP, MO, FA 5721, fo. 93.

70. For Arondu see Annales sénégalaises, pp. 173-4. There is some ambiguity about Umar's principle both in the internal and external sources. Segu 3/Cam (pp. 109, 121-2) claims that Umar gave an order to attack the Senudebu fort, an order which was never carried out if given, and that he ordered an attack at Matam on “those who were with” the Europeans. The Matam claim is compatible with what actually happened, namely a skirmish between the caravan and the inhabitants of the village. See also Annales sénégalaises, pp. 172-3; Barrows, “General Faidherbe”, pp. 389-90; Samb, “Omar par Kamara”, p. 803.

71. This figure is cited by Mage both in his report in the archives (ANS IG 32, piece 35, page 32) and in his book (Voyage, p. 160). Soleillet (Voyage, p. 344) repeats the 40,000 figure. Faidherbe, however, gives a figure of only 10,000 to 15,000 (Annales sénégalaises, p. 173).

72. ANS 15G 108, piece 73 (7 Oct. 1858); Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali, p. 11; Blanc, “Notes”, p. 96. The Segu support probably marks the accession of Bina Ali, who would be Umar's enemy, to the throne of the Bambara kingdom. See chapter 7.

73. Reported in ANS 15G 108, piece 75 (13 Oct. 1858, Commandant to Governor), as Jibi's response to Alfa Umar Baila.

74. On these arrangements, see Robinson, Chiefs and Clerics, pp. 51-3. Paul Holle was brought in to run Salde in 1861-2. ANS 13G 147.

75. The most complete account is Th. Aube, “Trois mois de campagne au Senegal”, RDM, I Feb. 1863. See also Annales sénégalaises, pp. 175-86; Barrows, “General Faidherbe”, pp. 247-9; Kamara, Zubur, I, fos. 159-61. Kamara in another work (Amar Samb, trans., “Condamnation de la guerre sainte”, BIFAN, B, 1976, pp. 170-1) recalls, on the basis of extant traditions in eastern Futa in the early twentieth century, the cruel executions and punishments ordered by Sire Adama, Umar's nephew, at Gemu. Those actions reflect, in part, the highly charged and polarized atmosphere of the late 1850s.

76. Aube's figures (pp. 547-9) are preferable to Faidherbe's of 136 dead and wounded. Aube was actually present and he took charge after his commanding officer was wounded, while the Governor was inclined to play down the figures to avoid the wrath of Paris. In October and November the French also destroyed Komendao and Melga, two other Umarian centres in Gidimaka.

77. On the movement to Gambia and Casamance, see ANS 13G 364, piece 21 (14 July 1859, Commandant Sedhiou to Governor). On the chaos in eastern Futa, see Kamara, Zubur, I, fos. 220-1, 342, and II, fo. 46. For the impact on Khasso, see S. Cissoko, “La guerre sainte umarienne dans le Khasso”, in R. Mauny Festschrift, Sol, Parole, Ecrit, vol. 2, pp. 717-21. For general impressions in March and April 1860, see J. E. Braouzec, “L'hydrographie du Sénégal”, RMC 1861, pp. 101-14.

78. Rançon, “Le Boundou”, 530. Demba Sambalou Seck (Curtin interview of 3 Mar. 1966) reports that there was no farming in Bundu for two years.

79. ANS 13G 177 (20 June 1862, Commandant Bakel to President of the Imperial Court). See Cissoko “Guerre sainte”, pp. 718-21, for widespread pawning in Khasso.

80. ANS 13G 250, pieces 6, 8-9.

81. Total exports from Senegal over these years were as follows, rounded to the nearest thousand francs:

| 1853 | 5,548,000 | 1857 |

3,173,000

|

| 1854 | 3,838,000 | 1858 | 5,067,000 |

| 1855 | 3,226,000 | 1859 | 4,005,000 |

| 1856 | 3,533,000 |

The French attributed the difficulties in most of the years save 1858 to Umar. RAC 2 (1860), pp. 94-6.

82. See the Vincent reference in note 29 above.

83. The fullest account of the negotiations, including a copy of the draft treaty, is found in St Martin, Relations diplomatiques, pp. 91-110. See also Kanya-Forstner, Conquest, pp. 41-2; Mage, Voyage, pp. 28-9, 273-4.