Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1985. 420 pages

From the perspective of many West African clerics, the first great age of Islam in the savannah came with the Songhay Empire of the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. It was then that Askiya Muhammad made his pilgrimage and waged his jihaad against the Mossi. It was then that the itinerant preacher al-Maghili gave his advice to the Askiya and other sultans about how a Muslim should rule. Several generations of scholars made Timbuktu an important intellectual centre. Some of them provided the indispensable chronicles of savannah dynasties. Ahmad Baba provided a widely used distinction between the areas constituting the Daar al-Islam and those making up the domain of ‘paganism’ 1.

According to this internal perspective, the fortunes of Islam declined after the Moroccan invasion of 1591 and rose again only in the eighteenth century 2. The dominant factor in the resurgence was the emergence of the Fulɓe jihaads, especially the highly intentional ones in Hausaland and Maasina. There the new philosopher kings saw themselves in a direct line of intellectual descent from Askiya Muhammad, al-Maghili and Ahmad Baba. By following the classical Muhammadan formula they had recreated the Dar al-lslam in West Africa. They applied the criteria of al-Maghili to the practices of courts and societies. They transformed the religious geography of Ahmad Baba by extending the Daar al-Islam to new areas 3. This perspective of progressive islamization and state formation, articulated by indigenous Muslim scholars and reinforced by Western Islamicists, has dominated the interpretation of the jihads, including the one led by Umar Tal. This chapter examines the suitability of that perspective and of alternative frameworks for understanding the Umarian movement.

All four Fulɓe-dominated states played a significant role in extending the reach of Islam in the savannah. All to varying degrees laid the basis for the Umarian movement. Their ruling classes created new institutions of government and education. They perceived themselves as a chosen people who spoke a language superior to all but Arabic. They had an aptitude for scholarship, politics, and war. If they could ensure a continuing flow of slaves to support the material needs of the society, they could provide security, instruction, and prosperity for their citizens.

When these systems of Islamic government did not fulfil the expectations of future generations, many Fulɓe were susceptible to recruitment in new ventures. Umar Tal took centre stage when disenchantment was high, and he built his movement upon the educated but dissatisfied men of the Fulɓe societies. He grew up in a Fuuta-Toro obsessed with its failure to create a strong and equitable Islamic society. He stayed on two occasions in a Fuuta-Jalon riven by civil war. He visited Hausaland at the end of its golden age. He learned from the works and example of the founders, but he also witnessed the entrenchment of the ruling class and drew some of the dissatisfied to his own side. He saw Maasina in a roughly comparable period and attracted a similar, highly articulate coterie of followers.

Umar brought important credentials and talents to his interaction with these Fulɓe societies. While he made little impression on his journey out to the Holy Lands, his return as pilgrim and Tijaniyya leader aroused admiration and animosity. His new titles made people pay attention to his eloquence, his mastery of Islamic law and theology, and his confidence in his proximity to Ahmad al-Tijani. Indeed, Umar escalated the criteria for Islamic distinction in the nineteenth century. He became a counsellor, teacher, interpreter, problem-solver, and miracle-worker. By dint of the campaigns in jihaad he became an effective military strategist. He acquired all of the qualities requisite for leadership in mid-nineteenth-century West Africa save one: experience in administration. The positive responses which he received from many Fulɓe, and the lukewarm and sometimes hostile reactions which came from many non-Fulɓe, gradually fed the Shaikh's sense of ethnic consciousness. In the context of the jihaad, ethnic solidarity would become more important than Tijaniyya affiliation.

It is this juxtaposition of Islamic and Fulɓe institutions, substantial disenchantment, and the striking professional and personal qualities of Umar which created the opportunity for holy war. The institutions and the disenchantment are played down in the internal chronicles, but only they can explain the strong Fuutanke affirmation of the jihaad and those instances where the followers forced the leader's hand. Ultimately the movement showed a remarkable coincidence of interest between leader and follower and a momentum that increasingly swept both along.

It is none the less appropriate to speak of an ‘Umarian’ jihaad. The movement often ground to a halt when the Shaikh was away; campaigns were often not worth recording if he was absent. It was Umar who initiated most of the significant action. He might withdraw into meditation, consult with his closest disciples, or install Amadu as administrator of the state, but he was the one who defined issues and made the ultimate decisions. His military tactics were shrewd and sometimes brilliant. His intuition for an opponent's weakness was uncanny. His sense for the symbolic act was acute. His reserves of energy seemed inexhaustible. The most striking illustration of these qualities came during the period from 1857 to 1859, when Umar rebuilt morale, articulated a new strategy of recruitment, dared to challenge French and Fuutanke at Hoore-Fonde, and then led and bullied his thousands back to Nioro. The Shaikh was a genius in a propitious time. He was a man whose head, shoulders, and chest, in the words of the griot, were uncommonly wide 4.

At the same time he was a person of some years who was determined to make his mark quickly. He did not like to share responsibility. He had little penchant for explanation or training, not even for his own sons. He could be vain about his reputation and let others take the blame for the loss at Medine or the assassination of Amadu mo Amadu. He could be so preoccupied about his own purity, about ‘not frequenting the courts of sultans’, that he neglected the administration of his own dominions. He could show excessive cruelty, as in the execution of the Jawara. These characteristics were the corollary of his strengths. The genius spawned a movement which grew dependent upon him and lost much of its drive when he died.

Umar did not fashion the structure of the jihaad abruptly or alone. He reflected deeply about the Dar al-lslam and state formation in his years at Sokoto. It was there that he started his own family and attracted his first circle of followers. In Jegunko he moulded family and following into a loyal band ready to support his career. The completion of his major treatise marked a certain fulfilment in the role of scholar and freed him for the exploration of new horizons. He achieved some satisfaction from intervening in the Alfaya-Soriya quarrels in Fuuta-Jalon. In the process he realized that he could not accede to power in the old Fulɓe structures without producing intense conflict. The effects of the later struggle in Maasina confirm, in retrospect, the wisdom of this judgement. The testing journey established the link between Tijaniyya affiliation and jihaad. It confirmed Umar in his reliance on a Fulɓe constituency and demonstrated that he could attract a following from his homeland committed to holy war. This new constituency then encouraged him to take the next step, the move to Dingiray and a more appropriate political arena. There leader and follower together forced the confrontation with ‘pagan’ power and created the initial momentum of jihaad. That Umar shifted his vocation from teacher in Jegunko to warrior in Dingiray there can be no doubt 5. But his multifarious talents and strong ambition were in evidence from the time of the pilgrimage, and he moved along the road to jihaad by a series of logical tests.

The move to Dingiray foreshadowed the structure of the entire jihaad. The men and matériel would come from the ‘west’, defined as Guinea and Senegambia. Most of the men would be Fulɓe Muslims who were products of the pedagogical systems and representative of the widespread dissatisfaction in Fuuta-Jalon, Bundu, and Fuuta-Toro. These Fuutanke were not always in the numerical majority in the movement, but they were absolutely critical to the prosecution of the war. They shared Umar's background, they made his cause their own, they left their name—Fuuta, Fuutanke— in the traditions of the people they invaded. The supplies consisted of the guns, powder, and bullets sold by the British in Freetown and the Gambia and by the French along the Senegal, and then transmitted by middlemen who were active or latent partisans of the cause. Yimba symbolized the societies of the ‘east’, largely Mandinka and Bambara and non-Muslim. The principal targets were the ‘notorious pagans’, the courts which had developed a national identity around a collection of priests, age-grades, ceremonies, and cult objects. The ‘jihaad against paganism’ was an imperial war, an extension of the Fulɓe Dar al-lslam into new areas. It was a crusade, not to liberate a Jerusalem or protect persecuted minorities, but to destroy the offensive temples of ‘infidelity’. It was an outlet for frustration at societies that could not fulfil the spiritual and material goals of their founders and an opportunity for the truly faithful to start afresh, with a new community, land, slaves, and position. In its fervour, confidence, and ambition to surmount daunting odds of distance and supply, the Umarian jihaad bears a striking resemblance to the First Crusade of the ‘Franks’ in 1095-9 6.

At the beginning the Shaikh used some camouflage. First, he pretended to be a simple cleric and paid tribute to the king of Tamba. This mask was dropped in 1852 and all but buried in the embarrassed chronicles. Second, he mingled his goals with those of a reluctant Almamy, who sought to extend Timbo's reach to the east. This convergence helped bring in the recruits necessary to defeat Tamba and gain direct access to the gold of Bure. With the march north in 1854, Umar showed that his goals went far beyond the traditional objectives of Fuuta-Jalon. His territory might belong to the growing Dar al-lslam, but he would direct its fortunes.

The move to the north marked the first shift within the west-east structure. It was primarily an escalation in the scale and direction of recruitment. While an army of 2,500 might suffice against Tamba, 10,000 to 15,000 would be required against the Bambara. The cost of such an expansion was the loss of the intimacy and flexibility which the Umarian community had enjoyed in an earlier day. With his characteristic sense of timing, the Shaikh turned to the eastern Senegambian societies who shared a grievance against Kartan hegemony and acute dissatisfaction with their own regimes. He chose his envoys carefully for their ability to link local issues to the overriding importance of the jihaad. Nowhere were the grievances and responses greater than in Bundu, exhausted by civil war, and Fuuta-Toro, fragmented by divisions and perplexed in the face of French aggression. Fuuta was able, on this and subsequent occasions, to supply the level of manpower required. It dominated the talibé ranks in numbers if not always in influence, from this time forward. Umar was now in firm control of eastern Senegambia. He could implement a boycott on trade to counter the arms embargo, confiscate weapons from commercial factories, and install a series of relay stations. These posts were not unlike the ribaats created by Muhammad Bello, but they served not so much the purposes of defence as the requirements of recruitment 7.

The arms embargo and Podor fort turned into a pattern of expansion under Faidherbe, which brought on the confrontations of 1857-9 and a fundamental revision of the structure of the jihaad. The Shaikh, obliged to replenish his forces and arms after the Kartan revolts, encountered a system of forts, gunboats, and chiefs that far exceeded the modified dhimmi conventions of Senegambia. After the devastating clash at Medine, Umar and his antagonist found ways to avoid new battles, and each achieved his main goal: massive recruitment, on the one hand, and the installation of gold-mining operations on the other. Both moved quickly to the arrangement of 1860, which had the effect of sharpening the geographic division of the jihaad. Umar could still trade, mobilize, and arbitrate, but he could no longer reign in the ‘west’. The more organic bonds which he might have forged between recruiting area and settlement area, between European manufactures and Kartan livestock, between older Islamic cultures and new institutions of islamization—these possibilities were now sharply diminished. In addition, the growing French presence forced Umar to speed up his mobilization, to extract the last ounce of men and matériel. That massive mobilization in turn tipped the ecological and productive balance of the upper valley.

Within the logic of the imperial jihaad, the changed situation in Senegambia made a new centre on the Middle Niger all the more urgent. Umar had intended to attack Segu for some time. In 1856 he installed a large garrison at the Segovian frontier. In 1857 he dispatched Alfa Uthman to develop a salient in the Mandinka corridor. In 1859 he and his followers, with their vast territorial commitments and swollen ranks, simply had to move quickly to an area of agricultural abundance. They had little capacity to organize the production of a food surplus in Karta and they could extract no more from the teetering economy of the ‘west’.

The imperial jihaad did achieve a momentum which went beyond French expansion, Senegambian exhaustion and the desperate need for new granaries and livestock. From the beginning the jihaadists had expected quick rewards, ranging from material booty to new community. Success in creating rewards generated new recruitment. The slaves captured in one campaign induced new mobilization. But the spiral could run down as well as up: lose the battle of Medine and watch the desertion grow. Umar's problem between 1857 and 1860 was that he had no rewards for the new masses for whom he had evoked such a glorious future. He had not mobilized these people to raise millet and cattle in Karta, and they did not yet have the slaves to do the work for them. By precedent, and by his and their disposition, Umar could not delay their gratification in a strange land. It was Segu, with its grain and gold and labour force, which beckoned, and it mattered little whether Torokoro Mari or Bina Ali was in power. In that respect the defeat at Medine required the victory at Woitala, which in turn saved the jihaad not only from the Bambara but also from self-destruction.

The late 1850s consequently mark a watershed in the history of the Umarian movement. The west-east structure was maintained, but it was extended to new lengths on the Middle Niger and to new depths in its impact on Senegambian and Malian societies. The campaigns against Tamba and Karta were built upon old frustrations and desires for liberation. Enlistment was often spontaneous and temporary. By contrast, the momentum which developed after Medine was driven, intense, and permanent. The community forged in the convalescence of Kunjan had to recruit massively and coercively in Senegambia, had to march into the Middle Niger in the ‘hungry season’, had to slough off its women and children at Markoya. They must die or conquer, as Umar pungently commented at Woitala. They had covenanted together, in the words of Makki and Tijani at Cayawal, they had become a new breed, a new ethnic group. The intensity was reflected in a new ideological tone: anyone who was not for the crusade was against it, anyone could become ‘pagan’ by opposition to the jihaad and association with its enemies. Segu was the pinnacle of achievement for the jihaad.

The notorious capital of ‘paganism’ was now the capital of the Daar al-Islam of the Western Sudan, celebrated by Muslims in West and North Africa. It is from this time that the titles ‘Commander of the Faithful’ and khaliifa are more frequently applied to Umar, who in turn made a consistent effort to transfer them to Amadu Sheku 8. Amadu governed, or attempted to govern from Segu for two more decades. The west-east structure was now stretched over a vast distance, and it fell to Karta to sustain the flow of men and matériel from the ‘west’. But Umarian Karta, in the absence of its charismatic leader and amid its own preoccupations, was not able to fulfil the task. The result was that the momentum waned and the empire began to shrink down to garrison islands in a generally hostile sea.

It is correct to view the Maasina campaign of 1862 as an extension of the momentum of the imperial jihaad. The jihaadists viewed it in that fashion. The victory at Cayawal paved the way to immediate rewards and delayed the time of reckoning a bit longer. But Umar, who was still making the decisions despite his age and the installation of Amadu, had also to consider the expedition from another angle. As the leading interpreter of Islam in his generation, as one who had publicized his achievements to the wider Muslim community and called for reconciliation between Bornu and Sokoto or Alfaya and Soriya, he could not countenance an attack upon another Islamic state. Hamdullahi had harassed his Tijaniyya followers, disputed the jihaad in eastern Karta, and presumably let the quality of its own Islamic society decline. It had negotiated with the ‘pagan’ king of Segu through most of 1860. But Umar was not committed to confrontation with Maasina at that time. Until he received the letter with Hamdullahi's inflated claims and the ultimatum marking the failure of his delegation, the Shaikh expected Maasina to acquiesce in and cohabit with a Fuutanke Segu.

Once those direct challenges were issued, once Amadu III suggested that the transfer from ‘infidel’ to Muslim could be so mechanistically achieved by an inconsistent Maasina state, Umar shifted from a defensive to an offensive posture. Amadu III must repudiate his actions or fight. The momentum of the jihaad had engaged the pride of Hamdullahi. As a consequence, the campaign against Amadu III became a question of time and timing. But it did require a very specific justification, written not after the fact as in the case of Sokoto and Bornu, but before the expedition. That justification assimilated Amadu III to the status of ‘pagan’ and made the campaign and extension of the ‘jihaad against paganism’.

The argument was eloquent but it did not penetrate much beyond the Umarian circle. The attack of Muslim against Muslim, together with the physical over-extension of the jihaad, eventually undermined the movement. Even scholars who were seduced by the logic of the Bayaan shrank from the combat of Cayawal. Others waited to see what kind of administration would be established. When it became obvious that the jihaadists would not restore the Bari lineage and leave, they intervened. Ahmad al-Bekkay, wary of the Tijaniyya threat for decades but constrained by conventions of appropriate action, now buried convention and unleashed the coalition that buried the jihaad. It was ultimately the relentless coordination of Bekkay which distinguished the Maasina revolt from its analogues in Karta and Segu.

Between Cayawal and the revolt Umar gave indications of his vision of the jihaad. He was still resistant to consolidating control and building sound institutions. In so far as administration was concerned, Amadu and the second generation of Tal could handle the task. Meanwhile the leader would direct a kind of jihaadic militia to ensure the allegiance and police the practice of the Western Sudan. If the ‘pagan’ temples and priestly hierarchies could just be destroyed, Islam would grow up in their place. The new domain stopped roughly where the Caliphate of Sokoto and Gwandu began, and it covered a comparable area. The Umarian jihaad had done its part in extending the Dar al-lslam in West Africa, or at least in destroying what stood in its way.

The insurrection put a resounding end to such plans and destroyed the best leaders and most committed followers of the movement. It accelerated the shrinkage of the empire down to its fortress islands. It is ironic that Tijani, left with by far the smallest number of talibe, was the only successor of Umar to recreate some of the momentum of the original jihaad. More fundamentally, the long and triangular struggle between Fuutanke, Masinanke Fulɓe, and Kunta trivialized the religious and ethnic basis of the Umarian enterprise. Muslim Fulɓe were fighting each other and destroying their leadership in the expansion of the Dar al-Islam. The jihaad was now any campaign for any advantage over any foe. The conventions articulated by Umar in his Bayaan, and more pompously by Bekkay over a whole lifetime, were forgotten.

The west-east structure lasted through the twelve years of fighting. It worked effectively for Tamba and Karta, stretched to encompass Segu, and burst at the seams in Maasina. Each of the main targets forms a convenient period and division of the jihaad: the smaller scale of operations around Tamba (Chapter 3), the more massive mobilization against Karta (Chapters 4 and 5), the equally massive and logistically dangerous campaigns against Segu (Chapter 7), and the triumph and disaster in Maasina (Chapter 8). The first two periods fall during the first phase, when Senegambia and Guinea were contiguous with the arena of combat. The last two form the second phase, when supply lines were strained and the centre of gravity lay on the Niger. In between the two phases intruded French expansion and the confrontations of the late 1850s (Chapter 6) 9.

The Maasina blockade marked the first reversal in the decisive advantage in weapons which the jihaad had always enjoyed. Until that time the Umarians had fought with the coast and sources of European arms at their backs. Through Freetown, the Gambia and the Senegal Rivers, and somewhat later via the ports of the Nunez and Pongo, they dominated access to these instruments of war 10. The positioning was a conscious choice, and it reinforced the emphasis on Fuutanke recruitment and the west-east structure of the jihaad.

The movement was predicated initially on a relationship with Europeans that approximated the Islamic concept of dhimmi, ‘protected enclave’, and to local metaphors like ‘master of the water’. Europeans occupied strategic points along the coast and rivers. They were concerned with imports and exports. They coordinated their structures with the trade diasporas of the interior. They did import most of the firearms, and they could mount their cannon on boats to destroy a village. But they had no cavalry for pursuit, no quinine to stop malaria, and little inclination to become ‘masters of the land’ 11. The French did not contravene these assumptions much more than the British—until 1854.

Louis Faidherbe bristled at the idea of dhimmi status and paying tribute to indigenous authorities 12. Under his leadership the French developed a serious military capability. They operated throughout the year from a chain of riverine forts linked by steamboats. They maintained cavalry and infantry, many of them black, to punish their enemies. They could inflect the flow of weapons towards friends and away from foes, ‘liberate’ some slaves, and return, indeed sell, others. They could establish protectorates, name chiefs and subsidize their rule. By the end of 1857 the French were masters of the crucial arteries of recruitment and trade in the Senegal valley.

In the face of this Umar had to modify his initial assumptions about controlling Senegambia and obtaining weapons. He had always diversified his sources of firearms. He could surmount the arms embargo in part by persuading and pressuring traitants or by raiding factories, especially in the low water season when he still had an edge over his adversaries. But these were inferior solutions, especially for the second phase of the jihaad, and the Shaikh moved with dispatch to establish the 1860 arrangement that permitted a steady flow of weapons to the ‘east’.

The Umarian state after 1860 fits some of the definitions of ‘secondary empire’. Philip Curtin uses the term to designate an African state which uses European military technology to its own advantage, but which often collapses by its failure to maintain the arms monopoly. The Turko-Egyptian regime of the Sudan is often put forward as an example 13. The definition applies to the regime of Amadu Sheku at several points. Segu depended on European technology, mediated through talibe like Samba Njay Bacily, to service its weapons and build its forts. Amadu forbade the use of European gunpowder in ceremonies. He kept records of firearms and owners, sought double-barrelled guns for his cavalry, and jumped at the proposition of obtaining artillery 14. For about two decades he received some 1,500 to 1,800 small arms per year through Bakel and Medine, and this enabled him to maintain a weapons differential over most of his foes. But only the loyalty of a surviving core of talibe, tuburus, and sofas can explain the endurance of his garrison state, however diminished and defensive, until the French conquest. Only a jihaad constructed around Umar's leadership, Fulɓe consciousness, and strong religious conviction could have weathered the storms of twelve years of offensive and three decades of defensive warfare.

Senegambia, by dint of its long contact with European traders, had thoroughly integrated firearms into its techniques of warfare. Distinctions between weapons had even passed into the language of proverb: in Khasso people said that ‘French guns are for dancing, while English guns are for war’ 15. Imported powder was consistently preferred over the local product 16. The favorite small arm was the double-barrelled musket. It solved some of the problem of shooting from horseback, and the Umarian cavalry proudly called themselves the ‘masters of the two barrels’ 17.

Further east it was possible to obtain a decisive advantage in firearms, as illustrated by the jihaadic army. In Karta the Umarians encountered Massassi forces with rusty guns. Segu imported weapons from Freetown, but probably did not have sufficient numbers to stem the second advance at Woitala. Hamdullahi still stressed a traditional cavalry. It was consequently devastated on the Thursday of Cayawal, when Umar forced his talibe to dismount and wait until the last moment to fire 18. It was not the absence of firearms so much as the inferior numbers, quality, and experience that weakened the foes of the jihaad.

A much more novel weapon was European artillery 19. Here the principal Senegambian experience was with guns mounted at forts such as Bakel and Dagana or on the European ships. The only local term which I have found to denote artillery is kanu, an obvious derivative of the French canon 20. Artillery had a revolutionary impact on West African warfare. They could batten walls with balls, lob explosive shells inside a fort, or flatten an advancing army with shrapnel. They provided the means to cut short the long sieges characteristic of much local warfare. A fortress like Somsom, the relay station in Bundu, was impregnable until Faidherbe's engineers rolled up their carriages. The French guarded such instruments of war jealously, forcing the jihaadists to capture them and train their own camel teams, carpenters, and smiths. When this was achieved, the Umarians brought devastating and mystifying power to bear on the Segovian fortresses. It is hard to conceive of victory at Woitala without the ‘rams of the Governor’, as the howitzers were called 21. In the domain of artillery, the Umarian advantage over its interior foes was absolute.

Superior firearms are obviously an incomplete explanation of the military success of the jihaad. Each foe was faced at a time of partial decline in prosperity and force. The riding skills of the talibe and the new mounts obtained in Karta and Segu played their part 22. Even more important were the superior unity, zeal, and perseverance which the Umarians displayed, often in the face of greater numbers. These qualities were especially critical at the siege of Tamba and the Kartan victories, where no artillery was available and the small arms were more evenly distributed. The sharpest reverses for the jihaad came when the indigenous inhabitants revolted and matched the zeal and cohesion of the invaders. When zeal was joined to a weapons blockade, as in Maasina, the result could be disaster.

The heavy casualties of the jihaadic years were the product of the lethal weapons used as well as the intense polarization of the struggle (Table 1). The consequences of the loss of so many persons, primarily able-bodied men, for the productive and reproductive work of societies in ‘west’ and ‘east’ alike were enormous. The agricultural cycle was disrupted for periods of three or more years. The consequences of this for nutrition and the amount of arable land are impossible to estimate. It is clear that vast quantities of grain and livestock were consumed by armies of all persuasions, mobilized at the expense of production, and that the increased use of European weapons helped sustain a pattern of violence that went far beyond the dates of the jihaad and the conventions of dry-season warfare. The whole escalating spiral encouraged people to migrate outside the theatre of combat or to offer themselves as pawns in exchange for security.

Table 9.1 — Approximate Casualties and Prisoners in Campaigns, 1852-6

| Umarians killed | Opponents killed | and taken prisoner | |

| Tamba | 200 | 1,200 | 500 |

| Karta | 7,200 | 9,500 | 6,730 |

| Senegambia | 6,700 | 3,300 | |

| Segu | 7,400 | 18,150 | 13,600 |

| Maasina | 30,000 | 39,700 | |

| Total | 51,500 | 71,850 | 20,830 |

Senegal and Mali have diametrically opposed memories of the jihaad 23. For the Senegalese, Umar and his talibe were heroes in the cause of Islam, the crusaders against the infidels. The Malians see their ancestors as defenders against Fuutanke invaders who used Islam as a cloak for their imperialism and personal greed. These contemporary images obviously correlate with the point of insertion into the jihaad. It is the task of this section to examine the crusaders, the ‘west’ from which they came, and the internal chronicles which recorded their mission. Section C looks at the defenders, the ‘east’ where they lived, and the sources which I have called external.

The Umarians fall into four main categories. Umar and the Tal family form the core, while the largely Fuutanke talibe constitute the next circle. These two groups initiated the jihaad, developed its ideology and made the regime endure. They were surrounded by wives and concubines, griots, artisans, and slaves who remain obscure in the sources. The third circle consists of tuburu, the submissive allies, followed by the sofas, the professional soldiers who enlisted once the jihaad gained momentum. The last two groups were not invaders, and they rarely internalized the cause to the point of becoming crusaders. While they became vital to the prosecution of the jihaad, they did not set its structure or tone, reap its main rewards, or sustain the jihaadic states until the French conquest.

The original Tal family lived in the villages of Halwar, Gede, and Donnay in the province of Toro. They consistently supported the jihaad and furnished a number of its leaders, but they fell largely in the category of talibe. By contrast the Tal who dominated the movement, furnished its dynasty, and inspired the internecine conflict of the late nineteenth century were principally the descendants of Umar 24. Their story begins with the return from the Holy Lands, when the pilgrim began to accumulate wives, concubines, and slaves in Hausaland. The story gathers momentum in Jegunko, Dingiray, and the jihaad, as Umar received additional gifts of women or contracted marriage alliances for political purposes 25. The result was a very large and young second generation, about one hundred strong, distinguished by their paternal ancestry but raised by their mothers (Table 2 below). The creation of such an instant dynasty was not unprecedented. Askiya Muhammad and the Fulɓe lineages of Hausaland expanded rapidly on the basis of political power, patrilineal descent, and multiple wives and concubines 26. But the Tal case is unusual in several ways. A person of modest origins is suddenly catapulted into prominence. He creates, in effect, a vast new lineage, conquers a vast area, and offers instant fiefdoms to his very young sons to administer 27.

Table 9. 2 — Known Wives and Concubines and Principal Sons of Umar Tal

| Wife or concubine | Origin | Date of marriage or tie | Sons, date of birth and date and place of death | Probable age order |

| Aisha Jallo | Sokoto | c. 1835 | Amadu Sheku (1836-98, on hijra) | 1 |

| Bambara woman | Karta | c. 1855 | Bassiru (c. 1856-20th century on hijra) | |

| Batuly Hausa | Northern Nigeria | 1820s-1830s | Hadi (1839-64, Degembere) | 5 |

| Muntaga (c. 1843-86, Nioro) | 10 | |||

| Amidu (c. 1860-late 1880s, Bandiagara?) | ||||

| Daba | Fuuta-Jalon Jalonke | late 1850s | Mubassiru (c. 1851-20th century, on hijra) | |

| Fadimata | Bobo | Lamin (c. 1842-?, Dingiray) | 8 | |

| Hassiru (c. 1855-20th century, ?) | ||||

| Fatima al-Madani? | N. Nigeria | |||

| Fatma Bile Kulibali | Karta | Najiru (c. 1860-20th century, Senegal) | ||

| Fatumata Batuly Sal | Fuuta-Jalon | |||

| Fulɓe woman | Bornu | c. 1832-5 | Daye (c. 1850-86, Nioro) | |

| Umahani (c. 1851-late nineteenth 19th century, Bandiagara) | ||||

| Muniru (c. 1852-c. 1892, Bandiagara) | ||||

| Fulɓe woman | Nuru (c. 1850-c. 1900, Nioro) | |||

| Fulɓe slave | Mahi (c. 1839-64, Degembere) | 6 | ||

| Jeynaba, Hausa slave | Northern Nigeria | Murtada (c. 1849-1922, Nioro) | ||

| Mariam Dem | Sokoto | c. 1835 | Habib (c. 1837-c. 1880, Segu prison) | 3 |

| Moktar (c. 1838-c. 1882, Segu prison) | 4 | |||

| Mariama Alfa Yusuf | F. Jalon Jalonke | late 1850s | ||

| Mariatu | Bornu | c. 1832-5 | Makki (c. 1836-64, Degembere) | 2 |

| Saidu (c. 1841-76, Dingiray) | 7 | |||

| Agibu (c. 1843-1907, Bandiagara) | 9 | |||

| Daha (c. 1847 - 86, Lambedu) |

Principal Sources: de Loppinot, ‘Souvenirs’; Mage, Voyage, passim; Segu 3/Cam; Soleillet, Voyage, passim.

Dingiray became the principal residence of the Tal family in 1849 and retained that distinction until Umar transferred some of his sons to Segu in 1860 and 1861. Even after that time the southern capital remained the home of most of his wives, concubines and younger children. In Umar's absence these women became the dominant influences in their children's lives. Their most consuming issue was succession to leadership in the jihaad. One faction emerged around Aisha and the claims of Amadu. Another coalesced around Makki, his brothers and the Bornu Fulɓe woman who took over the responsibilities of Mariatu upon her death. A third group revolved around Habib, Moktar, and their claims as grandchildren of Muhammad Bello.

The court also included slaves and free men from Hausaland. The slaves were given to Umar on his return from Mecca 28. They became highly trusted members of the early community and often received important assignments in the new state. Abdullay, who reputedly carried the baby Amadu in a calabash on the journey from Sokoto to Fuuta-Jalon, succeeded Alfa Uthman as commander of Murgula. Dandagura was put in charge of Farabugu, while Nyamu reigned at Kunjan in the early 1860s. The most conspicuous member of this contingent was Mustafa, Umar's barber and cook and later governor of Nioro. The most important of the free men was Abdullay Hausa or Abdullay Saidu Dem, a cousin of Uthman. He travelled between Dingiray and Nioro many times, brought Amadu and Makki to Markoya in 1860, and tackled many difficult missions 29. All of these Nigerians, together with the more influential women, helped make Hausa the intimate language of the court.

Umar attracted an enthusiastic following in Hamdullahi. These Masinanke Tijaniyya, who played such a critical role in the Umarian conquest and brief administration of the Middle Delta, remained at home. Only further research will clarify their motivations and the role of the Caliphate in their choices.

Fuuta-Jalonke followers had no problem of distance to surmount and they faced only occasional difficulties with their own regime. Many of them blended into the Dingiray community. Some of them taught the younger generation of Tal and remained in the town after the jihaad began. One prominent example of this group was Muhammad b. Ibrahim of Labe, adviser to Makki and author of the ‘Chronicle of Succession’ written in 1860. Other Fuutanke were important for their political constituencies and military talents. Alfa Uthman blazed the trail through the Mandinka corridor and brought his compatriots together in the Murgula ‘arm’. Mamadu Seydiyanke, a Bari from the royal house, played a leading role in the Segu and Maasina campaigns. Modi Mamadi Jan was the premier general of the early jihaad, and his sons Bubakar and Billo became trusted advisers of Amadu in Segu. The most influential man at Amadu's court was probably Mamadu Bobo, who counselled with his patron in the Hausa which they had both learned in Dingiray. Mage gained the impression that Bobo represented the old conservative tradition of the jihaad which prevented the young ruler from opening his regime to French influence 30.

Together the women, children, slaves, and talibe constituted the Dingiray community. They were united by their close attachment to the Shaikh, the fusion of Nigerian and Fuuta-Jalonke background, and a certain distance from the Fuuta-Toro contingents who came to dominate the ranks. The divisions between the Dingiray and Fuuta-Toro constituencies emerged in the campaigns in Tamba and Bambuk, at the beginning of the Segu campaign, and in the administration of Amadu Sheku. The divisions within the Dingiray community remained latent for some time. Umar contained them by installing his oldest son as his successor on several occasions between 1860 and 1863. He also sought to compensate for the youth and inexperience of his sons by assigning them to military and administrative duties. This experiment was a rough equivalent to the ribaat training which Uthman's descendants gained on the Sokoto frontier, but in the Umarian instance it was cut brutally short by the revolt of Maasina. Only Tijani among all of the second generation of Tal earned a reputation as a mujaahid and muraabit for Islam, and it was this new distinction which compensated for his lack of direct descent from the Shaikh.

From his capital at Segu Amadu appointed a number of his brothers to subordinate posts. He confirmed Habib in what was already de facto control of Dingiray. He told Agibu to supervise Segu in his absence from 1870 to 1874. In 1874, as he renewed his designation as Commander of the Faithful, Amadu put Bassiru at Konyakary, Muntaga at Nioro, Daye at Diala, and Nuru in Jafunu 31. For four years he was at the height of his power and reigned over virtually all of the conquered lands save Maasina. But the new title did not carry much weight with the second generation Tal or the Bambara. Habib and Moktar had already revolted and would not emerge alive from their Segovian prison. In the 1880s Muntaga made Nioro into an autonomous province and drew several brothers into the fold. Amadu could not tolerate such an excision from his domain, especially along the west-east artery. In 1885 he journeyed west, ended the revolt, and made Nioro his capital until the French conquest. Bandiagara became the scene of a later clash with Muniru, whom Amadu deposed in 1891, and subsequently with Agibu, whom Archinard installed in Amadu's place in 1893.

In the midst of these struggles the Commander of the Faithful called upon a highly esteemed scholar to support his case. Saidu An came from the Fulɓe family in the Middle Niger. He spent several decades at the Sokoto court, tutored some of Uthman's descendants in the Koran, and adopted the Tijaniyya affiliation during Shaikh Umar's passage. At a later time he made the pilgrimage, joined the Umarian jihaad and settled in Segu as a counsellor to Amadu. Although he never lived in Dingiray, Saidu had the Nigerian antecedents, the Hausa language and above all the knowledge of Sokoto history to make him a welcome member of the inner circle. It was in this capacity that he wrote a chronicle of the reigns of Muhammad Bello, Atiq, and Ali, and that Amadu called upon him for a fatwa or written consultation about the revolts of his brothers. Saidu responded with a well-documented opinion that Amadu was the clear successor to his father and was justified in any action which he might take against his rivals 32.

Despite the bitter struggles, Amadu was able to unite the surviving Umarian remnants in the face of the final French assault on the Western Sudan. As Archinard approached Bandiagara in 1893 with Agibu in tow, a small community of Tal and talibe, not unlike the community of Jegunko, Dingiray, or Kunjan in its intimacy, counselled the Commander of the Faithful not to fight but to incarnate their cause in flight to the east, where Muslims still reigned supreme. Amadu complied, took many of this inner circle with him, and spent the last five years of his life retreating from the French advance, drawing ever closer to Sokoto and the original home of his mother. His hijra began with the deliberations of the community and ended with his burial. It repeated the action of the recruits of 1858-9 and became part of the holy history of the movement 33. In contrast, the intervening years of strife, and indeed the whole period from 1864 to 1893, went essentially unrecorded. Despite the clear indications of succession and the fatwa of Saidu, many Umarians did not want to remember the plots, suicides and imprisonments within the holy family. In fact, the disarray in the second generation tarnished the memory of the jihaad and quickened the process by which new generations of Tijaniyya sought alternative connections to the order 34.

While the disciples from Fuuta-Jalon tended to blend into the Dingiray community, the much larger group of Senegambian followers remained distinct and often constituted a countervailing force. They included Soninke like Alfa Umar Kaba, who helped map out the Karta campaign; ‘Saint Louisians’ who played a critical role in establishing trade connections, building forts, and servicing artillery; and the people of Bundu, who furnished such a large proportion of their country to wage the holy war. The largest, most important and most sustained contribution came from Fuuta-Toro. Without it the jihaad would not have gone beyond Tamba nor achieved its formulation in chronicle and poetry. While Umar gave the movement its basic shape, it was the talibe of the middle valley who transformed his inspiration into an ideology.

Mage's principal informants in Segu came from Fuuta-Toro. The writer of the anonymous Fulfulde account of the early jihaad came from there, and the authors of the early Arabic and anonymous Segu chronicles probably did too. Two Fuutanke compiled the most complete narratives of the jihaad: Abdullay Ali, the lower-level secretary who became an important counsellor to Tijani, and Mamadu Aliyu Cam, the modest follower from the Hayre region who hammered out his story at the Segu court. What all of these men had in common was an insertion into the movement at the point where it led directly to jihaad. They enlisted between the 1847 journey and the 1852 declaration. They did not have first-hand knowledge of the return from Mecca or the teaching in Jegunko, and they formed part of the faction pressing for more militant action. In the devastating vacuum created by Umar's death, it was they who persisted in writing accounts for future generations.

The clearest expression of the talibé ideal and ideology of the jihaad comes from these authors, and especially from Cam. The first act of the talibé was renunciation. He rejected the society of his birth and any loyalties which might compete with the new mission. Cam wrote frequently about 'people who had severed ties to mother and father, who had chosen Paradise 35. Alfa Umar Baila voiced the same ideal as he tried to bring Alfa Uthman back into the fold during the Segu campaign 36.

The rejection of ‘home’ meant attachment to the Shaikh. This took the form of bai'a, the oath of allegiance. The talibe voluntary and meritorious act was distinguished from the surrender of ‘infidels’ by the addition of more intense language: ‘covenant’, ‘allegiance to death’, or ‘allegiance of active consent’. The attachment was made manifest in courage and competence in battle. The talibé, with his mount and double-barrelled gun, pressed constantly against the enemy and followed every command of his leader. He was the crusading knight of the Middle Ages.

Rejection and attachment in turn yielded a new community, the jama'a of Arabic, the fedde or age-grade of Fulfulde. In the words of Cam,

Obedient to the Shaikh, they do no work save his work;Should the talibé die fighting, he became a martyr who could expect to go immediately to heaven. He had the equivalent of a Papal indulgence 38.

Whatever he prescribes, they will not resist it.

Loving one another, aiding one another in everything, Rising early and giving one another gifts, they are not idle

The age-grade of God is there, educated to the preparation

Necessary for God and the Prophet, who will not be

anxious for them [on the Day of Judgment] 37.

The chronicles were intended not so much to record what happened as to transmit the heritage of sacrifice, community, and victory to new generations. The ideals diverge significantly from Fulɓe epic literature, which celebrates the autonomy and individual bravery of the warrior chief 39. The tone was more intense than the literature associated with the earlier Fulɓe jihaads. While the talibé ideology was rarely fulfilled and never entirely separated from material booty, it did motivate the Muslims of the ‘west’ and represent the culmination of the Fulɓe sense of election.

Nowhere was this more emphatically true than in Fuuta-Toro. It was Fuuta that gave its names to the first three regiments of the army. It was Fuuta that integrated the Umarian movement into its domestic politics. The position of Almamy was reduced in importance, while the hijra to ‘Nioro’ became a holy act, a substitute pilgrimage and a means of acquiring wealth and credentials for holding office back home 40.

The pattern of Fuutanke support varied considerably in time, space, and motivation. Until 1854 Umar could afford to recruit selectively across the whole spectrum of free classes. Persons from modest background volunteered and acquired positions of relative importance in the Dingiray community. With the expansion of scale for the war against Karta, the Shaikh had to recruit through local structures of patronage. His envoys addressed themselves to village and regional leaders, assured them that traditional hierarchies would be respected, gave gifts of slaves, and promised additional rewards. Each chief was expected to bring his entourage and fight with his unit in the campaign 41. The capture of the Farbanna asylum, like the refusal to endorse the Hubbu revolt, was an important signal that the jihaad would not overturn the social order.

It was none the less true that emigration offered a particular opportunity for younger sons, weaker families and fugitives from authority. Mamadu Hamat, the alleged assassin, fled for fear his fellows would hand him over to the French. His family, the junior branch of the Wan lineage, furnished a number of distinguished talibe including Alfa Umar Baila and Baidy Abdul Kader, a secretary to Umar. In the senior branch of the same lineage, Ifra Sire left after his cousin, Mamadu Biran, poisoned Ifra's father and excluded the family from power at the village and provincial level 42. For other Fuutanke, the jihaad meant military experience and material booty before establishing themselves at home. This pattern was especially frequent before the massive recruitment of 1858-9 and during the lull between that recruitment and French expansion in the 1880s.

The secondary sources often portray Fuutanke support as highly biased in favour of Toro. In this view the eastern and especially the central provinces resisted and even betrayed the call. Such a judgement is highly misleading. It is based primarily on the 1858-9 campaign, on the hesitation expressed at Horndolde and Hoore-Fonde, and on the actions of individuals like Abdul Bokar. Only the entire valley could have produced the massive column which made its way to Nioro, and Eastern Fuuta provided as large a contribution as the western provinces. The leaders of Bosseya and the centre were not ‘betraying’ Umar by organizing resistance, nor were they just defending their class interests 43. They had moral and familial investments in the integrity of their country.

The stereotypes about Fuutanke resistance also obscure the very careful recruitment pattern which Umar crafted and the surprisingly representative participation which he obtained over the years. The Shaikh sent people of high status and good access to address particular constituencies. The mission of September 1854 is a good example 44. It included one man from a village of the Ngenar waterfront, someone from a prestigious lineage in the Hayre cluster, and someone from the ruling family of Toro. Its leader was Alfa Umar Baila, cousin of ‘assassin’ Mamadu and Almamy Mamadu and uniquely placed to transform the frustration at Podor into participation in the jihaad. The team was startlingly successful: the column which made its way to Farbanna was remarkable both for the number and status of its recruits.

It is none the less true that the traditional cleavages of Fuuta penetrated through the recruitment, the war, and relations in the successor states. Members of the central Fuuta oligarchy resented the rise of the obscure cleric and his Toronke followers. Umar saw the regime of electors and tax fiefs as a betrayal of the goals of Sulaiman Bal and Almamy Abdul, and he selected many of his advisers from those who shared his views. The tension was evident in 1858-9. The opposition came from people like Almamy Mamadu and Eliman Rinjaw Falil. Guards stayed with the Shaikh in Hoore-Fonde, while Toro contingents protected the grain that had been stockpiled there. The tension persisted in the ‘east’ whenever Umar gave preferential treatment to the Toro or jomfutung regiment, or named a Toronke to command the whole army. The Shaikh succeeded in containing the cleavage, thanks particularly to talibe from the leading Fuutanke lineages who had been formed in the early days at Dingiray. Foremost among these was the indispensable Alfa Umar Baila 45.

The operation of the cleavages is best illustrated in the relations between the Kan lineage of Bosseya and the Tal 46. Ali Dundu Kan, participant in the plot against Almamy Abdul and kingmaker in the early nineteenth century, received a number of tax fiefs in Toro, including the village of Halwar. His son Bokar Ali became a prominent member of the electoral council in the 1840s, married the daughter of a wealthy merchant in Podor, and collected taxes in the villages nearby. Bokar subsequently made the journey to Farbanna and stayed for the Karta campaign. He soon became a vocal critic of military strategy and the failure to distribute booty equitably. He none the less stayed with the forces until 1857 or 1858.

Meanwhile his son Abdul joined a column sent to support the siege of Medine. En route the troops engaged a contingent loyal to Bokar Sada. They were on the verge of victory when French-equipped reinforcements arrived, whereupon Abdul persuaded the men to continue on to Khasso. They arrived too late to affect the outcome of the siege, but in time for the Shaikh to rebuke Abdul for abandoning the fight. The Bosseya leader promptly abandoned the jihaad, encouraged others to do the same and forced Umar to post guards to prevent additional desertion 47.

Abdul Bokar returned home before the 1858-9 recruitment. It was there that he received the Shaikh's gift of slaves, designed to induce him and his entourage to reconsider. He refused the solicitation and organized the most effective resistance to recruitment during that turbulent year. Meanwhile his father had returned to Fuuta. Bokar and his wife were forced to join the column moving to the east in the spring of 1859. When Bokar died about a year later, Umar refused to offer a blessing because of the elector's use of tobacco. The Bosseya contingent threatened to desert and forced the Shaikh to pray 48. The reluctant blessing and the kidnapping helped ensure Abdul's consistent opposition to the jihaad and hijra over the next three decades.

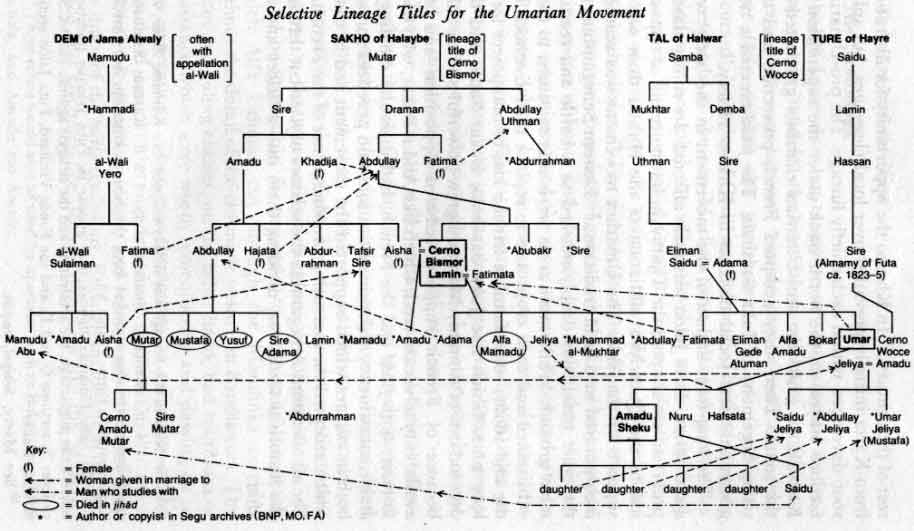

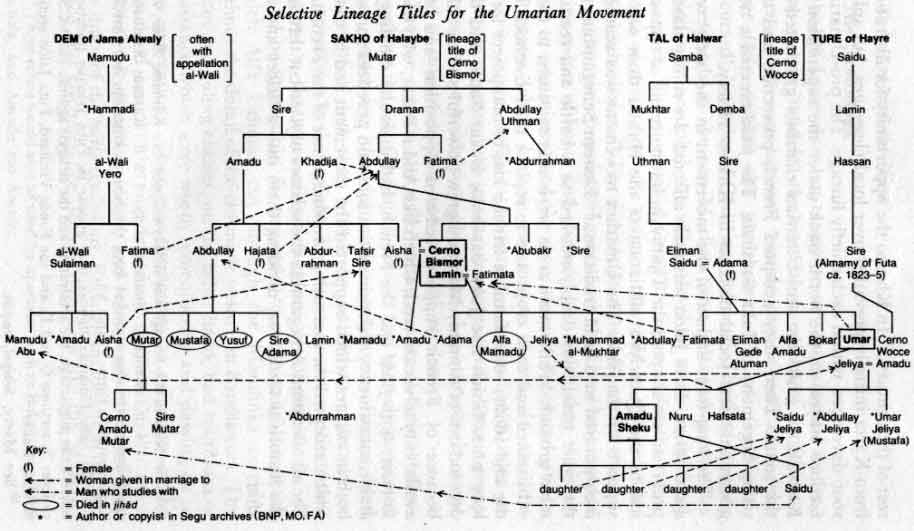

The same cleavages operated in Segu in the late nineteenth century 49. The talibe from the central provinces resented Amadu's reliance on the Toro regiment and its leaders, as well as the privileged position of the Dingiray community and some sofas. The ideology of talibé dedication and equality made matters worse: having given up so much to join the jihaad, why should Central Fuuta participants not have direct access to the palace, nor receive their share of weapons and booty? Amadu could not, unlike his father, recruit replacements for the central Fuutanke lost in the Maasina campaign. He came increasingly to rely upon his more natural and renewable constituency in the western region. His secretariat came principally from the Ture of Hayre and the Sakho of Halaybe: kinsmen, in-laws, and allies since Umar's childhood. The Sal of Gede, the Cam of Halwar, the Dem of Jama Alwali, and other lineages could be counted on to support his cause (see Table 3) 50.

Selective Lineage Titles for the Umarian Movement

Recruitment in other parts of the ‘west’ tended to follow the basic fault lines of the societies. In Gajaga the villages of Goy embraced the cause and joined in the destruction of Makhana, their traditional enemy and ally of the Bambara. In Bundu it was the weaker Kussan branch of the ruling family which cast its lot with the jihaad. Some of the Bulebane house defected, and it was among their number that Faidherbe found Bokar Sada. The Bulebane Sy became the effective dynasty for the rest of the century 51. In Khasso the opportunity for liberation from Karta initially prevailed over local cleavages, but splits soon developed within each chiefly lineage. The pro-Umarian factions stayed on the north bank under the supervision of Konyakary, while the anti-Umarian elements gravitated to the south. There they accepted French protection and the rising hegemony of Juka Sambala. The jihaad created a new geographic and social division in Khasso society.

The long-term impact of the movement in the ‘west’ was quite varied. Fuuta-Jalon was little affected. Its ruling classes progressively adopted the Tijaniyya, but more out of opposition to the Qadiriyya affiliation of the Hubbu than out of support for the jihaad. The Umarian movement was scarcely incorporated into local traditions 52. Eastern Senegambia, on the other hand, was deeply marked as a battle and recruitment ground. While most areas were able to return to their subsistence and cash crops and to replace their livestock by the mid-1860s, some families felt the loss of manpower for a long time. Chiefs like Juka Sambala, Bokar Sada, and the descendants of Almamy Mamadu grew powerful and wealthy because of French support, reduced opposition and the availability of vacant land. Chiefs like Abdul Bokar, who tried to resist both jihaad and the French, had difficulty creating a stable constituency. Islamic institutions and practices spread, both in villages which supported the movement and in those which accepted the increasing preponderance of the French 53. For all of eastern Senegambia the scissors of jihaad cut through the historical traditions, dividing them into a before and an after.

Although Islam does not recognize any fundamental distinctions among ‘infidels’, the internal chronicles of the jihaad do mark a difference between ‘simple pagans’ and those who more fully deserve the punishment of God: ‘betrayers’, ‘accursed’, ‘enemies of God’, and ‘tyrants’. The first category corresponds to the non-Muslims who belonged to stateless societies or occupied the village level of more hierarchical structures. The more vivid terms are reserved for the ruling classes of the states who resisted the jihaad or revolted after initial submission 54. The distinction is useful here for separating the sparsely populated areas which the Umarians invaded for purposes of booty and passage, but which they made no effort to administer, and the more densely populated, stratified states which became the targets of war. In the first category it was sufficient to establish a fort like Kunjan or Murgula to protect the vital trade routes. In the second group of areas the crusaders sought to run, however poorly, some kind of administration and political economy.

The two regions also differ in the quality of their recollection about the war. The small villages and sparsely populated areas remember the destruction, migration, famine, and enslavement, but they attach no narrative, sequence, or interpretation to their plight. The events do not constitute their history, in the sense of initiating any significant action. It would be impossible, for example, to reconstruct the swath which Alfa Uthman cut through the Mandinka corridor without the detail of the chronicle written in Bandiagara. The states and ruling classes, on the other hand, had traditions of resistance which were worth remembering and passing on to new generations. They saw themselves as defenders of the homeland against the invaders from the ‘west’.

Their recollections, ideals, and stereotypes obviously lack the unity of the talibé traditions. Each group fought in its own place and circumstance. Ruling dynasties like the Massassi had difficulty mobilizing their constituencies, or even in presenting a united front among themselves. Some common themes none the less run through the traditions. The defenders imbibed various forms of alcohol, let their hair grow long, and consumed tobacco. They enjoyed public dances, a rich variety of musical instruments and freer relations between men and women. At the appointed times they brought out their household and national cult symbols, not to worship as ‘fetishes’ in a polytheistic ‘association’ with God, but to express gratitude, entreat blessing, or instil pride. It is striking that the defenders often identified the same symbols of distinction as the crusaders, and then interpreted the distinction in a very different way 55. Mari Sire, in his encounter with Nuru Tal, objected to the rosary, the kidnapping of women, and the arrogance of the Umarians. Others made fun of the ‘shaved heads which touched the dirt and forced their bottoms up in the air’, or the noses which were held so high that the rain came in and produced constant colds 56. The defenders expressed themselves more bitterly when they remembered the power behind the symbols. The French officer Galliéni encountered a Bambara chief in the eastern marches of Karta in 1880. The man greeted him icily and said:

When Al-Hajj Umar came to our country, he spoke to us in the same manner as you. He overwhelmed us with sweet words and gifts, saying that we were weak and he wanted to protect us. Soon afterwards we became the slaves of Segu. Our women no longer belonged to us and our villages were destroyed. We were forced to take refuge in the mountains. Since then we have taken up arms ... and we wage war against the talibe of Amadu 57.

Both the traditions and the reality of resistance were most consistently maintained by those who stood to lose the most, the displaced dynasties. Balobbo and Amadu Abdul, descendants of the founder of the Maasina Caliphate , led part of the struggle against Tijani. Kege Mari, assassin of Torokoro Mari, instigated some of the early revolts in the Middle Niger, while various Massassi tried their hand against Nioro. The most persistent was Dama Kulibali, son of the last strong ruler of Bambara Karta (see Chapter 5, Table 1) 58. While his brother Mari Sire established himself in exile in the Mandinka corridor, Dama sought out the support of the French. He lived in a number of villages in Gajaga and Gidimaka, with a large following of relatives and sofas. He soon created a microcosm of the old Bambara court, complete with dances, griots, and remembrances of things past. He raided for slaves, put them to work in peanut fields, and grew quite wealthy in exile. But he continued to plan for his return to the land of his ancestors. In the early 1870s he seized the opportunity provided by Amadu's struggle with his brothers to establish a village called ‘New Gemu’, in memory of a former Massassi capital. Amadu's counter-attack drove him back to Gajaga, but Dama then supported the French advance to the Niger and kept up a running correspondence with the Commandant Supérieur about the liberation of his homeland. His opportunity finally came in the early 1890s, when Archinard chased Amadu from Nioro and approved the reinstallation of Dama and his sons. During this period the old man had a major impact on the traditions which the French administrators formulated about the Umarian domination of Karta.

The Jawara offer an interesting variation on the opposition of the Kulibali. They made an argument about the terms of incorporation, not ultimate sovereignty. They had come to accept the overrule of the Massassi. When the dynasty made excessive demands in the 1840s, they revolted and later embraced the jihaad as tuburu. It was only in late 1855, when Umar presided over the distribution of booty and awarded the Jawara a smaller share than the talibe, that they went into retreat and rebellion. Karunka, an intrepid warrior, took over the campaign from the traditional chiefs. He became the defender of the object which symbolized the long tradition of autonomy of the people: a sword which the founder of the state of Jara had allegedly received from a holy man of Mecca. The conflict soon turned bitter, at the ‘day of those seated in the sun’. Karunka became a much more obsessed foe of the jihaad than Dama ever was. Alfa Uthman's drive through the Mandinka corridor deprived him of one refuge, while Umar's push to the east flushed him out of south-eastern Karta, but it was only in an unguarded moment in 1860 that a contingent of talibe caught Karunka and killed him. The Jawara continued the struggle by joining Bina Ali's defence and harassing the Fuutanke at every occasion. Finally Umar, as he collected his legions to fight against Hamdullahi, made peace, presumably on more favourable terms than he had been willing to accord years before: ‘The Jawara cut their hair which they had grown excessively long [during the long years of rebellion] and converted to Islam. Al-Hajj received them magnificently [in Segu] and overwhelmed them with gifts.’ 59. Conversion for the Jawara was not individual renunciation nor attachment to the Shaikh, but gaining recognition and status as a group. In fact, conversion in all of the ‘eastern’ societies was loaded with political and social implications, from the time of Jeli Musa's first steps in Tamba.

A very different kind of opposition and documentation comes from certain learned circles. These scholars, however motivated by the desire to protect commercial or ethnic interests, formulated their arguments in terms of Islamic law and consensus. The most general position emerged from the experience of corruption brought on by war and politics. The Jakhanke of Tuba rejected Umar's invitation on this basis. Ahmad al-Bekkay wrote the Shaikh about how the jihaad would lead to kingship and oppression 60. A more specific criticism was levelled at the violence of warfare, particularly during the repression of the revolts in Karta. Alfa Umar Kaba protested the execution of the Jawara hostages, while staying within the ranks. Bokar Sada objected to the execution of his Massassi kinsmen, escaped from the crusaders and forged his alliance with the French. The violence theme could expand into an accusation that the movement was losing its focus on idolatry and was instead becoming an occasion for settling scores, waging civil war, and grabbing booty. This was the argument of fitna, ‘trouble’ or ‘sedition’, and it was invoked by Amadu III and the Kunta. The Kunta, in the person of al-Bekkay, carried this position further by declaring Umar an impostor and evil-doer in early 1863 in the jihaad against ‘false’ jihaad.

The critiques had little direct impact as long as Umar was fighting against what the scholars accepted as ‘paganism’. All the themes were articulated many times by Bekkay, who saw the threat which the holy war and Tijaniyya allegiance posed to Kunta interests 61. Faidherbe and the Muslim community of St Louis used the same positions, often borrowed word for word, in the propaganda war which they waged in the late 1850s 62. Their efforts probably had some impact on Senegambian opinion in the wake of the massive emigration of 1859. But it was ultimately only the campaign in Maasina which fused the Islamic arguments with indigenous nationalism to create a successful revolt.

In this study I have used a number of extant accounts of opposition to balance the internal chronicles and create as full a narrative of the jihaad as possible. A systematic collection of external traditions from local libraries and elders should be a high research priority, and it would undoubtedly bring many modifications to this study. It would almost certainly not, however, challenge the basic conclusion which I wish to draw here: that the indigenous traditions are primarily devoted to some form of resistance and not to accommodation to the rule of the Fuutanke. The absence of a rationale for accommodation reflects the very limited assent which the inhabitants of the 'east' gave to the Umarian regime. It is the complement to the argument I have been making about the internal chronicles: that they deal with conquest and destruction, not with the establishment and administration of an Islamic state. The ideal of the talibé holds up valour and piety, but not the qualities of a successful ruler. The symmetry between the structure of the jihaad, on the one hand, and the external and internal sources, on the other, is virtually complete.

The disinterest of the narratives in administration goes back to Umar, his talibe and the jihaad which they fashioned. This is not to deny that the area of conquest was too vast, the speed of conquest too rapid, or the younger Tal too inexperienced, but rather to see these elements as the consequence of the structure. The Shaikh never created the context for writing treatises on government, as Uthman did soon after the beginning of the Gobir movement. After the conquest of Tamba Umar committed himself to a campaign of much larger scale, and he rarely slowed the pace sufficiently to consolidate control in any region. When he recreated some of the intimacy of earlier days in the wake of the Medine disaster, it was for the purpose of sustaining morale and launching the second phase of conquest. When he emerged temporarily triumphant in Maasina, he planned a kind of imperial militia to keep the courts in line. The orientation of the chronicles reinforce the argument that Umar, and those who supported him, saw themselves as destroyers of ‘paganism’, not the architects of a new Islamic state 63.

This does not mean that the movement made no effort to establish new institutions. In the four major areas of conquest, as distinguished from the Mandinka corridor, the new injunctions on conduct were imposed, primarily on members of the former ruling classes and inhabitants of the larger towns. Mosques, schools and courts were established, although these operated largely for the crusader communities. Each new palace contained a treasury, with the booty confiscated from the previous regime and the proceeds of taxation, as well as a chancery, which managed incoming and outgoing correspondence and used the new Umarian seals 64. Systems for levying taxes and tariffs were established. They exempted talibe and consequently bore down more heavily on the indigenous subjects. The confiscation of property was sufficiently common to evoke complaint 65. In each of the four areas the Umarians probably had somewhat more generous terms of incorporation in mind at conquest, but they scrapped these plans after repressing the indigenous revolts 66.

The cycle of revolt and repression also stimulated the call for new colonization from the ‘west’. New settlers were more likely to support the ideals of the jihaad; the ruler could use them to prod the more settled talibe to act. When the crusaders were sufficiently numerous, they moved out of the main garrisons, settled on the land, and took wives, concubines, and slaves to work their fields and serve in their homes. This in turn increased security, extended the reach of the administration and caused some shift in the local demographic equation. Just as the Tal had expanded dramatically in one generation, the talibe could, under certain conditions of privilege and patrilineal succession, become numerically as well as politically dominant in a short time.

In so far as an Umarian model of state formation existed, it was based on colonization from west to east: an immigrant group settled on the land, administered the state, waged war, brought in new slaves, and exploited the productive capacities of the indigenous inhabitants. While the new ruling class might express themselves in the language of Islamic law, they did not operate in ways qualitatively different from the warrior elites which preceded them. They had the additional stigma of being perceived as foreign.

None the less, the colonization model worked fairly well in the zones contiguous to the ‘west’ which were conquered during the first phase of the jihaad. Tamba was progressively transformed by the influx of Fuuta-Jalon migrants in the late nineteenth century. Immigration also transformed parts of western and north-western Karta. Here, in addition to proximity to the ‘west’, it was the intense recruitment organized by Amadu during his periods of residence in Nioro which created the pattern. Land was available to land-hungry citizens from the Senegal River valley. This large infusion of people laid the basis for the only full implementation of Islamic law which the successor states experienced: the regime which Amadu ran from Nioro between 1885 and 1891.

Maasina and Segu show a very different pattern. In Bandiagara Tijani had to reconstruct a regime from scratch. He took his main counsel from the surviving talibe, but he relied heavily on Dogon, Tombo, and indigenous Fulɓe for provincial administration, running courts and teaching schools, as well as supplying the bulk of the army. Segu was closer to the Karta and Tamba pattern, but the talibe numbered only 4,000 in the 1860s and did not expand very much in later decades. They remained confined to the capital or nearby garrisons. Under these conditions the distinctions between talibé, tuburu, and sofa lost some of their economic and political significance. Wulibo, the leader of the Fulɓe of Karta who were brought to Segu, never sought the rank of talibé, but he married a Senegambian immigrant and acquired responsibility over slaves, grain distribution, and tax collection. Mage called him the second most powerful person at the court 67. Arsec, a sofa from Segu, became Amadu's barber, cook, executioner, and a very influential counsellor at the palace 68.

Amadu sought consistently to bring talibe, tuburus, and sofas from Karta to strengthen his position. This policy and the need for firearms made the west-east connection critical to his survival. It was his inability to control the connection which brought him to Nioro on two occasions. Each of these displacements resembled the royal mahalla of nineteenth century Morocco: the ruler marched between capitals with a large armed party to restore obedience, collect taxes, and conscript soldiers 69. In Amadu's case the army did not always ensure protection: in 1884-5 he had to spend many months in Nyamina before the way was clear to the west.

The successor states did not encourage conversion to their faith. As in the Crusader kingdoms of Palestine and Syria, conversion could reduce the tax base and cloud the distinction between ruler and subject 70. None the less, Islam did spread to some extent in the areas of significant administration and colonization. In Tamba and parts of Karta, the large numbers of practising Muslim settlers and the strength of the Islamic institutions influenced the indigenous inhabitants. Some of the latter, like the Soninke of the Kolombine valley, already had predilections for Islam, and the Umarian regime encouraged them further. The Islamic influence of the jihaad wanes rapidly as one moves into eastern Karta, Segu, and Maasina. A close reading of Paul Marty's survey of the French Soudan in the early twentieth century shows the faith spreading as an alternative to European allegiance but through the agency of indigenous Soninke, Fulɓe, and Moorish clerics 71. In fact, the Umarian conquest probably delayed the expansion of Islam because it temporarily associated the Muslim faith with an imperial thrust and intensified loyalty to indigenous institutions.

The fortunes of the economy of the Middle Niger under the jihaad are nicely captured in a story told in the Segovian traditions 72. Umar, upon arriving in the luxurious palace of Bina Ali, finds four important symbols of local prosperity: a hen incubating her eggs, a stalk of fresh millet, a calabash of fresh milk, and a lamp which remained lit night and day. Each had been in existence for 333 years. Umar kills the hen and takes the eggs, cuts the millet stalk, pours out the milk, and extinguishes the lamp. Later Bina Ali informs him of the gravity of his actions. The cohesion of the Segu population would be lost because of the killing of the hen. Famine would come because the millet had been cut, and cattle epidemics would ensue since the milk had been poured out. Segu would cease to be the beacon of the region since the lamp had been extinguished. The informants gain a last measure of satisfaction by linking the four symbols with the ‘idols’ which Umar so conspicuously smashed in Hamdullahi. This is their way of saying that the Bambara deities got their revenge on a movement which put the prosecution of jihaad ahead of the economic verities of the Middle Niger. The message could be extended to most of the area conquered by the Umarians.

The short-term consequences of the jihaad were immense. They have been discussed in Section A. Over the long term the political economy of the crusader state depended on north-south integration across the different ecological zones. In the Karta-Mandinka sphere the Umarians were fairly successful. They had reasonably good relations with the desert-side traders and thereby maintained the commerce in salt 73. The forts of Murgula and Kunjan retained access to the gold, kola nuts, and slaves of the south. Small contingents of armed guards were usually adequate to protect the caravans 74. This section of the state also had the obvious advantage of proximity to the ‘west’, its firearms and other imports.

In the Middle Niger the crusaders failed. Maasina and Segu were cut off from each other. This in turn deprived Segu of access to Timbuktu and the central caravan route across the Sahara, and it compromised the fortunes of Sinsani, the emporium which lay close to the boundary between the two states. The Maasina wars of the late nineteenth century were much more bitter than the skirmishes of Caliph and Fama in an earlier day. They produced a continuous flow of refugees, pressure for food, and predatory warlords 75.

The Fuutanke were never able to restore the cycle of prosperity of the Segu heartland. They did not know how to organize the farming themselves, received minimal cooperation from the Bambara peasants, and were not able to ensure a steady supply of slaves. Instead of allowing Marka merchants the conventional conditions of autonomy, they taxed the trade heavily, confiscated property, and interfered in the choice of chiefs. Nyamina stayed within the state, but shrank in significance. Sinsani gained its independence, but at the cost of its former prosperity.

The small contingent of talibe in Segu could not control the government, army, and economy, nor could they infuse the regime with the ideals of the jihaad. They were divided by loyalties to Dingiray and Fuuta-Toro, or to the western and central provinces of Fuuta, and by common resentment against the influential sofas and tuburus. Many wanted to leave. Nyamina consequently became not only the means of trade with the west and south but also the gate which prevented flight. When the talibé problems were complicated by warfare on the left bank of the Niger, Amadu was completely isolated from the structure which had been the life-blood of the movement. He could not maintain the weapons superiority, he could not bring in new settlers to challenge the disenchanted. The Umarian state of Segu failed to fulfil either the older pattern of political economy of the Middle Niger or the newer model based on colonization and supply from the west.