Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1985. 420 pages

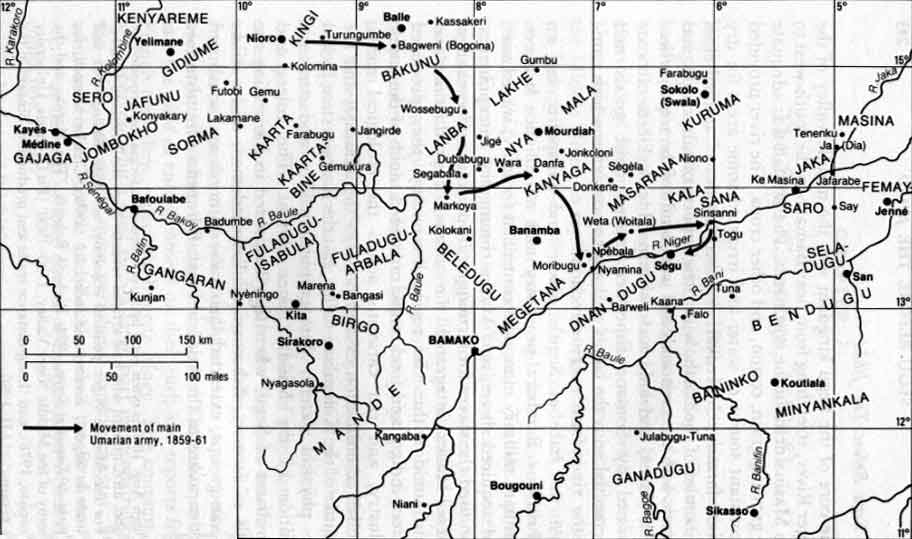

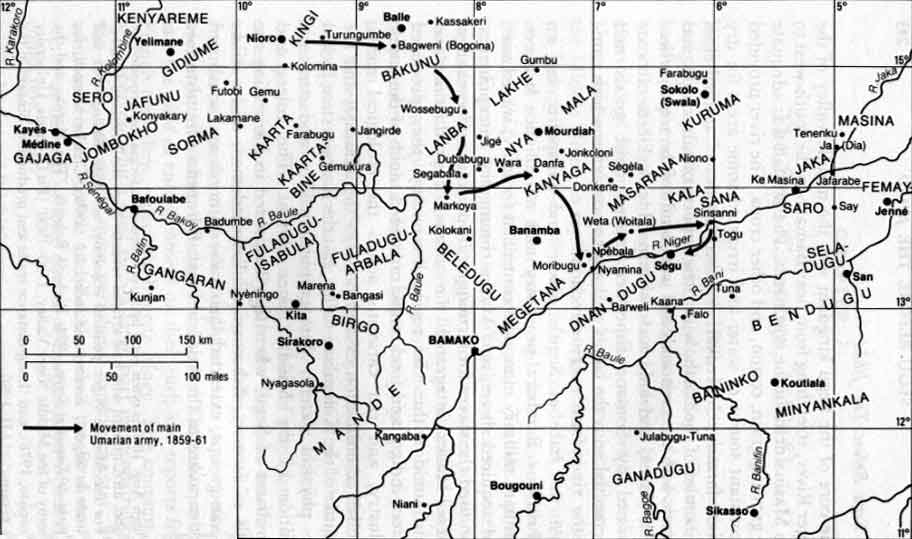

Well before the negotiations of 1860, Umar launched his campaign against the Bambara kingdom of Segu. The assault had been previewed for a long time, for the jihaad had always been directed against 'pagan Bambara' powers. It was in the aftermath of Medine that specific plans were set in motion. Umar now needed a new agricultural and commercial base on the Middle Niger, to replace the Senegambian sphere which the French had pre-empted. He had succeeded in recruiting on a vast scale, but he must now provide his recruits with the fruits of jihaad. The obstacles were gigantic. To take a poorly trained, poorly integrated army 400 kilometres to the east, well beyond its logistical support, to encounter a military machine which had maintained a fearsome reputation for 100 years—this required a scale of commitment, ambition, and desperation which make the Karta campaign pale by comparison.

The key position of Segu in the jihaad and in Amadu Sheku's subsequent reign makes for an abundance of detail in the internal accounts. The narratives fairly tremble with fear and anticipation at the assault on the “citadel of paganism”. The external traditions are equally rich: the Bambara traditions which praise the heroism of armies in defeat; accounts from commercial communities who sought to adapt to new political overlords; views from Muslim Masina and Timbuktu, which saw the jihaad as encroachment on their turf; and reports from French travellers, especially Eugene Mage. The contemporary archives, which play such a large part in reconstructing the 1850s, are much more peripheral to this chapter. The commanders at Medine and Bakel worked too far from the scene, at the end of long chains of transmission which they could not verify 1.

The core of the Segu kingdom was the middle valley of the Niger River, stretching from near Bamako in the south-west to the Masina delta in the north-east. The rainfall was adequate for growing grain, cotton, and other crops. The river provided a constant source of water and irrigated some areas for dry season farming. Moreover, it linked the desert and sahelian economies of the north, with their exports of salt, cattle, and horses, with the savannah and woodlands of the south, where gold, slaves, and kola nuts were produced. Fleets of boats manned by Somono fishermen moved these goods and intersected with the camel and donkey caravans which came to the river from every direction 2.

At the base of Segu's power and prosperity lay an industrious Bambara peasantry and an alliance between Bambara military men, who controlled territory, waged war, and acquired slaves, and Marka commercial entrepreneurs, who used the slaves for farming, transporting, and exchange. These Marka integrated the means of production and distribution within the regional economy; they produced cotton, indigo, and food crops, organized much of the textile industry, and ran caravans across the ecological zones. Similar co-ordination existed between the Massassi and the Soninke of the Kolombine valley, but the Karta system lacked the physical extent, demographic density and strategic position of the Middle Niger variant. The rulers and merchants of Segu, when they succeeded in harnessing the skills of farmers, fishermen, Fulbe cattlemen, and various artisan groups, extended their sway to north and south and sent caravans to the Atlantic coast. European administrators along the coast testify to Segu's reputation for wealth and power in the early nineteenth century 3.

Map 7.1 — The Middle Niger; adapted from C. Monteil, Les Bambara du Ségou et du Kaarta, 1977

The key social institution among the Bambara was, as in Karta, the tonjon or association of “submitted” persons who constituted the army and much of the bureaucracy. These men, originally captured in war, were incorporated into regiments stationed at key locations in the middle valley. By dint of loyal service and military heroism, they might acquire considerable influence. Some acceded in time to the post of regimental commander, which meant active participation in the highest councils of the state, where the succession to the throne was decided. In the nineteenth century that throne was filled by descendants of one such commander who had usurped the position of the founding lineage. This Jarra dynasty had consolidated its control of the heartland and periphery under three kings or Famas of great imagination and military acumen 4. They created a tier of subordinate provinces which exchanged tribute for some protection and internal autonomy. Beyond this range, and particularly to the south and west, they conducted raids for cattle, grain and slaves.

Many of the slaves were fed into the two principal hubs of Middle Niger commerce, the Marka centres of Nyamina and Sinsani 5. Nyamina was oriented to trade with the south and west. Sinsani lay north of Segu and specialized in trade with the desert and Sahel. In both areas slaves were used for local farming, weaving, or transport, or they might be sold into the internal or trans-Saharan trade. They became part of a highly integrated system managed by the Marka under the watchful eye of the state.

The warriors and merchants spoke the same language, the Bambara dialect of Mandinka. But their vocational specializations correlated with contrasting religious affiliations. The Marka practised Islam through their Koranic schools, mosques, and judges. They were not especially learned or pious by Umarian standards, but they were identified as Muslim in the local religious and ethnic canon. The ruling class, on the other hand, practised rituals associated with traditions of farming, hunting, and war. The king played a leading role in religious ceremonies attached to the annual productive cycle. Like his counterpart in Karta, he maintained temples and priests at court and in important villages. Segu religion was a system of practices and beliefs nurtured by a professional clergy, over and above the diverse observances at the local level. It was not necessarily hostile to Muslim clerics—witness the ties of the Jarra kings to the Kunta of the Timbuktu area; but it attracted the criticism of Muslim reformers like Umar 6.

By the middle of the nineteenth century the kingdom had lost some of its lustre. In the 1820s its Masina tributary had broken away as the Caliphate of Hamdullahi. Hamdullahi diverted some of the northern trade and absorbed a great deal of Segovian energy in border skirmishes. At about the same time the Tamba state emerged in the Upper Niger and cut into Bambara tribute, trade, and booty in the south-west 7. Diminished success in warfare meant less reward and advancement for the tonjon. The resulting dissatisfaction found an outlet in the competition of factions for power in the capital. The tonjon organized behind various Jarra brothers, all sons of King Monzon and of approximately the same age. Together the sons and soldiers created a pattern of instability in sharp contrast to the long and prosperous reigns of an earlier day.

One contest between factions took on a heavy religious colouring associated with the Umarian jihaad. Torokoro Mari Jarra came to power about 1854. In 1856 he received the delegation which Umar dispatched to explain his reasons for the Jangirde garrison on Segovian territory 8. The king accepted the explanation and sent a Futanke long resident at his court, Cerno Abdul Aw, to communicate his friendly disposition towards the mujaahid. Cerno Abdul returned to Segu and then left again to join Umar in 1858 9.

At this point, according to Bambara tradition, the tonjon leaders joined with the king's brother to depose Torokoro Mari. They discovered, as they had suspected, that he was a closet Muslim, that he had shaved his head, used a wig, and substituted honey for beer at public ceremonies: “They came at night to arrest him. They told him: “ You have betrayed the country and the people. We made sacrifices to protect us from such things, but then you went and secretly converted. You have betrayed the country ” ” 10. The tonjon drowned the king in the river and installed his younger brother, Bina Ali, in his stead.

This widespread Bambara account demands close scrutiny. It is highly unlikely that a Segovian king would actually convert to Islam, given the long and careful socialization of members of the royal dynasty. Nor is conversion necessary to explain the assassination. Kege Mari Jarra, the principal royal conspirator, had long harboured grievances against his older brother, and the rivalries among tonjon factions were notorious 11. None the less, the persistence of the tradition in conjunction with the observations which Cerno Abdul communicated to Mage strongly support a hypothesis of tolerance towards the jihaad from 1856 to 1858, at a time when the fighting largely involved Karta and eastern Senegambia. This tolerance could not have come at a more welcome and vulnerable moment for the Umarians.

By about September of 1858 the good relations were over. Bina Ali acceded to power, stoked up the embers of Karunka Jawara's revolt, and put the beleaguered jihaadists in Nioro on the defensive. It was to secure Karta's defences once and for all, as well as to achieve the larger goal of a new base on the Middle Niger, that Umar embarked on the Segu campaign in 1859 12.

In September 1859 Umar left Nioro for the Middle Niger. In September 1860 he conquered the main Segovian forces at Woitala in a battle which reverberated through the Western Sudan and constituted the climax of the “jihaad against paganism”. For the intervening year the internal narratives overflow with intense rhetoric: the bold brave disciples, under their blameless leader, sally forth against the hordes of unbelievers, the asses of filth, the armies of Satan. The mujaahid performs miracles: he provides water in the dry season and dries up mud in the wet season. He constantly exhorts his men, reminding them of the promise of Paradise and extracting their last ounce of commitment 13.

The intensity of language has a rough proportion to the size of the task facing the jihaadists. Umar wanted to move some 25,000 soldiers, and perhaps 10,000 women and children, to wage a sustained campaign hundreds of kilometres from his main theatre of operations. He would face a sturdy if slightly tarnished military machine with an army dominated by inexperienced recruits. Many of them had been coerced into emigrating and some succeeded in deserting in 1859-60 14. The entire army had not fought a coordinated campaign after the invasion of Karta in 1855. Since that time individual units had been operating out of Dingiray, Kunjan, Konyakary, Jangirde, and the other garrison towns. All these forces would have to work in tandem to defeat Segu.

Umar did possess one distinct advantage the superiority in weapons which he had consistently maintained against his more landlocked foes. He now had two howitzers and four small cannon captured from the French 15, a host of double-barreled muskets, and imported powder. He had retrieved cannon-balls and shells at Medine and stolen shells and cannon charge at Bakel in 1859. He prepared camel teams to haul the artillery, carpenters to repair the carriages and smiths to mould additional balls. He knew that his cannon might play the critical role against the mud walls of the Middle Niger, and he put them in the hands of his man of all trades, Samba Njay Bacily 16. Umar also provided authorization for his representatives to pursue negotiations with Faidherbe. By the summer of 1860 these negotiations had probably eased the official arms embargo, and they certainly diminished the military threat against the garrisons in Konyakary and Kunjan 17.

Umar had been preparing for the Segu campaign since 1857. During his convalescence at Kunjan he dispatched a contingent of 1,500 men, out of his reduced force of 7,000, to establish a dominant position between the Upper Senegal and Middle Niger valleys 18. Alfa Uthman So, a brilliant soldier with little Islamic education, led a regiment of soldiers primarily from Fuuta-Jalon. For the small Mandinka villages and chiefdoms in the Bafing and Bakhoy watersheds, the Umarian force resembled the raiders from Segu, Karta and Tamba that they had long endured. As part of the West African “Middle Belt” of vulnerable societies, they took refuge on the mesas above the valley, or in the lands to the south, leaving behind their grain, cattle, and some of their weaker members. But in their traditions they did pay special tribute to the thoroughness of the Umarian invaders. They labelled the leader “Alfa of the White Hand”, in memory of the lightly coloured Fula fist which brandished the sword. And they remembered their own distress: “The war endured throughout the rainy season. There were no more huts, people lived in caves. That is why there are so many Birgo slaves among the Bambara: people were sold to get rice 19”.

By the end of 1858 the Fuuta Jalonke regiment had completed most of its task. All Mandinka resistance had been suppressed. The connections with Bure and its supplies of gold were re-established. The trade route from the coast via Timbo and Dingiray could now stretch into the underbelly of Segu 20. Alfa Uthman crowned his success by building the fortress of Murgula in the Bakhoy valley, on the main route from Nioro to Bure. The walls provided protection from Segu and could contain substantial supplies of cattle, grain and slaves 21.

Attacks did come from Segu and its ally in Bangassi, the capital of Fuladugu which lay north of Murgula and blocked access to the Middle Niger. Bangassi enjoyed substantial autonomy under the overrule of Segu, and now called upon the new regime of Bina Ali for support. With Bambara help it resisted two attacks from Alfa Uthman and retaliated with raids against Murgula. In November 1859 the fortunes were reversed. The Fuuta-Jalon regiment, taking advantage of the departure of the Bangassi leader for Segu, stormed the capital fortress and razed it to the ground. More than any other achievement of the Mandinka campaign, the victory against Fuladugu made the reputation of Alfa Uthman. His unit became the “arm of Murgula” within the jihaadic army 22.

More difficult to resolve than the problem of fire-power or the Mandinka corridor was the issue of Umarian unity. One cleavage ran across geographic lines—the division between the Fuuta-Jalon followers, dominant in an earlier day, and the Senegambian majority. It threatened to divide the force when Umar reintegrated the regiment of Alfa Uthman into the larger army. The other division ran through the sons of Umar, their mothers and partisans in Dingiray; it was especially deep between the two oldest sons and potential heirs, Ahmad al-Madani and Muhammad al-Makki, both born in Sokoto about 1836 23. Umar was now over 60 years old. As he undertook a campaign of such high risk, he could hardly avoid any longer the question of succession.

The mujaahid was acutely aware of both dangers to the integrity of his mission. He chose to confront them in the charged, unifying atmosphere of the jihaad against Segu. Accordingly, he sent messengers to Alfa Uthman and to the Dingiray community to fix a rendez-vous for late 1859 on the edge of the Middle Niger 24. He then set out from Nioro with the main force in September. The column moved slowly at first to allow patrols to stamp out the last flames of another Jawara revolt. After the millet harvest in October it moved more swiftly and, by late November, invaded Beledugu, a Bambara society which fell under Fama Ali's overall jurisdiction and had served as the headquarters for the Jawara. The Umarians used their howitzers to demoralize the inhabitants of Markoya, the principal fortress, and made it their staging centre for the next four months 25. The victory, together with the triumph at Bangassi, marked the first salvo in the holy war against Segu.

Amadu and Makki, as the oldest sons were commonly called, together with Dingiray's small force, were by now making their way through the Mandinka corridor. They numbered something over a thousand. In Fuladugu they linked up with Alfa Uthman and his regiment, of approximately similar size, and celebrated the success at Bangassi. The two groups shared close ties of kinship, origin and experience, and both looked to Dingiray and Fuuta-Jalon, rather than to Nioro and Senegambia, as their home 26. By late December they had marched into Markoya.

It is at this point that the Dingiray chronicle provides insight into the divisions between the two constituencies. Umar organized a parade on behalf of Alfa Uthman and his victorious regiment. When the Senegambian troops expressed their resentment, the Shaikh changed his mind and punished the regiment by taking away some of the booty and harem acquired over the last two years. An angry Alfa Uthman slipped into the Markoya arsenal, took a supply of arms and escaped with a handful of men to Murgula. The Shaikh then called upon his leading disciple from Fuuta Toro, Alfa Umar Baila Wan, to bring Uthman back. The chronicle recounts the conversation at Murgula between the two leaders:

Alfa Umar:

— The shaikh has sent me for you.

Alfa Uthman:

— I will not go! …

Alfa Umar then began to preach to him, flattering him to make him calm down. When he had become calm he answered Alfa Umar asked:

— Will you tie my hands and feet and give me to a snake?

Alfa Umar:

— I will never do that!

Alfa Uthman:

— I fear that treachery lurks behind your word.

Alfa Umar:

— I swear to God I will never do that… I and those with me are from [Fuuta] Toro, we have forsaken home, wives, slaves, relatives, cattle, wealth, people and country to follow the Shaikh into strange lands and troubled times, for the sake of religion. So have Ɓundu and you from Fuuta Jalonke. You have left your families and possessions. We have all abandoned everything and counted it as lost, all for the sake of religion. Now I pray you, for the sake of God and His Prophet, do not forsake religion…

[The two men came out of their conversation] with tears in their eyes. They went to al-hajj [Umar] and [Alfa Uthman] asked for forgiveness 27.

The “forgiveness” was in fact a compromise whereby the “arm of Murgula” remained intact and retained much of its booty. It was perhaps the most effective single unit of the army.

The succession question was harder to resolve. Amadu and Makki each had good claims to the uncharted inheritance of Umar and the jihaadic state. Both were of “noble Nigerian” birth, Amadu by a woman from near Sokoto, Makki by a woman from Bornu 28. Amadu was probably a bit older. Makki, on the other hand, had established a reputation for learning in the confines of Dingiray. He wrote a bit of poetry, built a library, and became a patron of scholars. When Abdullay Hausa brought booty from the Karta campaign in late 1855, for example, Makki had one of his teachers, Muhammad ibn Ibrahim of Labe, write a short commemorative poem 29. Makki was generous and flamboyant, Amadu cautious and parsimonious 30. In the isolated incubator of Dingiray, the ambitions and anxieties of these candidates and their respective partisans had free rein.

In late February 1860 the Shaikh declared clearly in favour of Amadu. In a short document called “the chronicle of the succession”, the same Muhammad ibn Ibrahim recounted the story of how Umar assembled the whole company of the jihaad:

The Shaikh took Ahmad al-Kabir and appointed him successor. He said to him:

“Everything given to me…, I give it all to you and permit you to give it. Anyone who seeks the wird of wirds [rituals of the Tijaniyya] from you, give it to him…”Then he said to the community:

“This is your Shaikh. Anyone for whom I am the Shaikh, this one is now his Shaikh. Seek from him all you wish in this life and the next.”

They consented.

…Those present swore allegiance to Ahmad al-Kabir in the presence of the Shaikh, and the people followed suit in swearing their allegiance to the Commander of the Faithful, Ahmad al-Kabir al-Madani al-Tijani of Fuuta Toro and Gede. That was Sunday, before noon, the 26th of Rajab 1276 [19 February 1860]. The people swore allegiance, including the leaders of the army… 31The Shaikh also gave recognition to Makki: he would possess all of the secrets and favours promised in Rimah. This was probably a reference to a privileged role within the Tijaniyya. But there was no debate about Makki's subordination:

“You and all of yours, obey your brother …. Do not let divisions come between you” 32.

For the moment, the succession matter was resolved. Amadu and Makki and Umar's nephew Tijani were integrated into the armed forces to gain military experience. Amadu began to handle some administrative chores and questions of affiliation to the Tijaniyya.

One other question threatened the unity of the Umarians at Markoya: the disposition of the women and children who had accompanied the convoy. Some were the families or relatives of talibe, others were slaves acquired in previous campaigns. As the dry season grew hotter and food supplies ran short, the Shaikh realized his mistake in bringing the dependants along. Since he could not afford to protect and supply them in the difficult months ahead, he ordered them to return to the west under a light escort. The protest within the ranks was deafening, but the command was carried out. Some women refused to return: they followed the army and were captured by Bambara bands. Most did return, and many of them became casualties of the hungry season. The march back is remembered in the Upper Senegal as the “famine of Markoya”, and Mage, stationed at Makhana in 1860, witnessed its effects:

« [I saw] bands of individuals, where women and children formed the predominant part, veritable walking skeletons who had not for a month or even more eaten anything other than leaves and grass. 33»

These exhausted bands, the misery of the Mandinka corridor, and the collapse of the Senegambian economy: all were part of a crescendo of disaster afflicting the whole arena of jihaad.

After the unpopular and brutal decision to send the dependants back, the Shaikh prepared to march to the Niger against the main Bambara forces 34. With the incorporation of the Fuuta Jalonke regiment and the Dingiray soldiers, he could now deploy an army of about 25,000 organized into five regiments: four “legs” and one “arm” (see Table 2). Each unit was divided into an advance guard, main body and rear guard. Since Umar had greater confidence in recruits from Western Fuuta, pastoral Fulbe and companions from earlier days, he relied particularly on Toro, Jomfutung and Murgula. While he left the actual fighting to the regimental commanders, he planned the basic military strategy.

The march from Markoya to Nyamina fell in April and May 1860, at the height of the hot and hungry season. Umar led his forces to the north-east and then to the south-east to take advantage of grain stores and water; during this movement the internal narratives credit him with miracles of provisioning. It was a testing time which the Segu chronicler captures in a pithy verse:

“There they felt hungry and tired, there they had again to be patient, there beans were boiled to make porridge, which had no energy at all.” When the army burst through to Nyamina, the same chronicler records their delight at bathing in the Niger 35. During the march the Umarians won two major victories. The first came against a local Bambara capital, where again the French cannon shells burst inside the walls of the tata. The more important triumph occurred at Ngano, where Umar used surprise and manoeuvre to defeat the first major force sent by Bina Ali. In both encounters he captured a large number of mounts for his cavalry 36. The Shaikh also accepted the submission of a cluster of Marka towns. While these merchant families were sensitive to their religious links to the jihaad, they were much more impressed by Umarian military might and hoped to maintain their privileged position in any new political economy which might emerge 37. Their submission set the precedent for most of the Marka in the larger towns of Nyamina and Sinsani.

The mujaahid spent the months of June, July, and August in Nyamina. He was able to rest the troops, stock up on weapons and food, and consolidate a measure of control in the conquered areas. The Mandinka corridor enabled the Umarians to bring in arms from Sierra Leone, while their position on the river enabled them to cut off similar supply routes to the capital. The Shaikh used the time to plot his strategy against the Segovian military. He knew that the main battles lay ahead. He would move carefully to consolidate his rear flanks and supply lanes. He counted on his cannon in siege warfare, his cavalry in the open field, and the over-confidence of the Jarra dynasty. He was determined not to split his forces, as he had done to bad effect in Karta, but to concentrate on each battle until he routed all of the enemy. Then, and only then, would he worry about administration and the deployment of garrisons 38.

Table 7.2 — The Umarian Army in 1860a

| Unit | Title | Composition |

| Leg1 | Ngenar | Yirlaaɓe, Hebiabe and Law in Fuuta Toro. Volunteers from Khasso, Jafunu, and Bakhunu. Some talibe from Fuuta-Jalon. Leader: Alfa Umar Baila Wan from Fuuta Toro. Flag: black. |

| Leg 2 | Yirlaaɓe | Toro, other areas of western Fuuta Toro, and Ɓundu. Volunteers from Gidimaka. Leader: probably Cerno Alassan Ba of Toro. Flag: red and white. |

| Leg 3 | Toro | Recruits from Ngenar, Bossea, and Worgo in Fuuta Toro; volunteers from Jawara, Massassi, and Kagoro areas of Karta. Leader: probably Umar Cerno Molle Ly of Fuuta Toro (Thilogne in Bossea) Flag: white |

| Leg 4 | Jomfutung | Pastoral Fulbe of Fuuta Toro; Hausa free men and slaves; tuburus (groups that voluntarily submitted). Leader: not clear. Flag: red. |

| Arm | Murgula | Force that had served at Murgula; other talibe from Fuuta-Jalon. Leader: Alfa Uthman So of Fuuta-Jalon. No flag. |

Nyamina served as the base for sorties against the ever resourceful Karunka. The Umarians surprised their foe, decapitated him, and took many prisoners 39. Somewhat later they marched against the garrison of Jabal, breached its walls and killed a large number of tonjon. They revelled in the booty, 600 women and 500 horses of fine quality, but the Shaikh warned them that the real confrontation was yet to come: “You have been playing up till now, you have not yet been at war. The sons of the chiefs have not yet come, the wealthy of Segu have not yet given you a thought.” 40

The “real” confrontation came between 5 and 9 September in the plains of Woitala, a garrison town a few kilometres in from the left bank. Woitala is the best known and perhaps single most important battle of the entire jihaad, and it is consequently wrapped in shrouds of Umarian and Bambara tradition. Underneath these layers one can see an army of about 25,000 jihaadists, swollen with local recruits from the Nyamina period, confronting about 35,000 Segovian soldiers under the command of Tata, oldest son and potential successor to Ali. The Bambara enjoyed the advantage of walls. The Umarians hoped to counter with their fire-power. In preparation the two sides traded taunts. Umar, according to the internal narratives, spent his time in prayer and exhortation. According to the Bambara versions, he mobilized the spirits under the earth and hung like a bat from a tree, counting his beads 41. The rhetoric and fantasy match the anxiety and anticipation: Woitala would decide the fate of the Segu campaign and the jihaad.

The first attack on the fortress was a disaster. Tata's tonjon poured a withering fire on the advancing columns, killing several hundred men from the Ngenar regiment and putting the rest to flight. Only one artillery round was fired, for the wheels of the carriages collapsed. The cannon were rescued only through the daring of Samba Njay. Umar, who had stayed behind during the initial charge, shouted at his fleeing troops: — “Where do you think you are going? Returning to Nioro? Do you not realize that you will die en route, by hunger or the attacks of Segu, who will not fail to pursue you? I am telling you, we must die here or conquer. 42”

With such arguments the Shaikh persuaded his men to rally and encircle the garrison at a distance. He occupied a small village of blacksmiths where he had the cannon and carriages repaired by Samba Njay. After four days the cannon were ready, along with ladders, to scale the walls. The jihaadists advanced in a disciplined array, shouting “God is helping us, let the pagans be destroyed.” This time the artillery shells sowed panic inside the walls, while the regiments stormed in and over the defences to complete the massacre. Tata and his entourage, in a fashion befitting the code of warriors and nobles, blew themselves up in the powder magazine. The toll was awesome for warfare in the Western Sudan: 3,000 Bambara killed, thousands taken prisoner, 500 horses captured. The Umarian toll was lighter but still significant, and the Shaikh ordered his men to rest in the Woitala plains 43.

The victory was decisive. The surviving tonjon leaders now affirmed their allegiance to Umar, as did the Somono fishermen who controlled the river. With this support Umar could easily have moved against the capital, more or less opposite Woitala on the right bank. Instead, and in keeping with his tactic of consolidating his victories, he stayed on the left bank and moved into Sinsani, the northern commercial entrepot of the Segovian kingdom. This move enabled him to refresh and resupply his troops, as he had done in Nyamina, and to secure the resources of this rich centre of production and distribution. According to the traditions, he impressed his new hosts with the number of his horses and by the gun barrels reflecting in the sun; in turn he was impressed by Sinsani's wealth in cloth and slaves. One year and one month after leaving Nioro Umar was the virtual master of the Middle Niger; he had found his new centre of gravity to the east 44.

Woitala shattered the lingering confidence of Bina Ali. After losing his son, relatives and tonjon by death and defection, the Fama took an unprecedented step: he swore allegiance to his traditional enemy in Masina 45. The Caliphate of Hamdullahi had fought intermittently with Segu for several decades. In the 1850s Amadu III pressed the struggle against the Bambara much more consistently, sending armies against the Segovian frontier every year. In 1860 Amadu and Ali abruptly transformed this enduring hostility into an alliance designed to avert the conquest of Segu and undercut the ideological basis of the jihaad. In exchange for Hamdullahi's protection Ali agreed to pay a tribute and make some effort to establish Islam in the state. Several mosques were constructed in the garrison towns which Ali still controlled. Some Masinanke scholars came to provide instruction and oversee the destruction of idols, shaving of heads, and banning of alcohol 46.

The Umarian threat was obviously the principal impetus of this invention. Another important moving force was Ahmad al-Bekkay, who watched in growing alarm the approach of the Futanke forces. At some point in late 1860 he wrote letters to Amadu III and Ali, urging them to resist the jihaad by every means at their disposal. The letter to Ali, discovered at a later date by Umar, was particularly incriminating in the literary and ideological debates waged by scholars, for it showed the Kunta leader apparently siding with “pagans” against the “army of God”. According to the Umarian version, it read:

« Ali, you must understand that I have a serious problem, for you and your people are pagans while your enemy is Muslim. I worry about the consequences of supporting you, and yet if I do not support you there will be a more terrible crisis. The purpose of my support is to protect you, preserve you and defend you, and to ask God not to abandon you… Ali, I will help you by all means available to me…, so that your rule will remain throughout your lifetime in Segu 47. »

In the midst of these arrangement Amadu III wrote to Umar at Sinsani to state his position: Segu was Muslim and vassal to Masina, and the mujaahid should consequently desist and abandon the Middle Niger. The date was approximately November 1860, and the key passage in the letter went as follows:

« It has come to our attention that you entered Sinsani without our knowledge or permission. We are displeased, especially since you are highly considered for your wisdom… Know that we have fought against Segu ever since the days of Shaikh Ahmad Lobbo, and we have consistently defeated them, killed their elders and chiefs, broken their power, debased them, made their women and sons slaves. Their realm has fallen into ruin and decline until now, when they converted to true religion and came under our obedience 48. »

The exaggerated claims were designed to intimidate Umar. They had the opposite effect.

The dramatic intervention of Hamdullahi profoundly changed the military and ideological equation. Masina troops might restore the balance of power that existed before Woitala; their cavalry were reputedly invincible. And since they were obviously Muslim, and part of an Islamic state organized on the same basis as the Futas and Sokoto, their intrusion skewed the sharp line between “pagan” and Muslim which Umar had carefully followed and effectively used in his propaganda. The “jihaad against the pagans” was over, or might soon be over, if Futanke fell to fighting Masinanke, and it would be no small matter to justify such a combat. It is precisely at this controversial moment that the Arabic documentation becomes abundant. While the debates over Muslim and non-Muslim identity were conducted by a relatively few scholars, the issues were of great import to all 49.

The Shaikh obviously had no intention of yielding to Amadu's demands, but he did wish to avoid confrontation as long as possible. He sent a prestigious delegation to Hamdullahi to appeal to the governing council over the head of the Caliph. The envoys, according to griot tradition, included an expert horseman, expert marksman, a praise-singer gifted in genealogy and song, a reciter of the Koran, and a scholar able to read and comment upon one of Umar's long poems 50. They were meant to impress their audience with the power and erudition of the jihaad. They communicated Umar's response, which began on a frosty note:

You claim that the people of Sinsani had sworn allegiance and are your subjects. This is a lie. This is a pure fabrication by the writer of the message. Three times they [the inhabitants of Sinsani] have informed us that their allegiance has been given to us, that they are our subjects, and that they prohibited your entry when you tried to come in….

It is clear that the writer lies from beginning to end. All ye faithful Muslims, judge between me and this lying writer… Do you consider that the passage of the Masina army through Karta made that region ours? Did it facilitate our conquest of Jangunte?… of Bassaga, the city of infidelity? Did you fight these cities until you broke their spirit and destroyed their energies?… Tell me about Markoya, city of idols…The catalogue of victories won by the jihaad continued. Ali had not converted; his payment was not a gift nor an expression of obedience, but rather a purchase of protection. Then Umar became more conciliatory:

“Oh company of sincere, faithful and loyal Muslims, what has come between us should be treated in accordance with the Law. We should be friendly, merciful, brotherly and free from hatred. You are Muslim and we are Muslim. We are all commanded to wage jihaad against the polytheists and the unjust. [We must] banish all disputes, competition and underhandedness among Muslims.”Finally, the Shaikh concluded with a condescending affirmation of the bond between him and the Caliph:

“As for Ahmad ibn Ahmad, he is our grandchild, the son of our son. His grandfather was our friend. We shall never be his enemy. We shall neither hate him nor love those who hate him. If anyone wages war on him we shall wage war on that person according to our ability. We love him totally and sincerely.” 51

Amadu and his council deliberated over the desired response and opted for war. By the end of December 1860 an army of about 15,000 cavalry and infantry arrived opposite Sinsani, on the right bank, and joined Ali's remaining troops. At the same time a terse ultimatum reached the Shaikh: swear allegiance to Amadu III, evacuate the Middle Niger or fight 52. The fearful and forbidden confrontation of Muslim with Muslim was now as close as the width of the Niger. For two months the soldiers chafed in their camps and hurled insults across the water. Neither side wanted to launch the battle or bear responsibility for attacking the “forces of Islam” 53.

With armies and pride so fully engaged, with no remaining base for mediation, it took little to ignite the conflagration. The spark came in late February 1860, when some talibe took isolated shots from the right bank as the signal of an attack. They crossed the river before Umar could call them back and were quickly eliminated by the Masina cavalry. The mujaahid knew that he could restrain his men no longer, and gave the order the next day to cross the river in two separate places, in the same pincer movement he had used so effectively at Kholu in 1855. The surprise manoeuvre, coupled with the cannon and guns, won the day at the village of Tio 54. The Masinanke fled to the north-east, the Bambara to the south-west, and the way to the capital lay open.

In early March the victorious army swept by the once legendary garrisons. On 9 March 1861, as a confused Ali fled in haste, the Umarians entered the “city of paganism” and the king's palace. The Segu chronicler described it as a march against the “stinking bastards who will never be clean” 55. The Dingiray chronicler allows his imagination to dwell on the wealth of the dynasty and the awe of the conquerors:

When the Shaikh came to his [Ali's] private chambers, he found his [uneaten] food. The bowl was made of gold, the soap dish was gold, the wash basin was gold, the carpet was of woven gold, his walking stick was gold, … even his bed was made from gold … The Shaikh entered the store house and found it partitioned into various apartments. In one apartment he found black shirts only, in another light blue shirts, in another black country cloths only …. He found stores of gold of such an amount that no one had ever counted its value… 56

The echoes of the triumphal entry went far and wide. A Paris travel journal, Tour du Monde, declared that Umar had defeated the “most energetic centre of resistance which idolatrous fetishism had yet opposed to Islam in the Western Sudan” 57. A Tijaniyya leader from Morocco put it no less vividly: “The capture of Segu marked the end of paganism, when the light of Islam shone with the brightest sparkle. The heart of every Muslim was filled with joy while that of every pagan became prey to fear and despair 58.”

The campaign in the Middle Niger was the height of the “jihaad against paganism”. The entrance into the capital was a cause of rejoicing in many Muslim circles. It was obvious that Segu, by its strategic location in the new centre of gravity of the Umarian conquests, would replace Dingiray and Nioro as the principal centre. Before this could happen, however, the jihaadists had to consolidate their military and political control. Indeed, they initially had to stave off a strong counter-attack. Less than a month after the triumphal entry, an army of 30,000 cavalry and infantry, mainly from Masina, advanced to the outskirts of Segu. After days of skirmishing Umar gave the order to attack and drove the foes from the field at Koghe 59. This time, unlike the battle of Tio, the pursuit was swift and ruthless. The jihaadists failed to capture Ali, but they took a heavy toll of the enemy and ended any immediate threat to the new state.

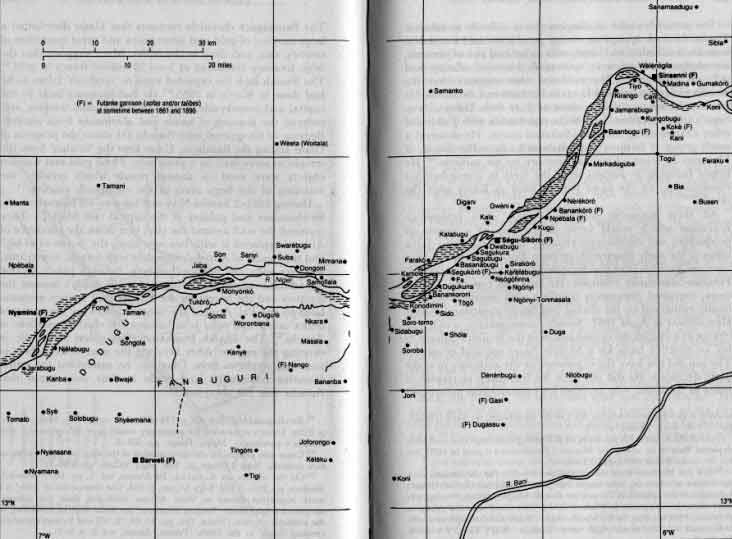

The Koghe victory brought new submissions. Many of the remaining tonjon troops surrendered and were incorporated into the growing sofa contingents of the army. The Jawara finally made their peace with Umar. The Somono of Nyamina and Segu, like their counterparts in Sinsani, performed their ferrying and fishing services for the new regime 60. Garrisons were placed in several locations on the right bank not far from the capital; together with the contingents which Umar had already left at Nyamina and Sinsani, they resembled the old deployment of the Jarra. Umar now had firm control of the capital, with a population of about 35,000, and the old Bambara heartland, with perhaps 200,000 inhabitants 61.

The enormous booty taken at the palace provided a means of rewarding loyal service and avoiding immediate taxation.

The Bandiagara chronicle recounts that Umar distributed a large number of gold and silver coins and great quantities of cowries, salt, and cloth to the talibe. Mage suggests that the Segu treasury contained at least 20 million francs in gold 62. The Shaikh took the expected steps to “establish” Islam as he had done in Karta in 1855 63. He had mosques built in the capital and countryside, destroyed the national temples, and ordered the shaving of heads and abstinence from alcohol. Because of his quarrel with Amadu III about the progress of Islam among the Bambara, Umar kept the “fetishes” from the temple to serve later as a proof text. These gold and wooden objects were used in annual rituals which recalled the founding of the Segu state in the eighteenth century 64.

During 1861-2 Samba Njay and his crew set to work on the fortifications and palaces of the capital (see Map 2). They repaired the wall around the city, tore down the residence of Ali and replaced it with two new ones, the “house of al-hajj” and the “house of Amadu”, complete with turrets, courtyards, audience halls, and private chambers. Amadu's palace became the administrative hub of the state, while al-hajj's became the treasury and the harem for the hundreds of women accumulated by the Tal. Around the two residences lay the homes of senior talibe and sofas who became the chief counsellors of Amadu 65. The Shaikh emphasized his oldest son's role in running the regime. After bringing the next oldest cohort of sons and nephews from Dingiray, he assembled the entire Umarian community and made it clear once again that Amadu was his successor 66.

Map 7.3 — Segu heartland and Futanke colonies

The actual transfer of allegiance was difficult to achieve. The talibe and sofas of an earlier generation had learned to look for leadership to Umar, who alone had the experience, knowledge, and vision to command this vast military and political enterprise. The evidence also suggests that the Shaikh himself continued to make fundamental decisions. He transferred the wealthy province of Bure from Dingiray's to Segu's administration 67. He encouraged trade with Tishit and other centres along the trans-Saharan routes. He obtained a small group of farmers and blacksmiths from the Sultan of Morocco to teach plough agriculture to his subjects 68. He began bringing in settlers from the west to strengthen his constituency, on the same pattern used in Karta after the revolts 69.

All these measures suggest a vision of a prosperous heartland which would serve as the hub of a system of production and distribution rivalling that of the great Jarra kings of the early nineteenth century. But Umar, as the year wore on, gave his attention increasingly to the burning issue of Futanke-Masinanke relations. He sent and received delegations, prepared documents bristling with justification, and finally embarked on the daring and fateful campaign against Hamdullahi in April 1862. Amadu, consequently, was left in charge and reaped the consequences of the Shaikh's failures to lay an effective basis for a Middle Niger political economy. The son did not have the experience or the authority to make basic decisions. He did not have the friendship or respect of many of the talibe, who resented his parsimonious nature and increasing reliance on sofa counsellors. Once the army left for Masina, he had to rely on Bambara tonjon of doubtful loyalty. He soon had to tax and confiscate the wealth of his dominions to support the new ruling class, and to entrust power to provincial commanders who were often irresponsible. The smouldering resentment of the local subjects flamed into revolt, which led to repression and new confiscation and ultimately the exhaustion of the region 70.

Segu was the principal capital of the Umarian successor states. Where the centre of “paganism” had once flourished, the militant Islamic state now held forth. This led the Nigerian historian Oloruntimehin to entitle his treatment of the Umarian movement The Segu Tokolor Empire. At the same time it is hard to imagine a less successful economy, and a less imperial empire, than what Amadu ran out of his Niger palace. This gap between prestige and material basis is the fundamental contradiction of the Segovian state in the late nineteenth century.

Segu was the obvious choice for the Umarian headquarters. The Shaikh had designated it as the principal capital and placed Amadu there as his successor. Masina was not a candidate, since the wars which Umar and Bekkay unleashed continued for almost three decades. Karta was a more stable area, but it had been cast in a supportive role. Amadu, for his part, played up his role of successor in his dealings with North Africa, the Sahara, the savannah zone and the French 71. He added greatly to his prestige and the reputation of his city with his official proclamation as Commander of the Faithful in 1874 72. Even after he left the capital in the mid-1880s, Segu's symbolic identification with the whole Umarian enterprise remained.

In contrast to Karta, the Segovian section of the Umarian state failed to create an integrated economy. The reasons are not difficult to find. I have already stressed Umar's obsession with pressing his case against Masina. By taking away the vast majority of the talibe and sofas, including the wisest heads, he deprived Segu of force and leadership. The Masina wars took the lives of most of these men, diverted energies from production and trade, and interrupted the flow of caravans to the north-east. Amadu's inexperience and the bad counsel which he often received complicated the situation. Karta was often preoccupied with its own problems, or in revolt under a rival Tal, and consequently did not play the consistent supportive role which Umar had intended.

Table 7.3

Approximate Casualties and Prisoners in the Segovian Campaigns, 1859-66a

|

|

Date | Battle | Umarian toll | Opponent toll | ||||

| Statement on killed | Estimate or Figure | Statement on killed | Estimate or Figure | Statement on prisoners | Estimate or Figure | |||

| Conquest | 11/59 | Markoya | minimal | heavy | 500 | heavy | 500 | |

| 12/59-1/60 | Markoya counterattacks | some | 100 | very heavy | 1,000 | heavy | 500 | |

| 4/60 | Danfa | minimal | 2,500b | 2,500 | heavy | 500 | ||

| 5/60 | Ngano | minimal | 250 | 250 | heavy | 500 | ||

| 5-6/60 | Jawara expeditions | minimal | heavy | 500 | heavy | 500 | ||

| 8/60 | Jabal | some | 100 | very heavy | 1,000 | 600C | 600 | |

| 9/60 | Woitala | very heavy | 1,000 | very heavy | 3,000d | very heavy | 5,000 | |

| 2/61 | Tio | 500+ c | 750 | very heavy | 1,000 | heavy | 500 | |

| 4/61 | Koghe | heavy | 500 | very heavy | 1,000 | |||

| 4/61 | Pursuit operations | minimal | very heavy | 1,000 | heavy | 500 | ||

|

Sub-total:

|

2,450 | 10,750 | 9,100 | |||||

| Revolts and Repression | 3/63 | Segu plot | some | 100 | ||||

| 8-11/63 | Sinsani | heavy | 500 | some | 100 | heavy | 500 | |

| Bamabugu | 50 f | 50 | ||||||

| Wahina | some | 100 | ||||||

| Koghe | some | 100 | some | 100 | ||||

| Sukaro | some | 100 | ||||||

| Sama Marka | 150 | 150 | ||||||

| other | some | 100 | ||||||

| 11/63 | Kaba | some | 100 | |||||

| 11/63 | Segala | some | 100 | |||||

| Jonkoloni | some | 100 | ||||||

| 2/64 | Sinsani | 1,000+ | 1,000+ | some | 100 | |||

| 3/64 | Sinsani | some | 100 | |||||

| 4/64 | Fogni | heavy | 500 | very heavy | 1,000 | |||

| 7/64 | Tokoroba | heavy | 500 | some | 100 | |||

| Kuni | some | 100 | ||||||

| 8/64 | Faracco | some | 100 | some | 100 | |||

| 10/64 | Guni | some | 100 | some | 100 | |||

| 1/65 | Toghe (2 battles) | heavy | 500 | 2,500 | 2,500 | 3,500 | 3,500 | |

| 4/65 | Dina | some | 100 | heavy | 500 | |||

| 5/65 | Sinsani | very heavy | 1,000 | very heavy | 2,000 | |||

| 11/65 | Banankoro | some | 100 | some | 100 | heavy | 500 | |

| 3/66 | Maba | |||||||

| Falo | some | 100 | ||||||

|

Sub-total:

|

4,950 | 7,400 | 4,500 | |||||

|

Total:

|

7,400 | 18,150 | 13,600 | |||||

These factors helped the indigenous inhabitants of the Middle Niger to sustain rebellions throughout much of the late nineteenth century. These struggles never toppled the Futanke regime, but they did drain away its energy and sharply reduce its territorial extent. They resemble the pattern of revolt in Karta in 1855-6, and they began soon after the initial conquest. One form of rebellion came from the deposed dynasty 73. Kege Mari, the man who had plotted to eliminate his brother in 1858, used his legitimacy as the last surviving son of the great Monzon to mobilize soldiers of the old regime, including some who had submitted initially to the jihaad. He established a base south-east of the Bani River, launched his first offensive in 1863, and harassed the Futanke over the next decade. Three of his nephews successively picked up the resistance mantle in the 1870s and 1880s. The Jarra came much closer to embodying a popular reaction than the Massassi, and they found a secure base for revolt very close to the Umarian capital itself.

Another form of protest came from the Marka entrepreneurs who could not accept the terms of incorporation of the Futanke state. They had sworn allegiance in 1860 in hopes of playing their accustomed role within the regional economy. When they discovered that Amadu and his lieutenants would tax them heavily, confiscate goods arbitrarily, and accord them little autonomy, they revolted. The most conspicuous case of abuse and revolt was Sinsani, which took up arms in 1863 and maintained its independence until the French conquest in 1890. The struggle ended the town's prosperity and impoverished the whole desert-side of the Middle Niger economy 74. Nyamina did not revolt. It tolerated a Futanke garrison and became the gate of entry for caravans, soldiers and weapons from the west. But its most enterprising merchants left, its population shrank, and the town survived in a kind of sullen acquiescence 75. Some Marka relocated in Banamba, a centre north-west of the river and oriented towards the desert-side economy, and Baraweli, which faced the south and carried on some of the old functions of Nyamina. But these centres prospered more in spite of than because of the Futanke regime 76.

The revolts of the Jarra and the Marka and the attempt to suppress them took as heavy a toll of life in the Middle Niger as the initial wars of conquest. The figures in Table 3 do not include the casualties after 1866 nor the consequences of the jihaad for agriculture, livestock, and the stability of village life. These consequences do not match the devastation of Masina in the late nineteenth century, but they were extremely serious for the inhabitants of the region.

Another problem came from areas that had enjoyed considerable autonomy under the Jarra and never fully submitted to the jihaad. They were located on the left bank of the Niger, from the level of Bamako right up to the level of Sinsani. They played a particularly damaging role for a regime that relied on the west-east corridor for men and materiel. Once the caravans had passed through the secure reach of Nioro, they entered hazardous eastern Karta and the veritable chaos of the left bank. By the 1870s Amadu had established a cavalry escort for travellers between Tuba and Nyamina. Some of these travellers brought in the small arms which the regime purchased each year from Medine and Bakel 77.

With very few exceptions, such as the period of his maximum influence between 1874 and 1879, Amadu Sheku was not able to put down revolts or maintain security beyond the immediate heartland between the Niger and Bani Rivers. He could not restore the highly integrated economy, with its complementary specializations and zones, which the Jarra and Marka had managed in the early nineteenth century. He was equally unsuccessful in building a new system around the west-east corridor 78. He had only about 4,000 Senegambian talibe during Mage's visit in the 1860s. Some of them were posted out to garrisons in the heartland, along with the more numerous sofas. Some were located as far away as Tajana in the south, where they guarded the southern trade routes, or Murgula in the desolate Mandinka corridor. The morale was better for the talibe who stayed in the capital, but they in turn resented their lack of access to the palace. Many of them, in fact, wanted to go back to Nioro and Senegambia. To prevent this Amadu gave very specific instructions to his Somono boatmen and Nyamina garrison to block any desertions to the west 79. None of this was good publicity for new recruits and, coupled with the insecurity of the left bank, meant that very few people were added to the talibe contingent after the 1 860s. Amadu succeeded only in the 1870s, when he personally brought in a substantial number of Senegambian and Kartan followers, including sofas and tuburus as well as talibe 80.

The inner circle of the palace was dominated by members of the “Dingiray” group in the 1860s. They included the Nigerians, disciples from Fuuta Jalonke and the early days, and some griots who had attached themselves to the Tal family 81. Some members of this entourage could speak with Amadu in Hausa, which became a language of confidentiality at the palace. Added to this group were a few sofas, tuburus, and Moorish merchants from Tishit. Some of the talibe from Toro and the village clusters of Hayre and Halaybe had good access. In their case it was the ties of kinship and common origin which prevailed. The group that was most conspicuously left out consisted of the talibe from the central and eastern provinces of Fuuta Toro. In the 1870s and 1880s, the influence of the group from Toro, Hayre, and Halaybe took precedence over the Dingiray contingent. This was partly a question of age and of Amadu's ability to draw some new recruits from the Tal homeland. It may also have been a consequence of the revolt of Habib and Moktar, who drew their initial followings from the south and may have alienated this constituency from the ruler 82.

The Futanke regime of the Middle Niger consisted of a small garrison state, manned by talibe, sofas, and tuburus and sustained to a substantial degree by infusions of weapons from the west. The talibe learned Bambara and neglected Fulfulde. By their small numbers and arrogant demeanour they had little positive impact on the indigenous population. They used Islam as an additional basis of privilege. The local inhabitants, for their part, clung all the more strongly to their traditional practices and viewed Islam as the religion of the invaders. Soleillet's description of Bambara attitudes in 1879 is broadly representative of the evidence from late nineteenth century Segu:

“They [the Bambara] will not receive the marabouts [clerics], refuse to construct mosques in their villages, do not pray, do not observe the Ramadan, let their pubic hair grow, and wear mustaches. 83”

It is ironic that in the area which was most closely identified with the mission of Umar so little islamization was accomplished.

Notes

1. The Medine and Bakel information is contained primarily in ANS 13G 167 and 177 and in 15G 108. The quality of material in dossier 177 for June through Aug. 1860 is often good because based on information provided by Tambo, an Umarian who had arrived recently from the Beledugu theatre.

2. For the Middle Niger political economy, see Jean Bazin, “War and servitude in Segou”, Economy and Society 3.2 (1976); Charles Monteil, Les Bambara de Kaarta et Segou, 1924; Richard Roberts, “The Maraka and the economy of the Middle Niger Valley, 1790-1908” (Ph.D. thesis, University of Toronto, 1978), and “Long-distance trade and production: Sinsani in the 19th century”, JAH 1980.

3. For Senegambia, see the Report of the African Institution 16 (1822), pp. 330-2, and ANS 13G 164 and 15G 63; for Sierra Leone, see the Report of the African Institution 18 (1824), pp. 199-200, and Bruce Mouser, ed., Guinea Journals (1979), pp. 232-3, 244 (account of Staff Surgeon O'Beirne in Fuuta Jalonke); for Ivory and Gold Coast, see Hecquard, Voyage, pp. 4-10, 38 ff. and I. Wilks, Asante in the 19th Century (1975), pp. 56, 272, 312-14.

4. The rulers were Ngolo, the founder of the Jarra dynasty, his son Monzon and his grandson Da, and they reigned from c. 1750 to 1827. For the epic literature about these three figures, see L. Kesteloot and A. Traoré, Da Monzon de Ségou ( 1972), 4 vols, and S. Sauvageot, Contribution à l'histoire du royaume de Ségou (1965). A useful account appears in the 1868 edition of Mage (Voyage, pp. 397-405).

5. See the Roberts publications cited in note 2.

6. On the relationship with the Kunta clerics, see chapter 3, note 58.

7. The kings who ruled after Da Monzon (c. 1808-27) seldom figure prominently in Segovian oral tradition. On the excision of Masina from Bambara control, see chapter 2; on the removal of Tamba, see chapter 3.

8. On Jangunte see chapter 5, sections A and C.

9. This paragraph is based largely on the observations of Cerno Abdul himself, as reported in Mage (Voyage, pp. 143, 154-5). Some of Abdul's descendants could be found in the Middle Niger at the turn of the century (ANM 4E 92, Maki Beydi Aw, Bamako, 29 Aug. 1976). For an interesting view, based on a synthesis of Malian traditions, see Aliou Kone, “La prise de Ségou et la fin d'EI Hadj Umar”, NA 1978, pp. 61-5.

10. Robinson interview with Ba Cekoro Kulibali, Segu, 13 Aug. 1976. Similar accounts are found in Monteil, Bambara, and Tauxier, Bambara. The theme of the king's conversion is a Segovian tradition and does not emerge in the Umarian chronicles except for Mage's. Mage (Voyage, p. 155) has the king decapitated, but Segovian tradition suggests that the tonjon avoided spilling royal blood.

11. Monteil, Bambara, pp. 99-100, 130; Tauxier, Bambara, pp. 106-11. Koné (“Prise de Ségou”) maintains that Torokoro Mari converted at the time of Umar's initial passage through Segu in 1840.

12. I have dated the change in regime to 1858 on the basis of several factors: Mage's insistence, based on his first-hand information from Cerno Abdul, on a reign of 4 to 5 years for Torokoro Mari (see Voyage, 1868 edn., p. 403), and his timing for the events beginning with the Jangunte campaign in 1856 (Voyage, 1867 edition, pp. 154-5); the recurrent tradition whereby Ali lost Segu in the 3rd year of his reign, which argues for accession in 1858; and the archival record which indicates an upsurge of revolt in Karta in late 1858 (ANS 15G 108, entries for 7, 13, and 27 Oct. and 7 Nov. 1858). It is interesting to note the similarity of Torokoro Mari's deposition to that of Osei Kwame in late eighteenth century Asante (J. Dupuis, Journal of a Residence in Ashanti, 1824, p. 245; Wilks, Asante, pp. 252-4).

13. The rhetoric is most intense in Segu 3/Cam and Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali.

14. The indications of desertion are found in the letters of the commanders of Medine, Bakel and Matam for 1859-61 (ANS 13C 157, 167, 177 and 15G 108).

15. The two bronze howitzers had been captured at Njum in Ɓundu in 1858. The other pieces were probably two copper cannon (pierriers) used sparingly in Masina, and two iron mortars (espingoles) which Amadu tried to use in Segu to little effect. The mortars were probably taken at Manael in August 1855. See ANS 13G 177, piece 26 (letter of 26 June 1860), and Saint-Martin, “L'artillerie d'El Hadj Omar et d'Ahmadou”, BIFAN, B, 1965.

16. In addition to the sources in the previous note, see ANS 13G 177, letter of 23 July 1860; Mage, Voyage, p. 161.

17. For the negotiations, see chapter 6, section E.

18. The only detailed source on Alfa Uthman's campaign in 1857-9 is Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali. Information from a largely Mandinka perspective may be found in J. Galliéni, Voyage au Soudan français, 1879-81 (1885), pp. 578 - 90; A. Perignon, Haut-Senegal et Moyen Niger (1907), pp. 81 ff.; G. Tellier, Autour de Kita (1898), pp. 23 ff.; and in ANM 1D 32 (Bafoulabe) and ANS IG 41 (Galliéni, 1879-80), 50 (Vallière and Piétri, 1879-80), and ID 69 (Galliéni, 1879-80). Alfa Uthman conquered the areas of Betea, Farimbula, Gangaran, Banyakadugu and Gadugu, between the Bafing and the Bakhoy; Fuladugu, Kita and Birgo between the Bakhoy and the Baule; and Bure and Manding on the northern bank of the Tenkisso and the Niger. All of these areas were Mandinka except Fuladugu, where Fulfulde was spoken. Uthman meted out the harshest punishment to Farimbula, Gangaran, Manding and Fuladugu.

19. Robinson interview with Mamby Sidibé, Bamako, 5 Sept. 1976. For the nickname of “white hand”, see Perignon, Haut-Sénégal, p. 94. Mage (Voyage, pp. 50 ff.) thought that the population was simply exterminated in some areas.

20. See chapter 3, note 103.

21. For a sketch of Murgula, see Galliéni, 1879-81, p. 287.

22. For the chronology of the final victory at Bangassi, I have relied on Mage's statement ( Voyage, p. 162) that it virtually coincided with the victory at Markoya and can thus be dated to late November 1859. Bangassi is the only one of Alfa Uthman's conquests which has entered the other Umarian materials. The Dingiray chronicle mentions how difficult it was to capture (p. 313 of the Reichardt translation).

23. For Amadu and Makki, see chapter 3, section C, especially notes 40-1.

24. The message sent to Dingiray via Abdullay Hausa is found in BNP, MO, FA 5718, fo. 1. Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali states that the message was sent from Bagowoyni in Bakunu, not from Nioro.

25. According to Bambara tradition, powerful charms were placed in Markoya to prevent Umar's entry—to no effect obviously. Monteil, Bambara, pp. 341-2. During Umar's stay in the city he exchanged a number of slaves, probably captured in the area, for salt brought by a Tishit caravan. P. Marty, “Chroniques de Oualata et de Nema”, REI 1927, p. 367; M. H. Vincent, “Voyage d'exploration dans l'Adrar”, Tour du Monde, 1861.3, p. 58.

26. For Dingiray during the 1850s the material is very sparse and it is impossible to develop a coherent picture. See BNP, MO, FA 5559, fos. 164-5; 5595, fo. 128; 5714, fo 90; 5723, fos. 22-3. In the French archives, see ANS 13G 167, letter of 16 Dec. 1855, and 15G 108, letters of 22 Sept. and 14 Oct. 1857 and 4 Jan. 1858, together with the MSD of 4 Aug. 1857. See also Dingiray/Reichardt, p. 309 of the translation.

27. Dingiray/Reichardt, pp. 264-5 of the Fulfulde, pp. 312-13 of the translation. It is possible that Alfa Uthman had already created some resentment in the Umarian ranks in late 1858. During the revolt led by the Jawara with Segovian assistance, Uthman received a letter from Umar, or possibly Alfa Umar Baila, to join the defence of the eastern frontier at Jala. It is not clear whether Uthman responded to that call. Bandiagara/ Abdullay Ali, pp. 16 and 18 of the Brevié Arabic text, p. 11 of the Cissoko translation.

28. Mariatu, Makki's mother, died in 1847; he was subsequently raised by his mother's servant. De Loppinot, “Souvenirs”, p. 26. See chapter 1, note 40, and chapter 3, note 40. The descendants of Agibu have been responsible for maintaining a tradition whereby Makki was as old or older than Amadu and destined to rule. In fact Makki acknowledged Amadu as his elder. BNP, MO, FA 5457, fo. 1; 5716, fo. 32; 5737, fo. 59.

29. BNP, MO, FA 5723, fos. 22-3.

30. Mage, Voyage, p. 172. See also the comment contained in ANS IG 32, piece 23 (a May 1865 report from the Rio Nunez). 31. BNP, MO, FA 5683, fo. 151. The succession at Markoya is not mentioned in the Bandiagara source, which limits itself to saying that Amadu, Makki and Tijani, its patron, joined the main army at Markoya. More interesting is the absence of reference in Mage and in the words communicated by the Soninke talibe Tambo to the commander of Bakel in June 1860 (ANS 13G 177, letter of 26 June 1860). Tambo may have left Markoya before the late February ceremony.

32. BNP MO, FA 5683, fo. 151.

33. Mage, Voyage, p. 163. See Cissoko, “Guerre sainte”, pp. 718-20. None of the internal narratives mentions the return of the dependants; Segu 3/Cam (p. 134) only cites the talibe' escort. See chapter 6, section E.

34. There were several minor battles at Markoya, against forces from Beledugu and Segu proper.

35. Segu 3/Cam, pp. 136 and 141.

36. The first encounter came at Damfa, the second at Ngano. Ngano is particularly remembered in Bambara traditions since it involved the Segovian army. See Ta'rikh Bamako; Kulibali interview cited in note 10; Lanrezac, “Au Soudan: la légende historique”, RI (1907), p. 420.

37. Here I have drawn principally on a series of interviews with Marka elders and others conducted by Richard Roberts in July and August 1981, in Banamba, Touba, Sinzena, and Nyamina. In Nyamina the dominant Sakho lineage emigrated in massive proportions with the approach of Umar, but the other lineages accepted Futanke overrule with few qualms, at least in the initial stages.

38. This strategy emerges from a close scrutiny of the timing of events.

39. For the Jawara episodes, see Blanc, “Jawara”, p. 97.

40. Dingiray/Reichardt, p. 267.

41. For the Bambara traditions, see the interview with Kulibali cited in note 10 and the Robinson interview with Almamy Jawara, Segu, 14 Aug. 1976. The Woitala events are sufficiently important to emerge briefly in the Dingiray and Nioro chronicles, but the main sources are Segu l/Mage, Segu 3/Cam and Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali. Another detailed version appears in Capt. Bellat, “Renseignements historiques sur le Sansanding et le Masina”, 1893, ANS IG 184.

42. Mage, Voyage, p. 165.

43. On the toll of Woitala, see table 3, note d. It is likely that Tata ran out of ammunition.

44. On the impressions made, see Segu 3/Cam, pp. 152-3; Roberts, “Maraka”, pp. 74-6. A full account is found in the Bellat monograph cited in note 41. Umar also sent a mission to Morocco from Sinsani; it is described in note 68.

45. BNP, MO, FA 5605 (Umar's Bayan), fos. 4 ff. and esp. fo. 27; Bellat, “Renseignements”, pp. 122-3; Capt. Underberg, “Notes sur l'histoire du Macina”, in ANS IG 122; Samb, “Omar par Kamara”, p. 113. Bellat and Underberg suggest that Ali may have submitted in 1859 or early 1860. However, the confidence of the Bamana leadership and the absence of Masina troops at Woitala suggest that no agreement was concluded and no allegiance sworn before the Woitala defeat.

46. In addition to Bellat and Underberg, see Delafosse, Haut-Senegal-Niger, vol. 2, p. 295, and the Masinanke document Maa Jaara (see chapter 1, note 40.

47. This quotation comes from a polemical document written by Yirkoy Talfi in 1862 and entitled Tabakkiyyat al-Bekkay (BNP, MO FA 5697, fo. 40v; CEDRAB 240, fo. 31). The same passage is translated in Willis, “Doctrinal basis”, pp. 308-9, and Samb, “Omar par Kamara”, p. 371. For Umar al-Awsi's accusations against al-Bekkay, see 5606, fos. 182-4; for al-Bekkay's defence, see 5259, fos. 68-70.

48. Maa Jaara. The same statement can be found in Umar's Bayan (BNP MO, FA 5605).

49. For the rich documentation on the Masina-Futanke controversy, see chapter I, section D, and chapter 8.

50. Curtin interview with Saki N'Diaye, Dakar, 6 Apr. 1966. The scholar who read Umar's letter was Alfa Haimut Ba.

51. BNP, MO, FA 5684, fos. 138-42.

52. The ultimatum appears in BNP, MO, FA 5605, fo. 4; Maa Jaara; Mage, Voyage, p. 167; Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali.

53. Umar gave quite specific instructions to his men not to attack. Bellat, “Renseignements”, p. 129.

54.Tio is also spelled Tyo and Tayo. The main sources here are those cited in note 41. Internal sources claim that Umar tried to concentrate the attack on the Bambara army. Dates for the 1861 campaigns are found in BNP, MO, FA 5740, fo. 148.

55. Segu 3/Cam, p. 161.

56. Dingiray/Reichardt, p. 269.

57. Tour du Monde, 1861, p. 26. This information probably came through Medine or Bakel sources.

58. This leader came to Segu a few years after 1861, and wrote this statement in a letter dated March 1866. Salenc, “La vie”, p. 413. The same material is found in the original Arabic in BNP, MO, FA 5484, fo. 115.

59. For Koghe and the pursuit operations, see the sources cited in note 41.

60. The Somono of Sinsani had submitted at the same time as the Marka of their city and transported the Umarians across the river to do battle at Tio. Marka sources (Roberts, “Maraka”, pp. 71-90) usually suggest that the Somono of Segu and Nyamina remained loyal to Ali until March of 1861.

61. The capital was Segu Sikoro, as distinguished from Segu Bugu, Segu Kura and Segu Kora, all located along the river to the west. The population estimates are adapted from Mage, Voyage, p. 198. The Umarian army numbered about 25,000.

62. Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali, p. 135 of Cissoko translation; Mage, Voyage, p. 210n. Umar's reputation for generosity would later be contrasted with Amadu's parsimony. Mage, Voyage, pp. 205-6.

63. Umar also prohibited the consumption of the meat of dogs, horses, or sick animals. Segu l/Mage, p. 169; Segu 3/Cam, pp. 168-71.

64. On the objects see Kesteloot, Da Monzon, vol. 1, pp. 60-1; Monteil, Bambara, pp. 253-7, 182; Segu 3/Cam, p. 184. The destruction of “idols” is a more important theme in West African traditions than the internal narratives might imply. Sunjata destroyed the Sosso objects, according to the accounts of griots (Niane, Epic, pp. 41, 69, 76, 82) and Samori's generals crushed “idols” in the 1880s (Person, Samori, vol. 2, p. 813).

65. Mage, Voyage, pp. 127 ff., 276-7.

66. The only source on the trip from Dingiray under the escort of Umar al-Awsi is Bandiagara/Abdullay Ali. On the installation, see Segu l/Mage, pp. 171 -2; Segu 3/Cam, p. 175.

67. ANS IG 32, piece 35, pp. 9 and 28 ff. The Segovian reign may well have depleted Bure of its wealth, for Winwood Reade found it poor in 1870. See his letter in BSGP 1870, pp. 235-8.

68. For the Markoya trade with Tishit, see note 25. For the contacts with the Sultan of Morocco, who sought but probably did not receive Umar's help against the Spanish in Tetuan, see Bou-El-Moghdad Seck, “Voyage par terre entre le Sénégal et le Maroc”, RMC 1861. Seck saw the group in February 1861 heading for the Middle Niger. Umar also corresponded with al-Kansusi of Marrakesh right after Woitala. BNP, MO, FA 5573, fos. 62-3.

69. ANM 1D51.1; 1E71 for 1891.

70. The principal source for Amadu's predicaments is Mage.

71. Systematic research into Amadu's correspondence in the Segovian materials in Paris will show just how extensive this role was. An inventory in French and Arabic of these Segu archives, or the Fonds Archinard as it is usually called, will be published under the auspices of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique of Paris. The inventory was prepared under the auspices of a 1978 grant of the National Endowment for the Humanities to Yale University.

72. See chapter 5, note 41.

73. See Mage, Voyage, pp. 197 ff; Tauxier, Bambara, pp. 164 ff. Another rich and rarely exploited source on the revolts is Nioro 2/Adam, and some of the same material is found in Nioro 3/Delafosse.

74. On Sinsani in the late nineteenth century, see Roberts, “Maraka”, pp. 71-90.

75. Mage Voyage, pp. 106-21, 369 ff.; and the Nyamina interviews of Roberts cited in note 37.

76. Roberts, “Maraka”, pp. 99 ff.

77. Saint. Martin estimates 1.500 to 1.800 small arms per year (Empire, p. 61 ) based on his work in the Medine and Bakel archives. For the escort service, see E. Ann McDougall, “The Ijil salt industry: its role in the precolonial economy of the Western Sudan”, (Ph.D. thesis, Centre of West African Studies, University of Birmingham, 1980), pp. 247-8; Soleillet, Voyage, pp. 272-3.

78. Emile Baillaud (Sur les routes du Soudan, 1902, pp. 61 ff.) declares that the jihaad ruined Bamako, Nyamina, Segu, and Sinsani by trying to impose an east-west orientation on an economy that ran in a north-south direction. I agree with the effect of ruin and decline. I would argue that Umar and to some extent Amadu did recognize the orientation of the economy, but that the structure of the jihaad and the pattern of revolt prevented them from restoring that orientation. Amadu's Segu could survive, after 1863, only as the eastern edge of the Umarian movement.

79. Mage, Voyage, pp. 448-9.

80. ANM IE 71, 1891; Nioro 2/Adam, pp. 178 f.; Nioro 3/Delafosse, p. 365, Soleillet, Voyage, pp. 377 ff.

81. For Amadu's entourage, see Mage, Voyage, pp. 136-8, 207-8, 423-7, 441-5. The griots included members of the old Tamba court. See chapter 3, note 106.

82. The Ture brothers from Hayre, Seydu Jeliya, Mustapha Jeliya, and Abdullay Jeliya, were the most prominent members of the inner circle in the later period. They were kinsmen of the Sakho and Tal and married several of the Tal women. See Soleillet's impressions of them in ANS IG 46, piece 2; chapter 9, table 3.

83. ANS IG 46, piece 8, p. 20. See also the Roberts interview with Ismaila Fane at Tesserela, 30 July 1981; ANM ID 55, piece 3 (1907 statement); E. Caron, De Saint Louis 2 Tombouctou ( 1891), p. 338; Marty, Soudan, IV, pp. 63 ff., 176 ff.